A few years ago, Shelli R Johannes’s young daughter announced that she no longer wanted to attend a science summer camp. She had been the only girl there the previous year and had concluded that science must just be for boys. “It was so sad because she was a very science-minded girl,” says Johannes. “She wanted to be a vet, so it was surprising.”

Johannes realised that her daughter’s experience must be one shared by thousands of other girls. She confided in her friend and fellow Young Adult author, Kimberly Derting, and the pair decided to write a children’s book, at the heart of which would be a girl who loves science.

“We don’t tend to write picture books, but we felt it was very important to send out the message that girls need to be studying science,” says Johannes. “And that science is fun, not just a subject at school […] There are so many things you can grow. Or you can cook and that’s chemistry. Science is all around you.”

Inside the book

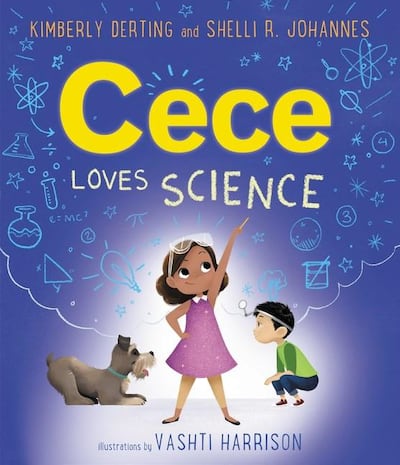

The result of this collaboration is Cece Loves Science, a delightful picture book with illustrations by Vashti Harrison, in which an inquisitive young girl called Cece seeks out answers to the many questions she has buzzing about in her head: "Do fish get thirsty?" "Is a bear ticklish?" and, the key conundrum around which the book's plot orbits, "Do dogs eat vegetables?"

With her best friend Isaac, Cece carries out a series of experiments – "What if we just mix up vegetables with his kibble?" – to find out whether or not her dog, Einstein, will ever polish off his greens. I'd hate to spoil the ending, but suffice it to say that science emerges as the star of the show. "Science isn't just about asking questions," Derting and Johannes write on the final page of Cece Loves Science. "Real scientists have fun finding answers, too."

For all the jolliness, though, Cece Loves Science champions real scientific rigour. Cece and Isaac use variables in their experiments and produce worksheets on which they interpret data. There is also a glossary and a list of facts at the end of the book with information about famous scientists. "We needed a science experiment that wasn't just from a text book, but which met the education standards," says Johannes.

Why girls turn away from science

Cece Loves Science could not have arrived at a more critical moment. The overwhelming majority of jobs in science, technology, engineering and mathematics, known as Stem subjects, are still taken by men. In 2014, for example, women earned fewer than 20 per cent of doctorates in engineering from US universities, while a recent Unesco report found that, globally, just 28.8 per cent of researchers are women.

These statistics appear to confirm what Derting and Johannes suspected: girls are being turned away from science, often at a young age. The reasons for this are complex, but the ways in which society defines the things girls should be interested in is undoubtedly a major factor. "In the US, girls are given books like Fancy Nancy and Pinkalicious," says Johannes, "while boys are getting pushed dinosaurs and trucks and encouraged to be astronauts. It's about saying that you can be fancy, pink and smart."

There is a problem with confidence in young girls, too. “My youngest daughter would say: ‘I’m no good at science or mathematics,’ and I would say, ‘I don’t think that’s true, I think you’re telling yourself that’s true,’” says Derting. “There are girls who sabotage themselves.”

What's next for the duo

Derting and Johannes, who are in the UAE at the invitation of the US embassy for the Abu Dhabi International Book Fair, have been rewarded for their part in the fight back with a six-book deal from HarperCollins. "Our editor had a similar experience with her daughter who loved science and then went through a period of thinking it wasn't for her," says Johannes. "That's why this book resonated with her." The next instalment of the series, Cece Loves Science and Adventure, is due out in June.

Both Derting and Johannes are successful authors in their own right. Has it been problematic writing as a team? “It’s like a marriage,” says Johannes. “There are moments when you click and moments when you disagree and have to compromise.” Derting mimes hanging up the phone and the pair both start laughing. “But no, we love it,” continues Johannes. “We have so much fun together.”

And what about Johannes's daughter – has she rediscovered her love for science? "She joined a veterinary programme for teenagers this summer," Johannes tells me. "They only chose 50 students and she got in." Proof, then, that young minds can be changed and changed again – although Cece Loves Science should help to ensure children no longer need much persuading to ask, "How?", "Why?", "When?" and "What if?".

Cece Loves Science is out now, published by HarperCollins