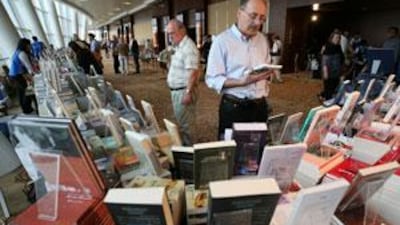

Happy crowds thronged Dubai's Festival City Intercontinental hotel. Signing queues snaked across the conference centre lobby; the book stands did a steady trade. Authors and media personalities shuffled about in knots, conversing noisily. Here's Anthony Horowitz telling Penny Vincenzi about an enormous car crash that was staged for one of his television series. Here are the Hislops, Ian and Victoria, sweetly inseparable for the duration of the festival. For the fannish eavesdropper, it was heaven. And indeed, to the eye, the first Emirates Airline International Festival of Literature looked to have been rather a triumph all round. Ah, but here's a conundrum. What does success mean in the world of books?

In the EAIFL's opening debate the Moroccan poet Mohammed Bennis said something moving. The discussion was of the role that prizes now played in book culture, and the panel was made up, as you might expect, of writers with a lot of trophies to boast about. This they did: Rachel Billington trilled: "I think I've given more awards to more people than anyone else in the world," before running us through her illustrious CV as a Man Booker and Writer's Circle judge. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, writer of the excellent Half of a Yellow Sun and recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship (the genius grant, as it is sometimes called) pantomimed dismay at the fact that, in Nigeria, she is popularly known as "the prize-winner". The Pulitzer prize-winner Frank McCourt couldn't stop saying "Pulitzer Prize-winner Frank McCourt". Asked about his own crowded mantelpiece, though, Bennis said: "Translation into another language is a prize in itself? maybe the biggest prize I can think of." It's a noble thought - that passionate attention should trump megabucks and baubles - and it speaks to some of the contrasts of culture and approach that the festival brought fascinatingly into focus.

On the one hand, its programme was crammed with highly bankable commercial writers - authors who are both concertedly populist and deservedly popular. Karin Slaughter, Terry Brooks, Wilbur Smith and Penny Vincenzi all write by the yard, sell by the shipping container and are only too happy to tell you how to do the same. The fantasy novelist Terry Brooks, for example, warns of the dangers of doing research if you want to be prolific. "I always hesitate to tell people that because they think, 'Oh brother, what a philistine'," he said wryly, before offering the cautionary example of his friend, the slow-moving author of The Clan of the Cavebear, Jean Auel: "When we last saw her she was getting ready to do her fourth book, after all these years, her fifth book, whichever it was. She said it took her so long because she got into the library and she couldn't get out." He laughed. "Sounds like the ninth circle of hell to me." And though Karin Slaughter's gritty Georgia-based thrillers are very thoroughly researched, that doesn't appear to slow her down. Indeed, in a Q&A with the tireless literary interviewer Paul Blezard, she even evinced a certain professional exasperation with the more precious sort of snail's-pace literary writer. Asked why she thought crime novelists got passed over for big awards, she said book prizes "were like welfare for people who write very slowly". She drafted her (excellent) novel Blindsighted in 17 days, she said. No wonder the tortured artists seem a bit wet to her.

This hard-headed, business-driven approach must be rather alien to Arab novelists, for whom, thanks to copyright issues, rackety publishers and occasional political opposition, it has usually been difficult to make a living by the pen. A symposium on the effect of the internet on Arabic literature produced the startling statistic that 80 per cent of Arab authors pay to have their own work published. For those who persist, a rather old-punkish set of ideas about selling out seems to be the result. At a conference on the Arab novel, Ibrahim al Koni, Gamal al Ghitani and Fadhil al Azzawi were united in deploring the rise of the Arabic blockbuster on grounds of inauthenticity. Arab literature, said al Koni, was "a precious, spiritual product", rooted in a sense of nomadic freedom. To complete the romantic, jazzily counter-cultural atmosphere, two of the participants in the debate were wearing berets.

Still, the idea that literature should be a higher calling, set apart from the tawdry world of commerce, is far from an exclusively Arabic one. Margaret Atwood, appearing via video link from Toronto, mourned the incursion of marketing departments into the editorial process. "Oh dearie me," she said laconically. "Publishing is not really a business. It's an art and craft with a business component... Each book is a complete artefact. It's not like any other book. And you can't just mass-sell big chunks of book." She had, of course, just appeared in the widely trailed PEN censorship debate, her way of mending fences after her public withdrawal from the festival. Joining her on the panel had been the Ukrainian novelist Andrey Kurkov, a man who got a spontaneous round of applause during his own Q&A with Paul Blezard for a hair-raising anecdote about how he got published. He had to do it himself, purchasing six tonnes of paper on his own account. He had sent 10,000 copies to a company in Odessa on a sale or return basis and never got paid, so, naturally, he went to investigate. When he arrived, the warehouse manager told him he could have the books back if he could take them away himself. So he commandeered a hearse, bribing the driver to let him store his books in it overnight. It was then a race to clear them out before the driver's 11.00am funeral appointment. Far from being demoralised by the experience, such absurdities, Kurkov said, were what he liked about living in Ukraine. Life in Europe was just too boring.

The veteran science-fiction writer Brian Aldiss offered a likewise cheerful show of indifference to financial concerns. Aldiss, now deep into his eighties and still going strong, has three titles appearing this year alone. "I do think my prose is improving," he said, "because my sales are going down." He nodded across the room at Louis de Bernières. "This chap who wrote whatnot's mandolin," he said. "It's his eighth book [actually, his sixth], and this has brought him enormous, ah, shekels, shall we say? It does happen. It's happened to me once or twice. In fact one time, I had a book... and it rose to the top of the bestseller list. But then I saw there was another novel, with a very dull title. 'Why is everyone reading this?' I thought. 'The Godfather?'" He chuckled. I confessed that it hadn't struck me before what a bad title that was. "Not inspiring," he said, "but of course, once it's accepted..."

No small portion of the de Bernières fortune will have resulted from the inclusion of Captain Correlli's Mandolin on British school syllabuses. It's a distinction which has a downside, as the author explained: "You get these admiring letters from 15-year-olds saying: 'I loved your book, but could you explain your use of symbol and metaphor?' Come on, I'm not that stupid." He mused. "It's a bit like those emails you get from Nigeria, you know? 'I have an arms contract with the government but I need some money to get the deal finished. Please send me £13,000 and one day I'll send you four million...' I always reply to those."

If, as Mohammed Bennis said, the greatest prize is to be translated, it's fitting that the last of the festival's scheduled events should have been an English-language tribute to the great Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish, who died last year. Seven British-based poets, including Simon Armitage and Carol Ann Duffy, gathered to read some of Darwish's poems and some of their own. The Guyanan poet John Agard turned in a particularly fierce rendition of Darwish's hymn to Damascus, The Flute Cried, punctuated by wild lilting blasts on an ocarina. It was a suitably transporting moment, and a lovely one.

However, no book festival summing-up would be complete without a survey of its best lines. For some reason, on this occasion, they are all extremely grisly. The British adventurer Sir Ranulph Fiennes displayed an unexpected sense of comic timing during his packed interview with Aiden Hayes. Of Charles Burton, his companion during his record-breaking journey around the world's polar axis, Fiennes recalled: "Charlie... got fungus under his feet. And what happened was the skin fell off, so when he skied, he had no skin under one foot. So it was uncomfortable. He then got haemorrhoids. And then one day he fell over and cracked his head on a rock. His eyes filled up with blood," Fiennes frowned, "and he started to whinge." This got one of the biggest, not to say most nervous, laughs of the festival.

Meanwhile, Andrey Kurkov spoke about being quizzed by a pair of Ukrainian generals after a public figure was poisoned in circumstances reminiscent of one of his books. The anecdote ended on the reflection that: "People who poison other people professionally don't read novels. They read professional literature." And Paul Blezard, a man whose interview schedule over the past few days can scarcely have permitted him to breathe, much less sleep, improvised in conversation with Karin Slaughter this extraordinary pensée on the appeal of crime fiction: "It's where the envelope of niceness gets rough and crusty." Who could disagree? Still, at EAIFL, the envelope of niceness remained fresh and smooth throughout. That makes it a triumph in my book.