There are many images associated with the biblical Christmas and nativity: the holy family sheltering in a stable, the infant Jesus in a manger, hosts of angels, a gathering of shepherds and animals. However, it is the image of three "wise men" guided to Bethlehem by a star from the east that has captivated thinkers, writers and artists for more than two millennia.

Such is the appeal of the magi - the Greek word magoi means "wise man" and is derived from an older Persian word for priests - that even the phrase that describes their gifts, the very first Christmas presents, of "gold, frankincense, and myrrh" became inseparable.

In art, the adoration of the magi appeared earlier and more frequently than any other scene associated with Jesus's birth, and by the 6th century no nativity was complete without them. The list of artists drawn to them reads like a Who's Who of European art: Giotto, Botticelli, Bosch, Brueghel, Leonardo, Tintoretto, Titian, Rubens and Rembrandt.

The traditional image of the wise men is of three stargazing philosophers named Caspar, Balthazar and Melchior. Balthazar is often identified as African and Melchior as a youth, while Caspar is the aged man who kneels and kisses the infant Jesus in countless paintings. Not only do they represent wisdom and secular authority, their adoration recognises the infant Jesus's spiritual and temporal power in the Christian faith as both the son of God and as a king of his people.

Yet despite the detailed later narrative traditions surrounding the magi, there is scant information about them in the Gospel of Matthew, their biblical debut: " … wise men from the east came to Jerusalem … and lo, the star which they saw in the east, went before them, till it came and stood over where the young child was. And when they saw the star, they rejoiced with exceeding great joy. And they came into the house and saw the young child with Mary his mother … and opening their treasures they offered unto him gifts, gold and frankincense and myrrh." (Matthew 2:1, 9-11)

Remarkably, Matthew does not even give the wise men's names - these only emerged in the 9th century - or the state where they came from, or how old they were. Added to this, neither the Gospel of Luke nor the Quran, both of which contain detailed descriptions of the nativity, mention any wise men, magi or kings at all.

As Robin M. Jensen, author of Witnessing the Divine: the Magi in Art and Literature, stresses, the very idea that there were only three wise men was also a later construct as early depictions of the magi range from two to 12. "Their assumed number was undoubtedly derived from the three gifts presented to Jesus in Matthew."

If many of the details associated with the magi accrued over the centuries, Matthew and others established their association with the Orient at a very early stage. Some of the earliest depictions of the adoration of the magi appear on sarcophagi dating from the 4th century and on these the wise men are dressed in clothes that would have been unmistakably Persian or "eastern" to contemporaries and are accompanied by camels.

For Judith Weingarten, an archaeologist and member of the British School at Athens, there is little doubt that "the belief in the early church was that the magi were Persians. There is even an Apocryphal Arabic Gospel of the Infancy which appears to state that they were indeed Persian magi".

Even in the 10th century the Baghdadi historian and geographer al-Mas'udi, known as the Arab Herodotus, provides a version of the legend that confirms this link, while in the 1270s the Venetian traveller Marco Polo recounts tales and anecdotes that confirm the magi's Persian origins and final resting place. "In Persia is the city of Saba, from which the Three Magi set out and in this city they are buried, in three very large and beautiful monuments, side by side … The bodies are still entire, with hair and beard remaining."

Despite the early connections between the magi and Persia, ideas about their origins continued to evolve, particularly in medieval Europe. Weingarten again: "It was in Europe that the current image of three kings was created (one gift = one king). To further dramatise the coming of the Nations to Christ, one King was made into a black African, another an Oriental or an Arab, and the other a European."

By the 14th century not only had one of the magi become black, they had also become kings. One of the most important figures in the transformation of the magi was John of Hildesheim, a Carmelite monk whose Historia Trium Regium became one of the most popular accounts of the "three kings". In it, Hildesheim maintained that Balthazar was from "Saba" where "there groweth incense more than in all the other places of the world; it drippeth out of certain trees"; that Gaspar, who gave the infant Jesus myrrh, was an "Ethiope"; and that Melchior, who gave the gift of gold, came from Arabia.

"Now ye shall understand that there be three Indies of which these three lords were kings. In the first India was the land of Nubia and also the land of Arabia; and in those lands reigned Melchior at the time that Christ was born."

By the beginning of the 1st century, the supposed time of the biblical adoration, frankincense and myrrh were highly prized. Luxury commodities that had been traded throughout Arabia and the Middle and Far East for almost 3,000 years, frankincense, myrrh and spices were the oil of their day, making the peoples of Southern Arabia the envy of all antiquity and conferring a degree of wealth that became legendary.

The Romans, who used imported gum-resin as incense in temples, at cremations and as a cure-all for everything from haemorrhoids to leprosy, even described the region we now know as Yemen - the home of the trees that produced frankincense and myrrh - as Arabia Felix, or "blessed Arabia".

For members of the early Christian church and later medieval and Muslim commentators, however, the gifts presented at the nativity were charged with a symbolism that extended beyond their financial value. While the gifts of gold and frankincense recognised the infant Jesus's temporal power and divinity, myrrh, used as it was in the anointment of corpses, was seen as a precursor not only of his role as a healer, but also of his death.

In his Story of the Prophets, the prolific 7th century Yemeni narrator and Tabi'in, Wahb ibn Munabbih, quotes a conversation between King Herod and the magi regarding the meaning of their gifts, in which they explain: " … gold is the most noble of things to be possessed, and this prophet is the most noble of the people of his time. With myrrh, wounds and cuts are healed, and this prophet will be a physician … the frankincense because its smoke reaches the sky like … no other thing, and this prophet God will raise to the sky like no other in his time was raised."

Each generation and each faith has refashioned the image of the magi to their own ends and it is this flexibility that has allowed the story to endure. During the Renaissance, real European kings played magi in outdoor festivals, and during the 16th century the magi story even helped to inform a European imagination struggling to come to terms with the discovery of the New World, with the adoration used to illustrate to newly encountered indigenous peoples how they should worship the God of Christianity.

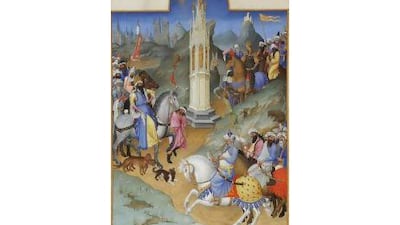

From wise men and magi to travellers and kings, it is through art that we come closest to understanding the magi and their journey from the sacred to the profane in all their cross-cultural complexity. They are a product of both East and West and for Caroline Stone, author of We Three Kings of Orient Were, nowhere can this be seen more clearly than in the depiction of the magi in the 15th century French illuminated manuscript the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry.

"The Three Kings appear on horseback with their retinues at the meeting of the three ways - always a place of mystery - outside Jerusalem. Their sumptuous clothes, flowing beards and glittering scimitars proclaim them kings from the Arab East, and the glowing colours lend the little painting something of the look of a Persian miniature. For a moment, the sober Christian story seems to shimmer and blend into the marvellous tales of The Thousand and One Nights."