The first Diriyah Contemporary Art Biennale opened this month just outside of Riyadh. A total of 63 artists are included in the inaugural exhibition Feeling the Stones, which considers how a country like Saudi Arabia, with its major societal changes, can chart its future.

Curated by Philip Tinari, director and chief executive of UCCA Centre for Contemporary Art in Beijing, the show includes old and never-before-seen works, with about half of the presentations commissioned for the biennale.

Here are a few of the standout works at the Diriyah Contemporary Art Biennale that visitors can see:

Andro Wekua, 'All is Fair in Dreams and War' (2018)

Equal parts captivating and memorable, Wekua’s melancholic, at times apocalyptic, video work oscillates between visions of dreams, nightmares and glimpses of a dystopian world.

Paired with a haunting track thundering and slicing metallic sounds, the five-minute film is at its most striking when it depicts a burning palm tree. As flames swallow up its fronds, the tree appears to be shrieking over a glistening piano tune.

While Wekua’s visuals may seem surreal at first, one begins to realise how much they mirror "real life" – particularly scenes from wild fires that have ravaged the US West Coast this year. The weeping palm, alight and helpless, symbolises the world as it is today.

Lei Lei and Chai Mi, '1993-1994' (2021)

In this moving two-channel installation, the artists are presenting footage shot in the UAE during the 1990s. Much of the material was recorded by Chai’s father, a Chinese worker who lived in the Middle East for seven years and recorded his experiences with a videocassette recorder.

We hear Chinese pop music, recitations of poetry and musings by the main subject, and, in one of the most human moments, a conversation between father and daughter about their time apart.

Several things unfold in this near-hour-long work, not in the least glimpses of a specific time in history when globalisation in the Far East and Middle East were merging, but perhaps what is most valuable is the perspective from which this history is told – a worker entering a new culture, brought to a distant land for the prospect of greater income. In the Gulf, it is a story that repeats itself time and again.

1993-1994 is one of the subtler works in the biennale, but nonetheless significant for its portrait of labour and sacrifice that exists in a truth outside of national myths.

William Kentridge, 'More Sweetly Play the Dance' (2015)

A danse macabre plays out on an expansive screen that goes from one corner of the room to another. A parade of characters emerge from left to right, taking turns to move to music by the African Immanuel Essemblies Band as it is played on four megaphones.

Kentridge is known for his hand-drawn charcoal animations that contemplate apartheid and injustice in South Africa. In this work, the artist uses Johannesburg as the setting for the procession, performed against a smudgy charcoal backdrop with grass and hints of industry littered around, but his ideas expand their geographical markers.

More Sweetly Play the Dance reflects on the passage of time, the frenzy and complexity of work and life, and mortality. Played in a loop, the characters on the screen could go on forever, marching along through life and death. There’s no stopping either.

We are all part of the dance – politicians gesticulating from podiums, office workers hunching over typewriters and desks, labourers and farmers carrying their crop, as well as a slew of newfangled hybrids of machine and man or machine creatures. Towards the end, a march of hospital patients wheeling around their IV drips brings the present into stark view. Though the work was created in 2015, in the midst of the Ebola outbreak in parts of Western Africa, it continues to resonate as issues of public health, mortality and safety plague us in different ways today.

Sarah Brahim, 'Soft Machines / Far Away Engines' (2021)

A highly poetic and thoughtful work, Brahim’s performance and video installation charts what she calls the “morphology of breath” and “how it changes, the different forms it could take, the breath around the body", she says.

At the biennale, the work excels not only in its concept and content, but its presentation. It stuns viewers then slows them down as Brahim’s subjects flit across the 10-channel installation – men and women relate to, gesture toward and sense each other through fluid and deliberate choreography.

While many of the other works in the exhibition looked at ecology and a post-pandemic future through nature, it is the artist’s focus on body and breath that makes it stand out. With the pandemic far from over and a new variant on the loose, the breath also carries with it fear and anxiety, but Brahim’s work reminds us that it is an integral, precious component of life.

“The breath is a tool to ground ourselves. It’s something we can push if we want to accomplish a certain energy. Our breath constantly carries us, it is an engine that our body never tires of,” the artist says.

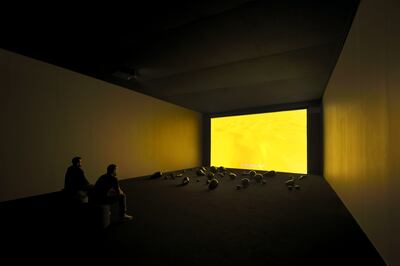

Monira Al Qadiri, 'Holy Quarter' (2020)

A series of glass sculptures are arranged on the floor. Shots of the Rub Al Khali or the Empty Quarter, sweep across a screen. Al Qadiri’s esoteric Holy Quarter draws from the story of British explorer Harry St John Philby, who ventured through the desert region to find the lost city of Ubar.

During his search, he came across a crater, which he mistook as the city and called it “Wabar”. The video’s narrators are the tiny black stones left behind by the meteoric impacts that created the crater, and they are also represented by the blown-glass sculptures.

Al Qadiri’s work not only looks back at Philby’s journey, but also tries to break free of a human-centred understanding of ecology. By giving narration away to the “extraterrestrial”, the artist asks us to imagine a future determined not only by man, but also by cosmic forces outside of our realm of control.

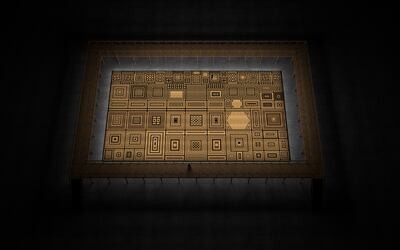

Dana Awartani, 'Standing by the Ruins of Aleppo' (2021)

In the weeks leading up to the biennale, Awartani had been laying out adobe bricks to dry in the sun before arranging them to create her installation Standing by the Ruins of Aleppo.

The mosaic work is an artistic recreation of the courtyard of the Grand Mosque of Aleppo, damaged during the Syrian Civil War.

In her work, the artist explores the destruction of cultural heritage, whether through war or neglect. Standing by the Ruins of Aleppo is also a nod to her mixed background of Saudi, Jordanian, Palestinian and Syrian heritage, and a reminder of the irrevocable loss of culture in the Arab world.

Deliberating using clay to mimic the surrounding traditional architecture in Diriyah, the artist says that growing up she also saw how the Middle East had a “self-colonial perspective” when it comes to its heritage.

“The way we build our architecture in Saudi does not speak of the local architecture, the way we decorate our homes is very modern European … So my work fights against that,” she says.

Running until March, the Diriyah Biennale Foundation, the organisation behind the event, will host a public programme in the coming months at Jax District for visitors. These include panel discussions with artists and experts, as well as educational activities for children. More information is available at biennale.org.sa