For many expatriates, growing up in the Gulf is linked to an unshakeable feeling that you'll never truly belong.

Inevitably, the longer one lives apart from the homeland listed on their passport, the more issues emerge. Ambitions are laid out in the precarious shadow of residency visas and sponsorships. Sometimes, the best laid plans for a lifetime spent in the region are cut short by an unexpected blow, forcing families to uproot themselves, either heading back to their native countries or trying their luck elsewhere.

For many that have been in that position, it can be hard to wrap their minds around its ramifications.

A new exhibition at the Project Space, NYUAD Art Gallery's auxiliary venue, underscores these tensions and concerns, from a specifically Egyptian point of view. But as is the case with much art, specificity of experience can easily be transposed to other cultural perspectives.

Being Borrowed: On Egyptian Migration to the Gulf opened earlier this month and will be running at Project Space until February 7. The exhibition presents works by 21 Egyptian artists across a range of media, from photographs and video works to installations and textiles.

Curated by Farida Youssef, alongside Farah Hallaba and Ali Zaaray, Being Borrowed comes as a sequel to an exhibition presented in Cairo in 2022.

However, the show in Project Space is distinct in the way it addresses the metaphysical consequences of migration to and from the Gulf that separates it from the show in Egypt, which was more concerned with the concrete experiences of living in the region and did not delve into notions of belonging as much.

The first exhibition came as a result of an artistic workshop at Cairo’s Contemporary Image Collective that was organised by Anthropology Bel 'Arabi, an initiative that founder Hallaba says, “aims to create a collaborative engagement with anthropological questions or themes.”

“One of them was my own personal experience of living in the Gulf,” she says. “We did a workshop, where all of these artists were participants.”

Most of those presenting their creations were completely new to art before enrolling in the workshop, and had signed up for the programme as a way of sifting through their own experiences of growing up in the Gulf before returning to Egypt.

“At some point, we felt like we were getting out the things that we really want to share with a wider audience,” she says. “Because it's a very normalised experience, despite how common the experience of migrating to the Gulf is in Egypt. No one asks the question of how the experience is shaped and the baggage we carry [as a result].”

Hallaba says her experience of growing up in Riyadh was an impetus for the workshop, as well as the fact that her father is still in the Saudi capital, “living there temporarily for 30 years”.

“The framework of temporality was how we understood all the questions we were trying to ask,” she says. “It's a very understudied topic. What we would do [in the workshop] is mainly engage with pop culture, because there is very little literature on this experience, especially the middle class experience. We would gather, we would ask the question, and we would then realise patterns.”

As a whole, Being Borrowed can be seen as a coherent experience of an Egyptian spending their childhood and formative years in the Gulf, before leaving to pursue higher education.

This timeline, curator Youssef says, was a common one for most of the participants of the workshop.

“I wanted to bring forward the experience as clearly as possible,” she says. “The common pattern in the experience was that people come to the Gulf as children, and then they leave the Gulf when they're about to enter university. In between, we get to unpack that experience.”

Being Borrowed opens with Nourhan Abdel-Salam’s Place of Birth: Oman. The work features a pair of childhood photographs of the artist and her friend, alluding to the friendships formed at an early age and which persist despite the growing distance. The two friends are still in touch, even after Abdel-Salam left Oman and has since been unable to return. A letter appears alongside the images that shows their correspondence with hopes that they’ll be united again.

Aya Bendary’s A Carrier, on the other hand, literally begins unpacking the experience of a temporary existence in the Gulf. The installation focuses on a suitcase as the centrifugal symbol of migration. It is left open and bursting with printed fabrics, some of which reach the ceiling. Words are printed on the textile scraps, touching upon Bendary’s experience in the Gulf, including ghurba (the feeling of alienation), kaaba, Umrah and travelling.

“Some moments in the exhibition are very literal,” Youssef says. “It's not just focusing on the problem itself. But it's also focusing on what I would term as a catharsis. The exhibition is migrating back to the Gulf. In a sense, it's reliving the experience of migration in the hope of healing.”

Hossam Gad’s (A)Normal, meanwhile, encapsulates the life of a man named Mohamed Hashem who spent years in Saudi Arabia, with passports and letters that symbolise his transformation as a person while living abroad. The installation goes against the grain of stereotypes that those who live in Saudi Arabia develop heightened religious sentiments, instead showing Hashem’s transformation from a bearded man in a galabeya to a moustached man in a suit.

“Gad talks about a family member’s experience of travelling to the Gulf as a Salafi and then coming back as a businessman, which is contrary to the stereotype that we have about Arabs migrating to the Gulf.”

Not Denying Melancholy by Farida Serageldine Kamel is an homage to the abaya the artist grew accustomed to wearing while living in the Gulf. A translucent fabric on a mannequin, the work shows that expats pick up customs from their time in the Gulf, which they grow to miss when they return home.

“With these works, the identity is foreshadowed as a question of presence and absence and not really something static,” Youssef says.

The exhibition then moves on to a stack of boxes and an upholstered chair, an installation by Lina El-Shamy called Deferred Homes and Boxed Objects that show the melancholic preparations of moving.

Photographs that accompany the work touch upon the differences between furniture that decorates an apartment in the Gulf compared to a family home in Egypt, with the former being lighter and symbolising their temporary status, while the latter is usually made from wood, ornamented and harder to move.

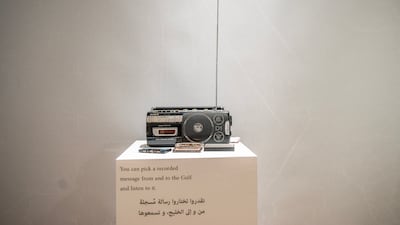

As the exhibition gracefully manoeuvres through more archival materials and family photographs, it strikes the senses as a time capsule, touching upon music, magazine headlines and other pop culture elements that were rampant in the Gulf in the past.

The exhibition then concludes, in metaphoric precision, with Omar Mansour’s Working Title. The installation features a study desk, decked with psychiatry books that allude to the mental health of young adults who return to Egypt after spending years in the Gulf.

“There’s almost a psychoanalytic perspective to the exhibition,” Youssef says. “I tried to twist it in that sense for this edition. It’s really about what happens to belonging, what it means to belong, and memory, homes and identity get affected by the notion of belonging.”

Being Borrowed: On Egyptian Migration to the Gulf will be running at Project Space until February 7