The future of Northern Ireland will be built on quicksand unless politicians are willing to compromise to end the deadlock over the Protocol, the former Irish leader Bertie Ahern has said.

Speaking ahead of the 25th anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement, the former Taoiseach (Irish prime minister) and Fianna Fail leader suggested political parties in Northern Ireland should look to history for inspiration for solutions.

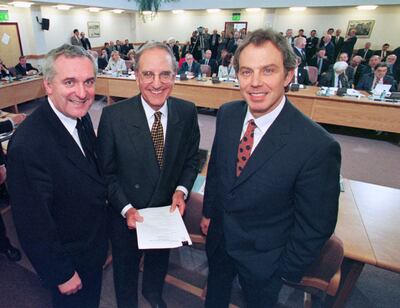

Along with Tony Blair, Mr Ahern co-signed the landmark peace accord on April 10, 1998, bringing an end to decades of violence in Northern Ireland known as The Troubles.

Giving evidence to members of the Northern Ireland Affairs Committee in the UK Parliament on Monday, Mr Ahern recalled that at the time of the deal, both nationalist and unionist politicians were “prepared to work incredibly hard to try and see if we could get compromise”.

He suggested that a similar dose of pragmatism is needed by political parties in Northern Ireland to solve the crisis.

The Democratic Unionist Party is blocking the functioning of power-sharing at Stormont and has made clear it will not allow devolution to return unless major changes to the protocol are delivered.

The Protocol is a key part of the Brexit withdrawal agreement struck by the UK and the EU in 2019. Designed as a means to keep the Irish land border free-flowing, it moved regulatory and customs checks on goods to the Irish Sea, creating economic barriers on trade between Britain and Northern Ireland.

Many unionists in Northern Ireland are staunchly opposed to arrangements they argue have undermined the region’s place in the UK.

During the session, Mr Ahern was questioned by DUP MP Jim Shannon who warned about the “fires of anger” among unionist communities in Northern Ireland, as they feel they are not being listened to.

Asked by The National if he was worried about a potential return to sectarian violence if the political crisis drags on, Mr Ahern said he was not.

“I don’t think that’s on the agenda,” he said. “I am hopeful we can find a compromise.”

Mr Ahern told the committee it would be “stupid” to ignore unionists’ concerns, but their demands “can’t be fully adhered to” in any agreement that will resolve the stalemate.

He said without compromise among Northern Irish politicians, “we’ll run into a position where for where for the longer term … we haven’t got a solution and we don’t have institutions [in Northern Ireland].

“There lies the problem.

“So, in the absence of compromise we’re building a future that will be on quicksand and that’s my concern.

“I am 100 per cent for compromise, 100 per cent for trying to accommodate the concerns of people, but I do not think that we can long-finger this — and I’m not talking about April, that’s not the issue — into the distant future.

“That would be a grave mistake.”

Mr Ahern said if Brussels and London grasp that “there is as a UK internal market that must live beside a single market and that there’s unique differences,” then a solution would be possible.

“I do not believe that’s impossible but it does require some compromise.”

While Mr Ahern said he was not interested in giving a commentary on “the rights and wrongs of Brexit” he stressed that politicians in Northern Ireland had found themselves caught between two narratives they have no control over — one from London and the other from Brussels.

He said the consequences of the UK’s decision to leave the EU had created “a huge problem for six solid years” and had been “very testing” for political parties in Northern Ireland.

“The difficulty for the parties in Northern Ireland today is they don’t control that position. They don’t control the British government policy on it and they don’t control the European Union policy on it. And that makes life difficult. Of course, they all have views on it but ultimately they can’t settle that issue.”

He hailed the late Lord Trimble, former first minister of Northern Ireland, who was a crucial unionist architect of the Good Friday Agreement, for making “incredibly brave decisions”.

“If you ask me today, I think the same political leaders of a new generation are around but what has created so much [of a] problem for them are things outside of their own control,” he said.