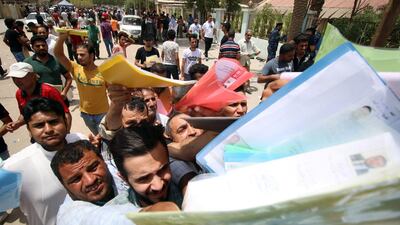

After using tear gas and water cannons to disperse some 250 protests outside the southern Iraqi Zubair oilfield near Basra, police moved in with batons.

In the 11 days of continuous protests at a lack of government services, long power cuts and water shortages through the blisteringly hot summer months in towns and cities across south and central Iraq, some eight people have been killed and 60 injured.

But the irony of the location of the protests hasn’t been lost on Iraqis. The country’s southern oil and gas terminals currently account for 100 per cent of the central government’s crude exports. In May, the sales yielded $7.55 billion in revenues, nearly $250 million a day – yet basic services are inadequate, jobs are scarce and disillusion is high.

Stagnant water with sewage has caused health problems and tap water is sometimes contaminated with mud and dust. Electricity is cut off for seven hours a day.

Iraq’s southern Shiite heartland has long been neglected, despite its oil wealth. First by deposed dictator Saddam Hussein and then by the Shiite-led government that followed him. Including, say many, Prime Minister Haider Al Abadi – towards whom much of the recent anger has been directed.

__________

Read more:

Iraqis protest at entrance to Zubair oilfield

Iraq protests spread, fuelled by anger and hopelessness

Two killed in southern Iraq as protests spread

Basra protests gather momentum and enter fourth day

__________

"Investment projects in Basra were intended to raise the province's own [electricity] production capacity. However, due to familiar problems of corruption and inefficiency, the hoped-for targets have not been met," Benedict Robin-D'Cruz, an Iraq researcher who has been mapping the protests, told The National.

Most Iraqis believe their leaders are monopolising the country’s oil wealth.

The hostility is largely directed towards a political elite deemed corrupt at a time when the feeling that politicians are unreliable is at an all-time high. Over the past week, protesters have attacked government buildings and branches of political powerful Shiite militias.

Undeterred by the scorching summer heat, demonstrations spread from Basra to Samawa, Amara, Nassiriya, Najaf, Karbala and Hilla. Minor demonstrations also broke out in Baghdad. On Wednesday, small protests broke out in Abu Al Khasib, south east of Basra city.

To most, however, these protests don’t come as a surprise. Each summer, when temperatures hit 50 degrees Celsius and basic services break down, disgruntled Basrawis take to the streets.

But behind the chaos of burning tyres and tear gas, the absence of an overarching leadership underscores the severity of their grievances and something of a change in a country where politicians regularly whip up their supporters to score political points against rivals.

This time, Iraqis are not being rallied by political parties in hope of compensation. Instead, they are spontaneously spilling onto the streets to demand basic rights.

“I live in a place which is rich with oil that brings billions of dollars while I work in collecting garbage to desperately feed my two kids,” one 22-year-old protester told Reuters. “I want a simple job, that’s my only demand.”

These protests, says Mr Robin-D’Cruz, lack coherent political organisation or a clear political agenda.

Populist Moqtada Al Sadr, whose coalition won the highest number of seats in May’s elections, is likely to attempt to politicise the plight of the people. However, says Mr Robin D’Cruz “he will also be wary of unleashing forces he cannot control.”

In the past, Mr Al Sadr has been accused of rallying protests against the government. While there is no evidence at this stage that Sadrists have orchestrated the latest demonstrations, “their suspected involvement will be used by other factions to delegitimise the protests and potentially set the stage for a crackdown,” he said.

One Basra resident, who asked not to use his name, told The National that police had been arresting people and had beaten protesters. On social media, images were shared of wounded men who had allegedly beaten by the police.

At the gate of Zubair field on Tuesday, witnesses said that police beat protesters' backs and legs with batons and rubber hoses. On Saturday Mr Al Abadi deployed six Emergency Response Division and three Counter-Terrorism battalions to the south.

Iraq’s battle hardened Counter-Terrorism officers were last deployed in the liberation of Mosul from ISIS. Fighting alongside the Counter-Terrorism forces were hundreds of Shiite militiamen from the Popular Mobilisation Units, most of whom hailed from Iraq’s southern provinces.

“This is an unprecedented response by the government,” said Dr Renad Mansour, a research fellow for the Middle East and North Africa at Chatham House. Baghdad, says Dr Mansour, is worried because it is in the midst of a government formation and therefore more vulnerable.

These leaderless protests have underscored the widening schism that exists between Iraq’s political elite and their people.

“There’s a huge divide between that small minority and Iraqis. It frustrates them. There’s disillusionment and hopelessness,” said Dr Mansour. “These protests are against the political elite.”

The wider the gap between the demonstrators and the central government, the more Baghdad is likely to crack down on its restless people.

As well as the eight people who have been killed so far, authorities claim that over 260 security personnel have been wounded.

“There is an emerging rhetoric coming from supporters of the embattled establishment and even Abadi to some extent, reminiscent of the rhetoric surrounding [former prime minister Nouri al-] Maliki’s violent crackdown on protests in 2011”, explained Mr Robin-D’Cruz. “[They are] talking of ‘infiltrators’ and ‘Baathists’ amongst the rank of the demonstrators.”

So far there has been no evidence of political ‘infiltrators’. Instead, Iraq’s protests are the organic outcome of unanswered grievances, most of which were momentarily suppressed during the fight against ISIS.

A temporary end to demonstrations, says Mr Robin-D’Cruz, could see the government reapply the tried and tested formula - “deploying resources to buy off opposition at key local sites.”

“They will hope that such measures, combined with overt, but targeted, repression, can buy them breathing space.”