TRIPOLI, LEBANON //It is almost eleven o'clock and people in the audience have long since broken their fasts, some have performed their evening prayers and are now sitting back to enjoy the night's entertainment.

But the crowd are not gathered around a television set in a living room or coffee shop to catch the latest instalment of a Ramadan series.

Instead, about 150 people at a cultural centre await the arrival of musicians, dancers and a hakawati, or traditional storyteller.

Once a staple of Ramadan nights in Lebanon and elsewhere in the Arab world, the art of storytelling art has all but died. People would once gather at the local ahweh, or coffee shop, to listen to performers retell fables and discuss life and politics but now they prefer to meet friends and family or converge to watch popular television dramas.

But there are still a small group of hakawatis in Lebanon keeping the tradition alive.

On a recent evening, in a courtyard at Tripoli's Beit Al Fann, or House of Art, a musical troupe from the besieged Syrian city of Aleppo played for guests, while a whirling dervish performed his dizzying dance in front of the stage.

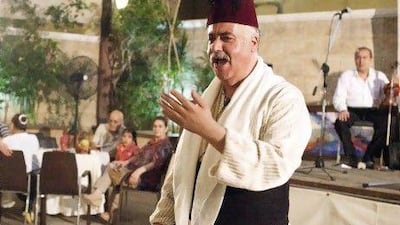

A portly man in a red fez, flowing cream robes, a wide, black belt, and carrying a walking stick, then wove through the audience before taking to the stage.

Nazih Kamareddine, a 52-year-old actor who believes he is one of only a few "real" hakawatis still performing in the Arab world, started acting at school.

Since then, he has not stopped performing. It was in 1989 that he first performed as a hakawati, when a theatre group needed someone to step into the role.

"It was beautiful," Mr Kamareddine said slowly, with a wide smile. "It is a very rare thing to be and to help preserve our culture and folklore. Hakawatis had a big role in society and would talk about everything."

On this occasion, he performs a short rendition of part of his favourite tale - Antara and Abla, an epic love story that can take 30 nights to recite in its entirety. He inserts contemporary references into his performance, speaking of how the main characters would contact each other by messaging on their mobile phones, bringing levity to the ancient tale.

Mr Kamareddine delights in regaling his audience with stories and parables interspersed with song and verse, something that Arab storytellers have been doing for hundreds of years.

Unlike the Levantine hakawatis of past decades, he does not perform every night to packed local coffee houses.

While the tradition has largely disappeared from daily life, it is revived in parts of Lebanon, particularly during Ramadan, when Mr Kamareddine and other hakawatis are commissioned for special performances.

Sara Kassir, a 28-year-old from Beirut, is one of the few female storytellers. She is involved in efforts to revive the tradition in Lebanon, which she said has helped to introduce hakawatis to a new generation.

"But many people still have no idea what it is all about, especially as I am a female performer," she said. "But it is about serving our oral culture, which could die out."

Abdul Nasser Yassin, who runs Beit Al Fann in Tripoli's Al Mina area where Mr Kamareddine's performance was held, believes the last genuine hakawati performed in the city in the 1950s.

"Now the memory is being recreated," he said.

This being Lebanon, Mr Kamareddine's performances and conversations never veer far from politics. One of the stories he incorporates is that of Rafiq Hariri, the late Lebanese prime minister who was assassinated in 2005.

"It is a story about his life, but also his death. About one man and four million Lebanese people - the story of a country. Every new political event, I weave into my performances," he said before breaking into verse, singing about how Lebanon bleeds because it is divided by groups whose loyalties lie with foreign powers.

Among his favourite topics is the wave of Arab uprisings and the war in Syria, the border of which is just 35 kilometres away from this north Lebanon city.

"For the last 12 years I have told people to start a revolution," he said. "They were sleeping for way too long. Now they have woken up."

Driving late at night through the streets of Tripoli to the neighbourhood of Abu Samra - where Mr Kamareddine lives and runs a small cafe and electrical repair shop - the city is bustling with people, some seated around television sets at outdoor restaurants smoking shisha pipes.

Mr Kamareddine laments the faded role of the hakawati, but believes the old tales still resonate today.

"Hakawatis give people help and positive messages that go on forever," he said later, seated on a plastic chair under bright fluorescent lights outside Cafe Kamareddine. "Hakawatis will never die out, but it depends on who can continue the tradition."

zconstantine@thenational.ae