Syrian refugees and exiles are divided over whether members of the security forces who defected from the government should be prosecuted for war crimes, or serve as key witnesses to bring senior officials to justice.

Hundreds of thousands of people have been killed in the civil war that has been marked by atrocities since it broke out in 2011.

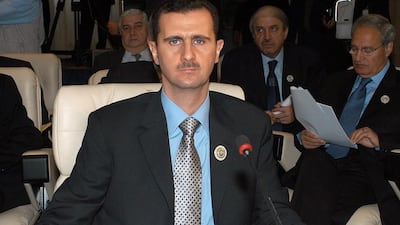

In Germany, home to 600,000 Syrian refugees, authorities have used universal jurisdiction laws to prosecute crimes against humanity and seek justice for victims of torture and extrajudicial killings by President Bashar Al Assad's forces.

In the first case to be brought to a German court, the trial opened in April of two former Syrian intelligence officers on charges of torture and sexual assault.

The suspects had defected in 2012 and were granted asylum in Germany.

Many of the Syrians now in that country are asking if the defectors are friends or foes.

"The trial in Germany is wrong, strategically and morally," said Fawaz Tello, a veteran Syrian dissident.

"Defectors risked their lives to join the opposition and discredit the regime.

"Who in their right mind is going to defect now when they see that people who defected in the first months of the revolution are being put on trial?"

The Syrian government has regularly rejected reports of torture and extrajudicial killings documented by international human rights groups.

Justice for victims

Mahmoud Alabdulah, a former colonel in the Syrian army's elite 4th Division, is one of hundreds of defectors who have given testimonies to German and French judicial officials collecting evidence of war crimes by the government.

Mr Alabdulah says a military card identifying his rank is the most valuable item of the few belongings he carried when he left Syria six years ago.

The pink, plastic-covered piece of paper has given more credence to testimonies he delivered in France and Germany against the Syrian government, he says.

"I saw soldiers being executed for refusing to open fire on protesters and heavy artillery fired towards civilian areas," said Mr Alabdulah, 56, a father of five, rolling a cigarette in a modest flat in the eastern German city of Gera where he lives with his wife.

"I remember the night I decided to defect: February 13, 2012.

"I was praying in my room, lights off, at the Saboura military base [west of Damascus] and I said, 'God, I don't want to take part in such crimes, please help me get out of here'."

Campaigners have hailed the process in Germany as a first step towards justice for thousands of Syrians who say they were tortured in government centres.

Attempts to establish an international tribunal for the war had failed.

"No one has the right to tell victims they should not seek justice," said Anwar Al Bunni, of the European Centre for Constitutional and Human Rights, which is representing victims in the torture trial.

"Ignoring suspected war criminals is equivalent to white-washing the Assad regime."

The main defendant in the trial, Anwar R, is charged with 58 murders in a Damascus prison where prosecutors say at least 4,000 opposition activists were tortured in 2011 and 2012.

He has denied all the charges.

Anwar R was an intelligence colonel in Mr Al Assad's security system but defected in 2012 to Turkey, where he became active in the opposition Free Syrian Army.

He went to Germany in 2014 and was granted asylum.

Mr Tello said Anwar R was a member of an opposition delegation at UN-sponsored talks in Geneva six years ago, which were aimed at ending the conflict, making his trial a "humiliation" for opposition groups marred by infighting.

Mr Alabdulah questioned whether it was realistic for everyone who committed a crime to face justice.

As to whether he feared charges would be laid against him, he said his conscience was clear because he fought against Mr Al Assad's forces and ISIS militants before he fled to Turkey.

"We are not even close to winning the war," Mr Alabdulah said. "Even if we did, there should be some kind of a general amnesty.

"The Assad family and its most loyal lieutenants should be tried."