As he hops into a treatment room, the denim below Seif Salman’s right knee flaps where his leg used to be.

He is just one of the thousands of young Iraqis who took to the streets late last year, to the front lines in the country’s popular protest movement against what has become a crooked political system.

"I didn't see the shot, but I heard it," he tells The National. "I hit the ground before I saw what had happened to my leg."

He unflinchingly relives the moment through a grainy video on his phone. A tear gas canister continues to pump out plumes of smoke, though it is lodged below his knee. Another protester wraps a flag around the wound, a feeble attempt at a tourniquet. Without emotion, he watches himself writhe in pain.

Unshaven and stocky, Mr Salman is now receiving treatment the Baghdad Medical Rehabilitation Centre, a clinic run by Medecins Sans Frontiers. His leg was amputated, though he insists his wound has done nothing to dampen his spirit.

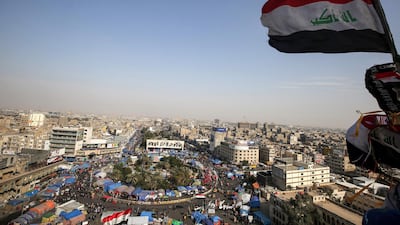

Soon he will be fitted with a prosthetic limb, and after that, he says he has no doubt he will return to Tahrir Square, the epicentre of nearly four months of protests in Baghdad.

Activists say that security forces have been intentional firing tear gas canisters at protesters’ bodies, and a slew of pictures on social media and WhatsApp groups show canisters embedded in the various limbs of maimed protesters.

Others hit in the face or head have not been as lucky as Mr Salman, with reports that dozens have been killed by the ubiquitous canisters.

Yet the zeal for change of the thousands who took to protest was met with brute force, the Iraqi War Crimes Documentation Centre has recorded 669 protesters killed in the final three months of 2019. Another nearly 24,000 were injured.

Literally thousands of young Iraqis are now living with similar life-changing injuries to Mr Salman.

Yet while the deaths of activists and protesters grab headlines and social media outrage – those who have had their lives altered dramatically are left to fend for themselves. But some are returning to the squares of the cities, picking up their protest once more, as though nothing has ever happened.

It is more than two months since Mr Salman travelled to Baghdad to join the protests that day from his home in Hillah on a branch of the Euphrates, about 120 kilometres south of the capital. He turned off his phone and told his family was visiting a friend.

He describes the euphoria of first walking into Baghdad’s Tahrir Square, where thousands of protesters are still camped out. “The square was everything Iraq could be,” he says.

He was part of a small group on the front lines, tasked with dealing with tear gas. They run towards the gas canisters, smothering them in blankets, or tossing them away.

It is dangerous, often taking them into the crosshairs of security forces.

Dr Saad Seleiman, 29, is one of the clinic’s doctors. As the violence peaked in October, he was part of a team running a clinic close to the action.

“It was a gush of patients coming at once, many injured patients, multiple areas... I was even choking from the smoke,” he recalls.

“Patients were afraid to be admitted to public hospitals, they feared being arrested."

Over the past few months, he says he has seen everything from gunshots wounds to amputations like Mr Salman's being carried out.

“I saw patients with live bullets, some of them had brain injuries, they had gunshots in their head, and in the abdomen, of course,” he recalls.

Outside, Seif teases another patient – Ali Salem Jassem, 21, a tuk-tuk driver from Sadr City.

His simple life ferrying shoppers around was upturned when protests broke out.

Tuk-tuk’s have become the ambulances of the front lines and a symbol of the revolution more widely.

Ali Salem remembers the night of November 7 well. As he sped towards the clashes, searching for those in need of help, he leapt from his Tuk-tuk to help a man and heard a bang.

“My leg went all the way back,” he says, tracing a scar with hand holding a cigarette. “It was like a feather, it was just dangling”.

His thigh is marked, front and back, the entry and exit wounds. Were it not for the treatment received at the field hospitals, he too might have lost a leg. But he shrugs it off. Just two days after being discharged, he hobbled back to Tahrir on crutches.

Looking at the scars on his thigh, Ali Salem could be forgiven for a harbouring hatred toward those who shot at him. But his anger, he insists, is at Iraq’s failing institutions, and those who lead them, not the government’s foot soldiers.

“The person holding a gun doesn’t know my intention,” he says.

“Maybe the guy who shot me was afraid."