Hundreds of thousands of Lebanese people from all backgrounds have been on the streets for a week, demonstrating against a political class they hold responsible for decades of wrongs and corruption.

Sectarian rivalries that politicians claim kept the country divided for half a century have fallen away.

The protests erupted close to the 30th anniversary of the signing of a document that shaped post-civil war Lebanon.

The Taif Accord was signed on October 22, 1989. It was praised as a gold-standard example of diplomacy when Lebanon’s 15-year civil conflict ended the following year.

Under pressure from external sponsors, warlords agreed on a new division of power, rebalancing of sectarian representation and move from physical to political battles.

Taif set the goal of moving away from sectarian representation. The accord tinkered with a system that favoured Lebanon’s Christian parties, giving the Sunni prime minister more executive power, partly at the expense of the president, and juggled other responsibilities.

Three decades later, street demonstrators in Beirut are demanding the end of sectarianism.

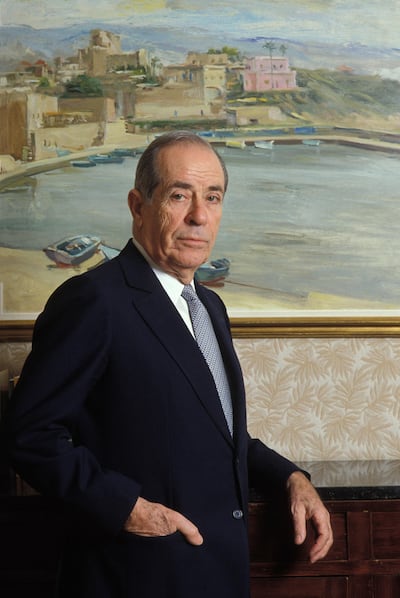

The accord made an international diplomatic star of its architect, Algerian envoy Lakhdar Brahimi, who ignored warnings by Lebanon’s elder statesman, Raymond Edde, that Taif was fatally flawed.

Edde, a major figure behind Lebanese prosperity before the war, viewed Taif as doing nothing to reform the political system. The accord gave a free hand, he said, to what he regarded as the ruinous Syrian Assad family’s influence over Lebanon.

Syrian dictator Hafez Al Assad invaded Lebanon in 1976, saying that he wanted to end the country’s civil war.

His son, Bashar Al Assad, did not leave until 2005, amid international pressure and mass rallies after the assassination of Lebanese prime minister Rafic Hariri, the driving force behind the country's postwar reconstruction.

A continuing UN trial in The Hague indicted four Hezbollah operatives for the killing.

The Taif deal eased the way for Hafez Al Assad to treat Lebanon as a vassal state, by not demanding the withdrawal of Syrian troops.

At the same time, the US gave a tacit go-ahead for the late Syrian dictator to implement Taif by force, crushing opponents of the accord in Lebanon.

Al Assad promoted former warlords from across the sectarian spectrum but he needed Hariri.

The late tycoon had excellent connections in the Arabian Gulf where he had extensive businesses and the base to help revive the postwar Lebanese economy, a major source of income for the Syrian regime.

Hariri and top businessmen linked to him distributed shares in various Lebanese assets they owned to Syrian regime officials in return for not sabotaging the country’s overall economy, which had prided itself on a tradition of laissez-faire.

Although Hariri’s murder led to the departure of the Syrian regime from Lebanon and a weakening of its control, it allowed local politicians to inherit a system of expropriation and many are still running the country today.

Imad Salamey, associate professor at the Lebanese American University in Beirut, said that Lebanese governments after 1990 should have acted on clauses in the Taif Accord that called for doing away with political sectarianism.

Mr Salamey told The National that the cross confessional nature of today’s protest movement and the focus on repairing governance offer the first tangible hope that Lebanon could get rid of the most damaging aspects its sectarian legacy, and possibly do away with political sectarianism in the longer term.

The Taif accord “reaffirmed and even consolidated” the sharing of spoils, Lebanese political researcher Joseph Bahout said.

“In that regard, Lebanon has the illustrious privilege of having been a pioneer in the creation of a system based on sectarianism and also a laboratory highlighting its dysfunctions and limitations,” Mr Bahout wrote in 2016.

The system was envisaged initially by the leaders of Lebanese independence as a way to bridge fissures between Muslims and Christians, and the country’s Arab and western cultural divide.

They wanted to avoid the spectre of a civil war, which occurred under the next generation of confessional leaders.

By the time the brutal 1975 to 1990 conflict ended almost everyone had fought everyone else at some point, shattering the country.

Mr Bahout said that by 1989, “after multiple rounds of fighting, more than 100,000 deaths and immeasurable destruction, all that the Taif Agreement did about sectarianism was readjust the old system”.

Under the Taif-based system, corruption became “an accepted form of political behaviour relatively quickly”.

“Over time, it translated into state inefficiency and the paralysis of decision making,” he said.

Poor governance steadily took a fiscal and economic toll. Public debt, at 150 per cent of GDP, is partly due to unaccounted spending by state organisations. The country today is in its worst economic crisis since 1990.

In the 1950s Edde wrote legislation that fortified property rights and introduced strict banking secrecy. The measures drew huge deposits from across the Middle East and beyond, especially among the Lebanese and Syrian diaspora in Africa and Latin America. For decades, Lebanon was the financial centre for the region.

The late Palestinian-Lebanese banker Youssef Baidas said the country attracted money “like the Suez Canal processed ships”.

Edde detested that Taif became Lebanon’s de facto constitution. He died in France in 2000, refusing to return to his homeland while Syrian troops remained.

A proponent of non-violence, Edde refused demands from his supporters for help to gather arms, in contrast to another Christian opponent of the accord – General Michel Aoun.

In 1988, then army head Mr Aoun attempted to become the leader of Lebanon when the outgoing president Amine Gemayel dismissed the civil administration and appointed a junta. Mr Aoun’s administration was formed on shaky constitutional grounds and was never widely recognised.

It ended when Syrian regime troops overran Mr Aoun’s men held up at the presidential palace. He fled to France in the middle of the night where he stayed in exile for 15 years.

Now 82, Mr Aoun has realised his 40-year ambition and is now the sitting president of Lebanon.

During the war, he was a fierce critic of the Syrian regime and its allies, but after his return to Lebanon, he signed an alliance with Hezbollah in 2006 and became a strong member of the pro-Assad March 8 Alliance.

To Hezbollah, he offered a sectarian shield to its militia – the only armed group allowed to retain arms after 1990 – under the auspices that they were just to drive out the Israeli occupation of the south. No longer did Hezbollah and its Amal ally just represent Shiites – with Mr Aoun they had sizeable Christian support.

The agreement was another step towards the presidential palace for Mr Aoun.

Today, Mr Aoun is again under siege, but from protesters demanding the government and the entire political class leave. In the first six days of the movement, the president did not utter a word about the protests other than opening remarks to ministers in Monday’s Cabinet session.

On Tuesday, the palace issued a statement saying rumours of Mr Aoun’s ill health or even death were exaggerated.

The protests have been leaderless and spontaneous. While this has brought mass appeal, it means there is no clear set of demands. While some things seem ubiquitous – such as an end to corruption, cronyism and incompetent governance – others are not.

Some want independent figures to lead, others want reforms and a Cabinet reshuffle. Some are calling for a new, non-sectarian electoral law – a perennial and thorny issue in itself. Also on the shopping list are early elections to end the control of the current parties in government.

Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah warned protesters on Saturday that they will not succeed in toppling the government and dismissed the movement as lacking longevity.

Nabih Berri, the former Shiite Amal militia commander and the current speaker of parliament who was installed in his position by Hafez Al Assad in 1992, shows no signs of wanting to leave.

On Tuesday, Druze leader Walid Jumblatt said the government should stay on. He was, in effect, throwing his hat in with Mr Aoun’s son-in-law, Foreign Minister Gebran Bassil, and Hezbollah.

This is despite Mr Jumblatt having been an outspoken Hezbollah critic for decades. He supported the Syrian uprising against Assad family rule, and his father, Kamal Jumblatt was killed by Syrian operatives in 1977. But Mr Jumblatt is also known as the cat of Lebanese politics, as well as its bellwether, which has helped his small Druze community achieve political importance.

A rare exception has been Samir Geagea, head of the Lebanese Forces militia-turned-political party. He announced the resignation of his cabinet ministers in response to the outbreak of the street demonstrations.

Mr Geagea famously paid for opposing Taif by becoming the only warlord to be tried and jailed for crimes during the conflict, upon the wishes of the Syrian regime. He was released in 2005, after 11 years in solitary confinement.

The now 85 year old behind the Taif accord, Mr Brahimi went on to lead UN mediation efforts in numerous parts of the world, most recently in Syria.

Initially, the Syrian opposition team at the Geneva talks worried that he would pursue a deal that perpetuated the dominance of Al Assad’s Alawite minority. But he resigned in 2014 after two years, citing the intransigence of the regime.

In the end in Syria, Mr Brahimi refused to make a deal at any cost, something many Lebanese wish he had also done for them 30 years ago.