Lebanese from many walks of life sank into economic despair this week as the currency hit new lows, dealing sharp blows to incomes.

A financial meltdown in Beirut is behind the renewed collapse of the Lebanese pound, which started in October.

“Lebanon will not last to the autumn,” read a headline in leading Beirut daily An Nahar.

Data by currency monitor lirarate.com showed the pound, also called the lira, trading at 9,000 to the US dollar on Wednesday.

It was trading at 4,000 pounds to the dollar at the start of June, and about 1,500 to the dollar, the official and now mostly nominal peg, in October.

Talin Kanledgian, owner of Jasmin Parfumerie in Beirut, said buying essential goods and services had become frightful, because most prices keep rising.

Basic staples, fuel and medicine are subsidised. But this week, the government increased bread prices by a third, raising fears that the rest of the subsidies could go.

“If you go to the supermarket you will start crying. Everyone I know is depressed,” Ms Kanledgian told The National.

When she wanted to replace the worn tyres on her Mitsubishi Lancer a few days ago, she was astounded to learn it would cost her 2.5 million pounds.

They had cost 400,000 pounds before the financial crisis started in October.

Each sum, then and now, equates to $270, or Dh991.

She could get them for the old price if she pays in dollars, because the tyres are old stock.

But capital controls imposed in November prevent access to foreign currency deposits.

At her Hamra district shop, established by her Armenian father in the early 1970s, Ms Kanledgian has been discounting stock bought before October to try to boost sales.

She expects a mass departure from Lebanon now that Beirut airport has reopened.

Flights leaving the country had been halted because of the coronavirus. “Those with second passports or properties outside Lebanon want to leave,” Ms Kanledgian said.

A Lebanese surgeon who holds a French passport said he was considering going back to France, where he studied and worked.

“I don’t want to leave again but I have a family to look after,” he said.

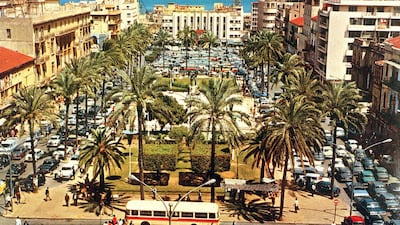

The surgeon is one of large numbers of Lebanese who joined the diaspora during the civil war between 1975 and 1990, returning after Lebanese statesman Rafik Hariri embarked on rebuilding the country. Hariri sought to restore prosperity and maintain the open society that had distinguished Lebanon for decades from the rest of the non-oil countries of the Middle East.

Under his vision, Lebanon partly re-emerged as the playground of the Middle East and a financial centre.

But he largely stayed away from tackling corruption.

Hariri believed Lebanon's sectarian political system and the influence of the Syrian regime made corruption inevitable. Instead, he strived for economic growth to overcome Lebanon's inefficiencies, and contradictions.

But public debt, first accumulated by Hariri, steadily rose to one and a half times GDP.

A peaceful uprising demanding the removal of the entire political class broke out in October last year.

The movement forced the resignation of Hariri’s son, prime minister Saad Hariri.

But the political class united against the uprising and a government closely aligned with Hezbollah took over in January.

By April, the authorities had all but crushed the protest movement with the help of the army, a popular employer in Lebanon. Many young Lebanese, even those from middle-class backgrounds, choose to join the army because of the salaries and perks.

Army personnel typically retire in their early forties with savings and connections that set them up well to embark on a second career in the private sector. But earlier this week, official media announced that to save costs the Lebanese army had "completely scrapped meat from meals offered to on-duty soldiers".

Youssef Chahine, a young Lebanese supporter of the uprising, said the currency collapse made soldier's salaries equal to only $110 a month.

“Let’s see if they keep beating up protesters,” Mr Chahine said.

The lira briefly stabilised at about 4,000 to the dollar last month, as the government started talks with the International Monetary Fund for emergency rescue.

But Alain Bifani, a finance ministry official and a top member of the government negotiations team with the IMF, resigned this week.

Mr Bifani said he was fed up with the whole political class's handling of the financial crisis. He was the second member of the Lebanese negotiating team to walk out.

Confidence is so low that the World Bank two weeks ago denied rumours picked up by local media that it had predicted Lebanon would collapse.

The World Bank said it supported Lebanon’s “efforts to address the social, financial and economic challenges it is enduring”.