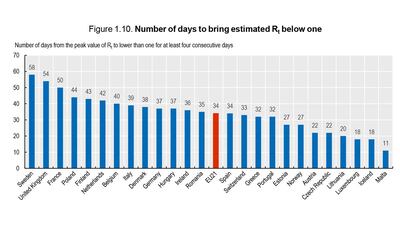

Britain took 20 days longer than the rest of Europe to halt the first wave of coronavirus, according to a new report.

Sweden, which famously never ordered a lockdown, was the only other European country to fare worse than the UK.

The assessment was contained in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Health at a Glance Europe 2020 report.

The study compared data from across the continent to show how each country responded to the initial outbreak beginning in March.

Sweden took 58 days to bring the R rate, the number of people an infected person goes on to infect, below 1.

The UK, which issued a stay at home order on March 23, brought the virus under control just four days earlier.

France took 50 days, while Poland and Finland took 44 and 43 days, respectively.

Hard-hit Italy took 39 days to halt the first wave - measured as achieving four consecutive days of the R rate below 1.

Malta was able to bring its R rate under control the quickest in just 11 days, followed by Luxembourg and Iceland, achieving it in 18 days.

The European Union average was 34 days.

The report found measures such as banning large gatherings, encouraging people to work from home and mask-wearing were significant in reducing the spread of the virus.

Also a factor was the speed in which countries reacted to initial outbreaks.

Countries that delayed imposing lockdowns fared worse than those that acted early, the study found.

For example, nations that closed public places two weeks before they hit 10 deaths per million brought the virus under control in an average of 30 days, compared with 39 days for countries which were slower.

In the UK, the Cheltenham races and a Liverpool football match in the weeks before lockdown were among the spectator events linked to known outbreaks.

The OECD study also found Italy’s health system came under the biggest strain in Europe.

Up to 78 per cent of ICU beds in Italian hospitals were occupied by Covid-19 patients during the first wave.

Ireland, France and Belgium all had more than two-thirds of ICU beds taken up by coronavirus patients.

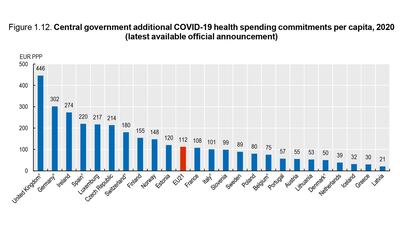

On government spending, the UK has splurged nearly €450 (£400, $534) per person responding to the pandemic, adjusted for purchasing power parity.

In Germany and Ireland, health budgets received a boost of about €300 per person.

Spending averaged under €50 per person in Latvia, Greece, Iceland and the Netherlands.

The majority of funding went to procurement of personal protective equipment, testing, recruitment of healthcare staff and contributions to vaccine development.

Meanwhile, the World Health Organisation (WHO) says Europe’s painful second wave may be starting to ease but the death toll remains stubbornly high.

Hans Kluge, WHO’s regional director for Europe, said coronavirus patients were dying every 17 seconds across the continent.

New infections slowed to 1.8 million new cases, compared to 2 million the week before.

Mr Kulge said the drop was a “a small signal, but it’s a signal nevertheless”

“There is good news and not so good news,” he added.