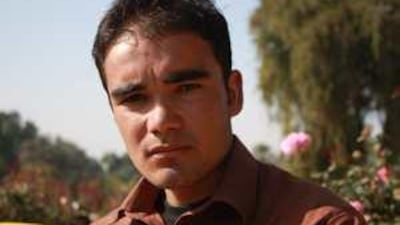

Farid Ahmad Naseri grimaced and as he tiptoed around the ankle-deep pools of mud littering Kabul's winter streets. "I cannot live here any more, I must go back to Britain," he said, as he looked at the potholes filling with filthy rainwater.

A fortnight earlier, Farid had been marched onto a UK Border Agency charter flight by security guards at Heathrow and deported to Afghanistan along with 30 of his countrymen. The flight ended a journey that had seen him sell land and borrow money to risk his life at the hands of people smugglers, who promised he could claim asylum in Britain. After spending months trekking across Asia and Europe, witnessing fights and a murder, he was arrested on his first day in Britain. Although he escaped from detention, he was arrested a second time, locked up and sent home.

He was back in Kabul nearly 18 months after departing and US$15,000 (Dh55,000) poorer, but the promise of the West remained a tantalising solution to his problems. "At the moment, I don't know what I should do," he said. "I don't have enough money. I am very confused why they didn't look at my case, they didn't let me apply, they just sent me back. "But I would very much like to go back there." About three times a month, a charter flight disembarks tired, dishevelled young men like Farid at Kabul international airport after an 18-hour flight from Heathrow via Azerbaijan.

Last year, an estimated 700 young men were forcibly returned from the UK after their asylum claims were rejected or they were found working illegally. Many more volunteered to come back with a package of up to £5,000 (Dh29,000) to restart their lives. Farid said he needed to claim asylum after being persecuted because of his uncle, Amar Anwar, whose name is still spoken of bitterly in the Shomali plain north of Kabul.

A former ally of the Mujahideen leader Ahmad Shah Massoud, Anwar fell out with the legendary commander and sided with the Taliban in the mid-1990s as fighting spread across the plains north of the capital. Anwar was never forgiven by the Shomali Tajiks and his relatives were fair game for reprisal and vengeance, Farid said. Coupled with that were his grim prospects eking out a life on $4 (Dh15) a day as a taxi driver in a Toyota Corolla.

"We had problems in our village with our enemies because of my uncle and also it is difficult to live in Afghanistan." His planned escape was behind crates in a lorry via Iran, Turkey and Greece in a six -month odyssey across continents. Passed from one trafficking gang to another, he lived in fear of robbery or violence. "Sometimes there were people fighting with knives," he said. "One night a gang of rival smugglers attacked us and tried to destroy our tent. They killed one of our smugglers."

Farid eventually made it to Greece where he registered to seek asylum and was put on a waiting list. From there he travelled to France where he spent six weeks living in the notorious "Jungle" of makeshift tents and shelters in Calais, before he was able to climb into the back of a lorry headed to Dover. When he clambered out on British soil, he was spotted and arrested and put into temporary accommodation. Fearing he would be sent back to Greece for processing he fled the accommodation but was later seized for a second time, when he was found working illegally in a Manchester greengrocer.

British immigration authorities locked him up until he was deported. Dog-eared immigration papers, which he cannot read, explained he had been thrown out for escaping from his accommodation, not giving satisfactory answers and failing to comply with his temporary entry conditions. Since returning to Afghanistan, he said, fear of his enemies had caused him to hardly venture from his house. Britain remains one of the most popular destinations for Afghans seeking asylum or work. Many have learnt English at school and feel they are unlikely to stick out in the multicultural cities.

According to the recent British government figures, 3,505 Afghans applied for asylum in 2008, up more than a third from the previous year, but down from the 2001 peak of nearly 9,000. Under the 1951 United Nations convention governing refugees and asylum, successful candidates must have "a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion".

Of 2,340 asylum rulings made in 2008, four per cent were successful and another 38 per cent were allowed to stay temporarily on health or humanitarian grounds. Fifty-eight per cent were refused. Of those claiming asylum in 2008, 1,740 were under 18, but border officials claimed that in more than 550 of those cases the claimant lied about their age in order to help their application. Mohammad Malakhal, another Afghan who had fled his country for Europe fearing for his life, is now back in Afghanistan after being deported and worries for his safety.

His father, Bismillah, a former local commander with Hizb-i-Islami, a powerful insurgent faction aligned with the Taliban, was killed fighting the government five years ago. Mohammad had unwittingly delivered Hizb-i-Islami propaganda leaflets for his paternal uncle, Shah Mahmoud, until the local police heard of his work and began intimidating him. "I distributed leaflets and the police came to see me five or six times," he said.

"I didn't know about them, I hadn't read them, I didn't open them, I just distributed them." After again selling land and borrowing money to raise $10,000 (Dh37,000) for a people smuggler, he had left his home in Jalalabad, in eastern Afghanistan and travelled in the back of a lorry via Iran and Turkey. But not long after arriving in Britain he was arrested in Coventry when police found him sleeping in a park. He spent eight months in a hotel with other Afghans while his application and appeal were rejected.

"They said I was lying," he said sullenly, sitting in a park in Jalalabad a month after his return. "They said I should bring proof, but I didn't have any documents and I didn't have any friends or relatives who could help." Since returning, Mohammad said, he had lost his family and was feeling threatened, but was evasive about how he was living and where his family might be. "I have no money and I have no family," he said.

"Sometimes I feel like I want to kill myself. If I had the money, I would try and get back [to Europe]." One asylum lawyer working in London, who did not wish to be named, said Mohammad's story was common. "I or my colleagues hear the 'I was delivering leaflets for my uncle' story several times a week," she said. One western official in Kabul said anecdotal evidence suggested trafficking gangs coached their clients on what to say as part of their service. The higher the fee, the better the cover story and more evidence.

He said: "We hear if you pay $200 you will get a core script that says everything you need." Once back in Kabul, there is little information on what happens to those forcibly returned or whether the fears presented in their asylum claims are realised. The British government said there was no evidence of any returnee being persecuted or killed, except one who had been the victim of criminals who assumed he had made a fortune in Britain.

However the Refugee Council in London said no one really knew if they were in danger or not. Hannah Ward, a spokeswoman, said: "There's no monitoring of what happens to people who return, so it's slightly disingenuous to make the argument that there is not evidence of anyone being persecuted. "If they are saying we don't know if they are going to be in trouble, that's worrying in itself. "I don't think there are many people who would be happy with the idea of us just washing our hands of these people."

With violence increasing in Afghanistan, forced repatriation has become a sensitive issue. The United Nations estimated more than 2,000 Afghans were killed in fighting last year, mainly in indiscriminate Taliban bomb attacks or executions aimed at those working with the government. At the same time, one international official in Kabul said countries including Britain, Sweden, Norway, Belgium and Germany were under pressure to convince their voters progress was being made in Afghanistan.

"It's actually a very small number being sent back from some of these countries, but it is politically important," he said. "We are spending a fortune here and we are supposed to be making progress. They don't want to be taking people because it looks like our efforts are not working." * The National