The ancient Silk Road was a trading network that connected civilisations. Roman, Greek, Arab and Indian merchants, among others, worked their way along the route.

Goods, such as coveted Chinese silk, were traded, alongside culture, technologies and philosophies.

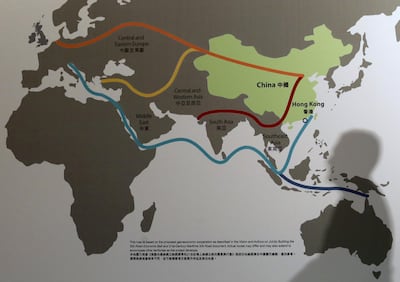

China now looks to the future while seeking to resurrect past glories with its Silk Road Economic Belt and the Maritime Silk Road, together known as the One Belt and One Road initiative (Obor) or the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). More than 60 countries and international organisations have signed up for the infrastructure project.

From Russia in the north to Myanmar in the south, and across to western Europe, the land-based BRI covers a vast expanse of the Earth. The accompanying Maritime Silk Road will include Singapore and ports along the Indian Ocean, including in east Africa, and Oceania.

The Silk Road Economic Belt and Maritime Silk Road were announced in September and October 2013, respectively, and many countries along the routes have signed up to the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.

Projects such as the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), estimated to be worth US$60 billion (Dh220bn), have been subsumed into this overarching strategy that many analysts believe is China's bid for global influence.

But there are challenges as China looks towards Eurasia to extend its influence, with rivals such as India, Japan and Russia warily eyeing their increasingly assertive and ambitious neighbour.

Many projects

The BRI projects are numerous but focus mainly on infrastructure, transportation and energy. These include the already completed rail route transporting goods from the trade centre of Yiwu, in eastern China, to Madrid, the Spanish capital.

The Karot hydropower project in energy-starved Pakistan, due for completion in 2020 and financed by the China-founded Silk Road Fund, will be a key indicator of China's ability to deliver large hydroelectric plants internationally.

Oman, with China's help, intends to build an entire new city on its coast, 550 kilometres from Muscat. The $10.7bn project seeks to transform the remote seaport of Duqm into a major hub of global trade and manufacturing. Long-term plans include an array of industrial capabilities such as an oil refinery and a multibillion-dollar methanol plant, among much else within the Duqm Special Economic Zone, as well as a $200m five-star tourism zone.

In Abu Dhabi, a $300 million deal was signed between China's Jiangsu province and Abu Dhabi Ports to develop a manufacturing operation in the free trade zone of Khalifa Port.

In the Indian Ocean, China has just been handed a 99-year lease of Hambantota port from indebted Sri Lanka, which sparked protests over what political opponents saw as erosion of sovereignty.

North-west of Sri Lanka and India, Pakistan is the recipient of much Chinese investment. China wants to turn Gwadar, on Pakistan's southern coast, into a megaport. Plans include building export-focused industries within special economic zones, and a network of energy pipelines and rail and road links that will connect Gwadar to China's western regions.

China has pledged half a billion dollars in grants to turn deprived Gwadar into what Islamabad and Beijing see as the jewel in their co-operative plans. Of this, $230m is set aside for a new international airport and the remainder will be spent on much-needed water infrastructure, a hospital and a technical college.

In Central Asia, China has built a dry port in Kazakhstan, turning what was once a barren plain into the Khorgos Gateway — a new cargo terminal for east-west freight trains. Pipelines for gas are already laid across the "Stan" countries, while high-speed railway lines linking western China to Iran are in development.

Setbacks

However, BRI projects have faced setbacks. In Pakistan, China was set to finance the building of the $14bn Diamer-Basha dam on the Indus river but Pakistani officials balked at the conditions for funding, including China gaining ownership of the entire project. Pakistan is proceeding with the dam, a part of the CPEC, but will build it alone.

China also faces competition from regional rivals India and Japan, who have pledged to deepen strategic ties. They two countries have held joint military exercises and even have their own grand initiative, the Asia-Africa Growth Corridor. India, however, lacks the capital to compete and focuses mainly on investments in south-east Asia and Iran, leaving Japan to be China's main rival in overseas infrastructure development in Asia.

For south-east Asian countries seeking investment for infrastructure projects, their political considerations will have to weigh the pros and cons of either cosying up to Tokyo or to Beijing, and the political consequences of each.

Another concern, at least for China's partner countries, is whether BRI projects will have real economic benefits. For countries who have handed over key assets, such as such as Sri Lanka and Hambantota port, Chinese investment came at a huge cost. Other countries will pay attention to such cases, and in Pakistan officials chose to go it alone in the case of the Diamer-Basha dam rather than hand over control.

Grand foreign policy

For president Xi Jinping, China's strongest leader in decades, the BRI is his defining foreign policy strategy, the broad intention being the extension of China's commercial reach and political influence. Bringing Europe and Asia into a tighter, more cohesive trading network, with China as the focal point, also challenges the dominant US view which sees Europe and Asia as its backyards.

Although ambitious, the BRI has as much to do with domestic economic and political concerns as it does with global strategy and at its core seeks to stabilise control for China's Communist Party. Like many national-level initiatives the BRI is grand but also pragmatic, and bankrolled with huge funds.

Domestically, BRI allows Mr Xi to cement control of the country's massive state-owned enterprises and industries. With a decreased interest in domestic building, BRI projects give China's industrial sectors the opportunity to refocus their excess capacity. Beijing also requires provincial-level companies to apply for loans for regional BRI projects, seeking approval from the party, thus increasing centralised control.

With the huge intercontinental scale of the BRI, Mr Xi will want to see China as a greater force in the future, exerting its influence with hard and soft power over an extended domain. But whether the initiative will achieve such an ambitious goal depends on factors perhaps beyond Beijing's control.

One of these factors is Russia, which has historically seen itself as the dominant player in Eurasia. Although Vladimir Putin has been warm in public towards the BRI, many in the Russian president's court regard China's growing presence in central Asia with wariness. Despite a reported personal affinity between Mr Putin and Mr Xi, the two leaders have very different approaches to their goal of attaining great power for their countries.

Moscow pays attention to economics but uses a variety of tools to influence geopolitics. Beijing on the other hand sees economic growth as the primary tool with which to win status, and the BRI is firmly within that strategy. But in order to safely continue its central Asian investments China will need Russia's backing or at least its acquiescence, according to Yu Jie, author of a report titled China's One Belt, One Road: A Reality Check for the London School of Economics' foreign policy think tank, LSE Ideas.

In the report, Ms Yu outlines long-term challenges for the plan. She compares it to the post-Second World War Marshall Plan, the US-led economic initiative that helped to restore many of its allies' battered economies and enabled the US to develop a global network of allies with similar governments — liberal democracies — and values. But the BRI does not seem to have a vision beyond the harder economic motivation of "win-win", Ms Yu believes. Many of the countries within its range also have issues with governance, security and ethnic conflict that may put investments at risk in the long term.

Ms Yu concludes that for China to improve its global diplomacy, and thereby become more influential on the world stage, it will need to draw on policies that "go beyond the simple purposes of securing China's own economic interests". She suggests that greater transparency, and a greater willingness to take interest in its partners' wants, needs, and desires, might prove beneficial.

With about $900bn earmarked for BRI projects in 60 countries, China's centrepiece foreign policy strategy is certainly not short of money or ambition. But whether it will draw those countries closer to Beijing's way of thinking remains to be seen.

Just what is Beijing's way of thinking? Is it simply a world where China is, as it has seen itself in the past, the Middle Kingdom, the centre of the world? And how will that benefit other countries?

These questions may at some stage have great consequence as China buys it way towards global influence.

________________

Read more:

ISIL defeated - but not a lot else to boast about for Trump in 2017

Money year in review: Despite doom predictions, the upward trajectory continues

Year in Review: Populism was on the march in 2017

________________