It was once called the Village of Bitter Gourds for the vegetables that residents grow in Chut Pyin. As well as the gourds, the lush fields around their homes in northern Rakhine State produced a profusion of rice, pumpkins and okra.

But last year, the rice paddies of Chut Pyin became killing fields, as Myanmar soldiers and Buddhist extremists carried out a brutal massacre of the Rohingya villagers. On August 26, nearly 400 of them were killed and the village razed, while those who survived fled on foot across the border into neighbouring Bangladesh. The bitter gourds of Chut Pyin were supplanted by bitter memories for the more than 1,000 odd people to whom that bountiful home is just a memory.

Instead, 12 months on, the villagers live in a tight cluster of tarpaulin and bamboo huts atop a small hillock in the Kutupalong-Balukhali Refugee Camp.

"You won't find anyone around here who didn't lose at least one family member," says Mohammed Sadiq, a grey-haired farmer in a white skull cap, whose granddaughter and daughter-in-law were both killed.

Of the 1,400 Rohingya who lived in Chut Pyin, 358 were killed and another 94 were wounded, according to Ahammed Hossain, who was once the village foreman.

According to Mr Hossain, a boyish 25-year-old who wears a T shirt emblazoned with the white sign of the Hollywood hills, a further 59 men were detained by Myanmar soldiers and have not been released. At least 19 women were savagely raped. He recounted how he found his own sister dying in the bushes after being raped and shot.

"I couldn't save her," he says flatly. His father and brother were also killed, he added, the numbness of loss palpable in his voice.

The massacre at Chut Pyin – which has been documented and corroborated by various international rights groups – became the most notorious example of the Myanmar government's campaign to expel the ethnic minority Rohingya from its lands, and precipitate a mass exodus of refugees into Bangladesh.

Today, as Bangladesh and Myanmar discuss the return of refugees, the villagers of Chut Pyin hold up their experience as evidence of why greater international involvement is needed to protect the rights of Rohingya Muslims.

____________

Read more:

UN Security Council urges Myanmar to ease Rohingyas' safe return

Bangladesh deploys police after Rohingya camp killings

UN chief: military grip on power key obstacle in resolving Rohingya crisis

Rohingya tell UN chief of ‘unimaginable’ atrocities in Myanmar

____________

An investigation by Physicians for Human Rights, a Boston-based non-profit, published last month concluded that "the savagery inflicted on the people of Chut Pyin is a typical example of the widespread and systematic campaign that Myanmar authorities have waged against the Rohingya – acts that should be investigated as crimes against humanity".

Before last year's bloodshed, communal hatred had been simmering for decades in Rakhine state, where ethnic Rohingya Muslims lived alongside Rakhine Buddhists.

Myanmar's Buddhists – who account for almost 90 per cent of the population – nevertheless feared that Muslims could usurp them. What resulted was a portrayal of the Rohingya as Bengali interlopers living illegally in the country. Some 120,000 Rohingya already lived in guarded displacement camps inside Myanmar, and another 400,000 in exile in Bangladesh.

The massacre at Chut Pyin came directly after a rag-tag Rohingya militant group called the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army carried out attacks on Myanmar border guards. Afterwards, the Myanmar government explained the deaths at Chut Pyin and elsewhere as the result of counter-terrorism operations.

Over the months that followed, some 700,000 Rohingya fled across the border, in what the then UN human rights chief Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein described as "a textbook example of ethnic cleansing" by the Myanmar government.

In such a densely populated, low-lying country as Bangladesh, the only land available for the Rohingya to shelter was a national forest, a southeastern landscape of low hills and meandering waterways abutting verdant paddies.

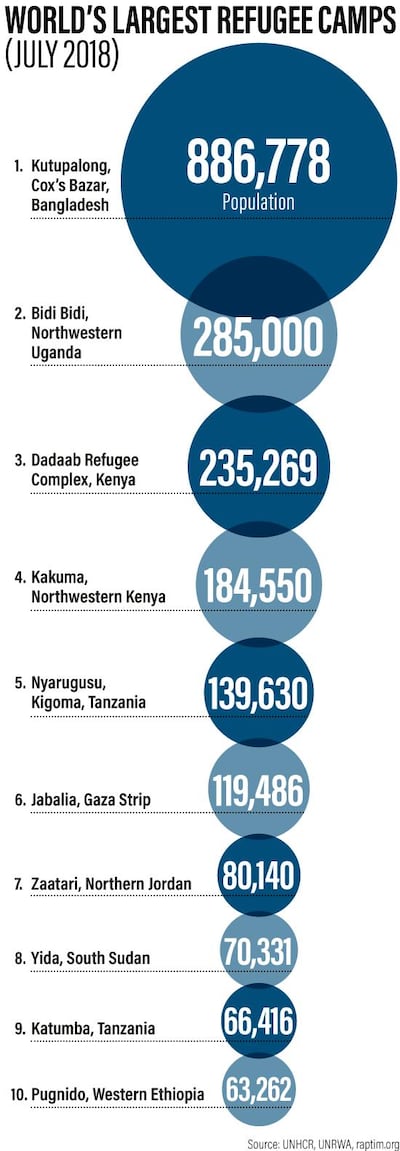

The camps sprung up haphazardly, with aid agencies struggling to install sanitation and drainage and warning of the risk of massive disease outbreaks. A year on though, what was jungle is now a conglomerated "mega camp", the world's largest refugee settlement.

A sprawling site that stretches for miles, the camp consists of tight rows of huts jostling for space along the contours of the hillsides. Paths are swept clean, huts kept trim, and tiny vegetable allotments planted on any level foot of bare ground. Informal markets have sprung up along the roads, where industrious men sell dried fish, vegetables and neat bundles of firewood, each stick cut to the same length. Amid their desperate situation children remain children, playing under the well pumps and toy cars crafted from discarded plastic and sticks.

But with every monsoon rain, the sandy soil of the hillsides slowly subsides, collapsing homes and destroying paths. Work crews dig continually to terrace and stabilise hillsides at risk of collapse. When cyclone winds blow, roofs fly off huts. Keeping the latrines sanitary and the water from pooling takes constant work.

Throughout its makeshift lanes, the villagers of Chut Pyin somehow stoically ward off despair, but as time passes their situation is becoming more desperate.

Outside the camp, the movement of refugees is restricted and they cannot work legally. Children are not allowed to be formally taught either the Myanmar or Bangladesh curriculum.

As such, life is on hold. A sense of alienation has grown out of them not having any acknowledged status.

While the Bangladesh government has welcomed the refugees, it remains acutely sensitive to the idea of Rohingya being given any permanent right to remain. The Myanmar government has thus far refused to recognise them as an ethnic group. As a result, in the camps they are identified neither as refugees nor Rohingya. United Nations issued ID cards identify them as "forcibly displaced Myanmar Nationals".

In talks – which have not included the Rohingya themselves – the Bangladesh and Myanmar governments have agreed that repatriation should be done in a voluntary, safe and dignified manner. But without guarantees of citizenship and some form of international protection, most Rohingya say they are unwilling to return.

"Our future depends now on the international community," says Mohammed Rafiq, a 23-year-old farmer left lame by a bullet wound. "I want citizenship rights and I want our security guaranteed, when we get this we will go home."

After all that they have been through, being left in limbo could be the cruellest blow.

Salim Ullah, 26, ran from his home when the soldiers came to the village. When they saw him flee they fired at him.

"After I was shot I hid from the soldiers in a cesspool. I saw them with our women, doing whatever they wanted.

"We lost everything then," he says. "But now we're losing hope too."