SYDNEY // Johnny Lovett's father, Herbert, fought in two world wars, although as an Aboriginal man he was not recognised as an Australian citizen. But when he came home, he was "back to being black" - unable to vote, buy property or marry a white woman.

And while his white comrades were given land to farm by the government, Herbert Lovett received nothing. He and his family had to live off the meagre wages he earned labouring for others on the land his ancestors owned before European settlement.

Nearly 70 years on, Johnny Lovett remains outraged by the way his father, along with many of his other male relatives, was treated. Herbert was one of four brothers to fight in both world wars, and altogether 21 Lovetts served their country in theatres of war, including Japan, Vietnam and Korea. In fact, the family, from rural Victoria, has a service record believed to be unrivalled in the British Commonwealth.

Now Johnny is battling to persuade the government to rectify what he calls a "very big moral wrong". He wants compensation for the land on which others grew rich, and for the opportunities which his family - condemned to a life of hardship and poverty - missed out on. His father "gave so much and got so little in return", said Mr Lovett, 64.

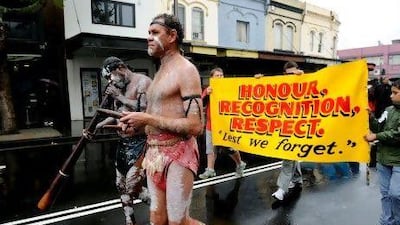

Nearly 5,000 indigenous men and women volunteered to fight abroad in the two world wars, but their contribution has yet to be fully recognised. Their names are missing from the war memorials found in nearly every Australian city and country town, and from the history books. Returning home, some bedecked with medals, they faced the same discrimination as before.

For Johnny Lovett, their exclusion from the "soldier settlement" scheme - under which blocks of land were made available for demobilised soldiers to buy or lease - rankles the most. His father and uncles were forced to watch as the Lake Condah area of south-western Victoria - land which belonged to their Gunditjmara language group before Australia was colonised - was divided up among white veterans.

In the mid-19th century, the Lovetts were known as the "fighting Gunditjmara" - they fought a 22-year war against white settlers. Later, they and other Aborigines from the area were confined to a mission by colonial authorities. Paradoxically, they then volunteered to fight on behalf of those who had taken their land.

"By then, Dad considered Australia as being his country, and if there was a threat to his country, he had to join forces with non-Aboriginal people to defend it," Mr Lovett said.

A machine-gunner on the Western Front, Herbert was joined in the First World War by four of his brothers: Edward, Leonard, Frederick and Alfred. When the Second World War broke out, all of them - apart from Alfred, who was too old - enlisted again, and were joined by their younger brother, Samuel. The four older men were assigned to garrison and catering units. All survived.

Hearing the Lake Condah Mission was to be included in the soldier settlement scheme, Herbert submitted and application for a block of land. "He never received a response," said Peter Seidel, a Melbourne lawyer acting for Johnny Lovett.

Mr Seidel is calling on the federal Department of Veteran Affairs to pay compensation. He notes that Herbert was able to join up in 1917 only because he had some white blood - then he was denied land because of his Aboriginality. "On any view, that is a very sad indictment on the state of Australian race relations over the period of two world wars," he said.

In the army, according to Johnny Lovett, his father "experienced an equality that he didn't experience in civilian life". It did not, however, extend to pay; Aboriginal recruits received one-third of the regular wage. And when Herbert came home, "he was back to being black", said Mr Lovett. Turning up in uniform, he and his brothers were refused service at the Lake Condah pub. One of them, Frederick, was so poor that his family lived in a tent.

Some things have changed. Aboriginal people finally became citizens in 1967. In 2000 the Canberra office block housing the Department of Veteran Affairs was renamed the Lovett Tower, acknowledging the family's extraordinary contribution to Australia's defence.

But it was not until 2007 that nationwide ceremonies were held to honour Aboriginal veterans. On Anzac Day, when Australia remembers its war dead, some indigenous old soldiers - who feel alienated from mainstream events - hold separate marches.

Meanwhile, the Lovetts have continued to distinguish themselves. Johnny Lovett was one of four men who fought a successful Federal Court action to secure "native title" over Gunditjmara traditional lands, where they can now camp, hunt and fish. Iris Lovett-Gardiner, Frederick's daughter, was awarded a doctorate in her early 70s for a thesis on the Lake Condah Mission.

Nathan Lovett-Murray is a professional Australian rules footballer with Essendon, a leading team. Ricky Morris, Frederick's grandson, served with Australian peacekeeping troops in East Timor.

foreign.desk@thenational.ae