Dozens of horses and their riders gathered under the snowy foothills an hour outside of Kabul on a winter day earlier this year. The horses bucked and brayed as the riders eyed each other in anticipation. The riders were armed with whips and armoured in thick woollen layers, old soviet tanker helmets and the occasional turban. After a quick prayer they were off.

The ground trembled as the horses charged towards a calf carcass lying in the centre of a ring 150 metres across. The riders whipped, yelled and cheered. As mud and snow were kicked up from the scrum of horses, one rider Najibullah Pahlawan reached out and lifted the carcass up and over his saddle. All he had to do now was ride with the carcass around a flag a 100 metres away and bring back to the starting line and he would score. This is buzkashi.

Afghanistan’s national game, whose name translates as “goat pulling” in Dari, has enjoyed a resurgence since the fall of the Taliban. Some in the country now fear though that if the fundamentalist group were to return to power, the fate of their beloved game could once again be under threat.

Buzkashi originated sometime between the 10th and 15th centuries with nomadic tribes in central Asia. The game was widely played in Afghanistan until the Taliban regime came into power in 1996 after a brutal civil war that followed the Soviet occupation. The Taliban then banned the sport, alongside kite flying, music playing, women’s education and anything else the hardline group considered un-Islamic.

After 17 years of war, the US has finally entered into negotiations with the group it overthrew back in 2001. It is unclear the extent to which the Taliban has moderated its views but it seems likely it may return to some form of power in the country.

The insurgent group has claimed they have reformed and will allow certain things that were once banned during their short lived rule in Kabul, including allowing women to receive an education as long as it keeps within their interpretation of Sharia law. However, no clear statements have been made about what specific sports will be allowed. In the past though certain factions within the Taliban gave tacit approval to the playing of buzkashi.

But the Taliban has also at times seen time gatherings at sports venues as soft targets. Since 2001 the group has claimed several high-profile attacks at buzkashi matches. In January of 2017 an explosion following a buzkashi match in the northern province of Balk killed a local anti-Taliban militia leader and his body guards as spectators were leaving the match. In 2013, a suicide bomber attacked another match in the north, this time striking Kunduz province which shares a border with Balk, killing at least seven.

Rugged buzkashi players like Najibullah, who are known as chapandaz, say they will continue to ride, irrespective of the Taliban’s view of the game. “I am not worried about the Taliban, they liked buzkashi,” he said. “I don’t worry about it.”

During the Taliban’s rule, some commanders were happy to flout official rules to allow matches to happen openly. “Not in Kandahar,” said Najibullah, referring to the southern city located in Taliban heartland, “mostly in the north.”

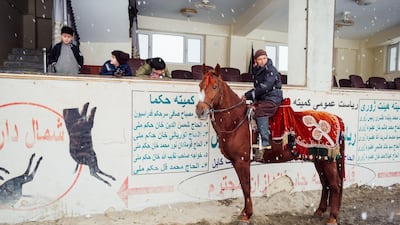

Growing up in the northern province of Samangan where the sport is popular, Najibullah would see matches with over a hundred horses on Fridays and during special occasions when matches would be held to celebrate events. Najibullah, now 30-years-old and married, practices twice a week and has sponsorships from various companies around Afghanistan. Some of his sponsors provide him with horses imported from Russia, Tajikistan and Kazakhstan, which can cost up to $50,000 (Dh183,655) depending on its size and speed. “I have my own horse that I keep in my home, but my competition horses are in stables that the sponsors own,” he said.

Najibullah is now a three-time champion of the sport, having competed in national and international competitions. He rides for the Afghan national team and is locally famous but still farms wheat during the off season.

During buzkashi season, matches commence after Friday prayers and usually draw a large crowd ranging from a few hundred to a few thousand depending on where the match is held and the weather. After several hours of play the match becomes a sudden death style tournament, where whoever scores the last goal is declared the overall winner.

By this stage in the recent match outside Kabul the snow was trampled into mud and a cloud of condensation had formed over the exhausted horses and riders. This point of the match is most intense for both rider and fan.

“Every horse represents a wealthy man, it’s exciting to see whose horse will win, whose rider is the best,” said local fan Elyas Saleh, a 28-year-old from the northern Jowzjan province.

After the final score, the rider receives the accolades of the crowd.

“When a rider finally wins and shows off his riding skills, for that moment, he is the champion,” says Mr Saleh. “Everyone wants their favourite to win and when he wins, we win.”

After hours of riding and competing Najibullah had scored several times. For each goal he would make he’d win a few hundred Afghani or roughly a couple of dollars. As the match drew to a close he scooped up the carcass one last time, trampled and torn it would only have to stay intact just a few minutes longer. He rounded the flag and raced back against all the other chapandaz and dropped the calf in the goal.

“Everyone looks and thinks, there goes the champion,” he said. “And I am the champion.”