For three centuries, the Roman leader Sponsian, who was first discovered on a set of coins found in Transylvania, was believed to be fake. Unearthed in 1713, the coins depicted him as an emperor — but in the absence of other information, the unconventional coins were widely dismissed as forgeries.

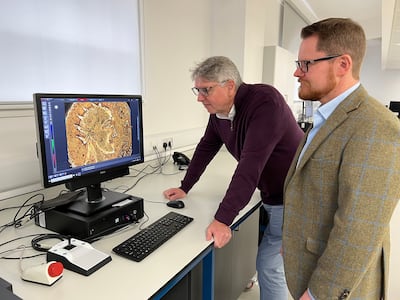

However, a new study on four ancient gold coins from The Hunterian collection at the University of Glasgow and the Brukenthal National Museum in Sibiu, Romania, has revealed that not only were the coins authentic, but they shed light on an obscure figure, and his role in the Crisis of the Third Century.

Professor Paul N Pearson, professorial research associate at UCL's Earth Sciences department, who led the project, says it began during the first Covid lockdown in 2020. “During the first covid lockdown, I decided to write a new history of the Third Century crisis in the Roman empire, which began with a viral pandemic in 248 AD and was a time of anxiety, economic decline, inflation, political instability and war, so seemed grimly appropriate.”

His book, The Roman Empire in Crisis, 248–260: When the Gods Abandoned Rome, spans a period of time when the Roman empire was overrun with civil strife and rebellion, as successive leaders attempted to seize power for themselves, only to be murdered and overthrown.

“The empire suffered a series of escalation disasters until it broke into warring chunks around 259-260 AD,” Pearson tells The National. “I came across the story of the 'fake emperor' Sponsian while researching this — ‘fake’ because he is known only from coins that were pronounced fakes in the 1860s and by every specialist since.

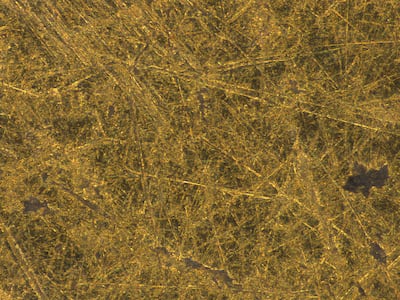

“I discovered one of the coins was in The Hunterian museum in Glasgow and asked the curator of coins and medals, Jesper Ericsson, for a photo for the book, as only grainy black-and-white images were available. Both of us were intrigued by what appeared to be wear scratches on the surface and dirt in the crevices among the lettering, so we decided to use modern scientific methods to decide if the coin really was fake or perhaps was authentic from the ancient world, despite being so unusual.”

The Sponsian coins are “extremely” rare, he says, with only four depicting him known to exist today. They form part of a larger group of unusual gold coins, which also feature the well-known emperors, Gordian III and Philip the Arab. Adding further confusion, two of the Sponsian coins feature mid-third century style on the front, with a reverse design copied from a Republican issue that would have been more than 370 years old at the time of manufacture.

“They are very obviously not of the high standard expected from the mint at Rome, instead they look distinctly home-made, and have been cast in clay moulds rather than struck between dies as was normal. So it is little wonder that experts have written them off as fakes,” says Pearson.

However, Pearson’s team concluded that rather than fakes, they were probably minted in the isolated province of Dacia — perhaps in the city of Apulum — by jewellery artisans, because the area had no regular coin mints at the time.

Europe’s richest gold field, Dacia had an abundance of gold and silver buried in its mountains, which was usually processed and exported to Rome as ingots — though this became increasingly difficult as the crisis deepened. Archaeological studies show that the area was cut off from the rest of the Roman empire in around 260 AD.

Encircled by enemies, Sponsian may have been a local military officer who was forced to step up and assume supreme command to protect the local military and civilian population until order was restored.

“At the same time, the flow of money from Rome dried up. The obvious thing for the stranded authorities to do would be to use the gold themselves and turn it to money. Gold was universally regarded as a high-value metal in Roman times as it is today and could be traded as bullion by weight.”

In Rome, coinage was also an important source of power and authority, and Sponsian may have authorised the creation of coinage to promote stability and support the economy of his isolated frontier territory.

Although little is known of who Sponsian was, the team has been able to draw some deductions from the coins themselves, along with “the very abbreviated historical summaries, and the fact they were found in Transylvania, in an area the Romans called Dacia”.

Pearson adds: “If our interpretation of the Emperor Sponsian is correct, he was a marginal figure for the history of the Empire as a whole and certainly never ruled in Rome. But he is of potentially of great interest for understanding the end days of Roman rule in Dacia, and for the history of Romania he might be a particularly interesting figure.”

Pearson says the biggest mysteries are why the coins are so deeply worn and only yet known locally.

“The best explanation, we suggest, is that they come from a time around 260 to early 270s, when the province became isolated from the rest of the Empire and the borderlands and neighbouring districts south of the Danube were devastated by invaders. The authorities in the province could have made their own high-value money to prevent rebellion and keep the self-sufficient money economy going.

"But this is just a hypothesis, and we would love to develop and discuss these ideas with historians now that our work is published.”

Scroll through images of 1,000-year-old coins discovered in Sharjah below