Finland's capital, Helsinki, has plenty of attractions for tourists, including a spectacular seaside fortress that is a World Heritage site, a former Olympic stadium and a wealth of Art Nouveau architecture.

From later this year, UAE travellers are likely to find that there is an additional reason to visit: cheap flights.

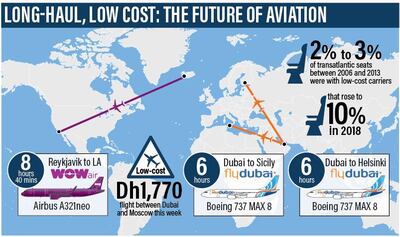

Low-cost carrier flydubai is launching services to Helsinki in October and, at more than six hours each way, it will be a long-haul flight. The airline already operates long-haul services to destinations such as Catania in Sicily, to which flights began in June and take fractionally more than six hours.

Just 2 to 3 per cent of transatlantic seats between 2006 and 2013 were with low-cost carriers, according to the UK-based consultancy Aviation Economics, but this year it is about 10 per cent. And these new destinations illustrate the growing ambition of low-cost carriers to do battle in the long-haul market, which, until relatively recently, was largely the preserve of full-service airlines.

Low-cost carriers have had a large short-haul market share for decades, but their long-haul services have only really taken off in large numbers in the past five years.

“It tends to be supply led. There were no long-haul, low-cost (LHLC) flights and people weren't banging on the door demanding it, but airlines started supplying it, which stimulated demand … There are plenty of markets where opportunities exist, and there will be growth in this sector,” said Jonathan Wober, an analyst for the Sydney-based market intelligence organisation CAPA – Centre for Aviation.

The first LHLC service was launched by Australia's Qantas in 2006, according to CAPA, with Malaysia's AirAsia X following a year later. Growth has gathered pace and there are now more than 15 LHLC airlines, some competing with one another on the same routes.

CAPA says that in 2017, for the first time, there were more than 500,000 LHLC seats each week, or about one in 200 flights. Now the figure is believed to be closer to one in 100. The growth has been helped by a number of factors, including upgrades in aircraft technology that have improved the business case for LHLC.

“Until a few years ago, you had to use different [aircraft] for short-haul and long-haul. Now you have extended versions of short-haul aircraft that allow the airlines to use the same aircraft for long-haul,” said Professor Andreas Papatheodorou, a professor of industrial and spatial economics with emphasis on tourism at the University of the Aegean in Greece.

Linked to this, the improved fuel economy of the latest aircraft makes LHLC more financially viable and could, CAPA suggests, create opportunities for new long-haul services by narrow-bodied aircraft on routes too “thin” for larger aircraft.

For passengers, there are significant savings to be made by flying LHLC. A return fare from Dubai to Moscow on flydubai, for example, leaving on July 13 and returning on July 18 (with checked luggage but no meals or in-flight entertainment), was listed as Dh1,774 on the company's website on July 5. The same day, the Emirates website's cheapest fare was Dh3,425.

Aviation Economics' analysis indicates that, last year, transatlantic flights on the low-cost carrier Norwegian were about $150 (Dh551) cheaper than those on full-service carriers.

Full-service airlines have responded by setting up low-cost subsidiaries offering long-haul services. Among them is Level, launched last year by British Airways' owner IAG, that offers long-haul services starting at an advertised €99 (Dh425). Singapore Airlines' Scoot took to the skies with long and medium-haul services in 2012, while Germany's Lufthansa offers LHLC flights through its subsidiary Eurowings. Air France has been doing the same with Joon, a low-cost subsidiary that was launched in December and has debuted new routes this year.

One function of such carriers could be to deter new LHLC operators from entering the markets of the established carriers.

“It's about pre-empting, making sure nobody else follows suit,” said Professor Papatheodorou.

Legacy carriers have started to also offer low-cost seats, where there might be fees for checked luggage and seat selection, on their standard long-haul flights. British Airways, for example, has introduced Basic Economy on selected flights; such initiatives have reduced the long-haul price differential between traditional and low-cost carriers.

Nevertheless, when running low-cost services, it may be harder to achieve sustained profitability in the long-haul market than in the short-haul sector.

Low-cost, short-haul airlines have undercut other carriers by flying into secondary airports, which have lower landing charges but typically are further from large cities. Aircraft utilisation has been significantly improved over traditional carriers, and pilots have worked longer hours, albeit within legal limits. Seat density has often been increased.

Such factors have helped the likes of Ryanair and Wizz achieve, said Tim Coombs, Aviation Economics' managing director, savings of as much as 50 per cent.

Short-haul, low-cost carriers secured “massive discounts” on aircraft because they have bought so many, but such discounts might be harder for LHLC carriers to secure.

“I would be surprised if Norwegian achieves a better price than British Airways for a [Boeing] 787,” said Mr Coombs.

“The legacy carriers are carrying a lot of premium traffic in first, business and premium economy and, to some extent, the economy seats can be cross-subsidised by the money they're getting from the premium cabins.”

On long-haul services, legacy carriers already have higher aircraft and pilot utilisation, because flights are longer. Opportunities for low-cost carriers to save money by using secondary airports may be more limited with long-haul than with short-haul.

Also, because fuel forms a larger part of the running costs on long-haul services, cost-cutting opportunities are further reduced. This helps to explain why few LHLC flights are longer than 10 hours.

CAPA's Mr Wober sees the LHLC model as yet to prove itself financially, citing Norwegian as an example.

“It's made two years of losses and two years of small profits. At best the jury is out on whether the model is capable of delivering sustainable profitability,” he said.

What can be seen as an alternative model has been followed by Sharjah-headquartered Air Arabia, which has a number of medium-haul services, including flights of more than five hours, such as to Sarajevo, and also has hubs away from its home airport.

________________

Read more:

UAE's cheaper flights plan for Indians seeks to make the Emirates a 'weekend getaway'

World's safest low-cost airlines 2018 revealed

________________

“They're trying to have a multi-hub strategy … To some extent they're trying to replicate the LHLC strategy by putting the flights together. They've established a subsidiary in Casablanca. You could fly from Casablanca to Sharjah, and from Sharjah to Nepal, by the same carrier,” said Professor Papatheodorou.

“As you have a low-cost carrier doing the connection, it's maybe the same effect as a LHLC service.”

Actual LHLC services themselves are still expanding in number, although whether this growth will continue is “a major unknown”, according to Professor Papatheodorou.

“If oil goes beyond $100 [a barrel], the cost advantage of low-cost operations vanishes,” he said.

“I wouldn't say it's reached a plateau, but I don't think it will grow as fast as it has in the past five years. In terms of percentage change, it will slow down a bit.”

Mr Coombs too has doubts about “whether they can really achieve lower costs to achieve the lower fares”.

“If Norwegian was to offer $99 fares, they could fill the aircraft up 10 times. The question is whether the cost base allows them to make a profit,” said Mr Coombs.

Nevertheless, with new LHLC routes still being launched, many passengers are happy to take the savings while they can.