It was almost nine decades ago that the author Aldous Huxley, in his famed novel Brave New World, created a society with genetically engineered citizens.

With claims emerging this week that twin girls with edited genes had been born in China, a first-of-its-kind for the world, Huxley's dystopian science fiction could be edging closer to becoming scientific fact.

The announcement by the Shenzhen-based researcher, He Jiankui, of the girls' birth has yet to be backed up by a scientific paper or to be reviewed by other academics, so there is no independent confirmation.

But his revelations has stirred up huge debate.

Speaking at a genome summit in Hong Kong on Wednesday, Dr He said he was proud of his work, revealing that he funded the experiment himself and that the twins - known as Lulu and Nana were born normal and healthy and added he plans to monitor their progress for the next 18 years.

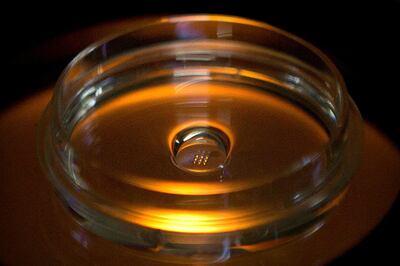

The gene involved in Dr He's work codes for a protein that allows HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, to enter cells; disabling the gene should confer resistance to HIV infection. In one twin, both copies of the gene were altered, while with the other twin only one of its two copies of the gene were affected, which may mean that the child does not have resistance.

Dr He also said that the study had been submitted to a scientific journal for review, though he did not name the journal involved.

Such a development could be seen as an almost inevitable result of significant improvements in gene-editing technology in recent years.

The reports have sparked significant reaction in the scientific community, much of it negative. China's National Health Commission has reportedly ordered an investigation and even the university where Dr He is a faculty member has condemned his work.

"We shouldn't go so far, this fast"

Among the scientists with concerns is Professor Thomas G. Jensen, a Danish researcher who is a member of his country's national science ethics board.

“If it's true then it's a major step and I think it's too fast, so I was surprised because I didn't consider that scientists would go this far so fast. I think it's too early; perhaps we should never permit editing of fertilized eggs and embryos,” he said.

There are many possible benefits of the technology, such as replacing “faulty” forms of genes that cause serious, sometimes fatal diseases. In theory, such illnesses could be eliminated not just in the individual born after gene editing has taken place, but in all future generations.

According to the California based non-profit organisation the Centre for Genetics and Society, this kind of gene editing affecting the human germline – the cells that pass their genetic material to offspring – is banned in more than 40 countries. China is not one of them, although reports say that government guidelines indicate that research embryos should not be used in reproduction.

Gene therapy, a separate technique in which individuals have genetic material delivered into their cells, often by a disabled virus, so that genes causing serious illnesses can be altered, is already used in a clinical setting.

Last year, UAE media reported on Khalifa Al Qemzi, a young Emirati child who had received gene therapy at a London children's hospital to strengthen his weak immune system, something thought to have saved his life.

With gene therapy, the patient's sperm or eggs are unaffected, so genetic changes are not inherited if the individual subsequently has children. By contrast, should either of the girls in China eventually become a mother, the offspring would inherit the altered gene.

Among the scientific concerns is the risk that changing a gene in one part of a person's genome may lead to unintended harmful effects; these could outweigh the intended benefits.

"It could create problems for the children in the future"

Prof Jensen, who is head of the Department of Biomedicine at Aarhus University, suggests that altering a gene that codes for a protein involved in the uptake of viruses might affect other biochemical processes and create new vulnerabilities, such as an increased susceptibility to other infectious diseases.

“Gene editing is very precise, but it's not 100 percent precise. There could be some mutations that could create problems for the children in the future,” he said.

Gene therapy has a three-decade history of trials and is the subject of regulatory protocols understood worldwide. This is not the case with germline gene editing, notes Professor Richard Ashcroft, a deputy editor of the journal Medical Ethics and a professor of bioethics at Queen Mary University of London.

An adult or older child treated with gene therapy is able to give their approval for the technique to be used, and because the science is more mature, has a better understanding of the risks. An embryo altered by genome editing cannot, of course, consent, and the risks are more uncertain.

_________________

More from science:

NYUAD research could help safeguard climate change-damaged corals from disease

Jobs for the boys? New study shows how career paths can be guided by gender

How plastic is getting into our food and what it means for us

_________________

“The embryo that has been created will bear the risk, but won't have any knowledge of what the risk is. We may not have any idea of what the risk is,” said Prof Ashcroft.

Recent history suggests there is no guarantee that a technology will be adopted simply because it has been invented; scientific and political opposition may remain insurmountable.

Prof Jensen cites the fact that the human cloning has not happened, despite the first cloning of a farm animal from an adult cell having taken place more than two decades ago.

“There could be something similar here. If the scientific community agrees more or less this is a step we should not take, it could be that the politicians decide there's something here. I hope there will be legislation saying this should not be carried out,” he said.

One suggestion is to restrict the use of the technique to cases where it offers a unique benefit. Among those sympathetic to this view is Professor Pascal Borry, co-author of the book The Human Recipe: Understanding your genes in today's society and a professor of bioethics at the University of Leuven in Belgium.

“If we really want to use it, the added value should be clear in the sense it should be enabling something we cannot do through other procedures,” he said.

So, he suggests, there might be situations where it is allowed if is the only option for dealing with a particular condition – such as when pre-implantation genetic diagnosis is not a solution – and if it is completely safe.

Using technology to create designer babies would be 'step too far"

“I don't say no from a principle basis but there should be no other alternatives available,” he said.

“Where it's not acceptable would be to use it to enhance certain traits. That's a step too far.”

An era of “designer babies”, then, in which parents select particular characteristics that they would like to see in their offspring, is likely a long way off.