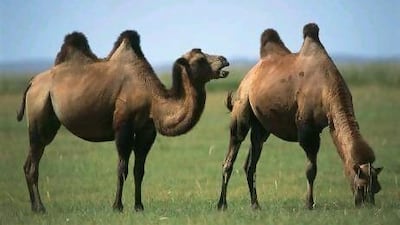

DUBAI // Fifteen rare Bactrian camels have been bred in Iran, thanks to technology from a Dubai centre.

"Bactrian camels are under threat of extinction in Iran," said Amir Niasari-Naslaji a professor of veterinary medicine at the University of Tehran, which four years ago formed a partnership with the Camel Reproduction Centre in Dubai to save the endangered breed.

"We only have 156 of them left here, so this project is crucial to conserve their species."

For centuries, Bactrian camels were used for carrying food by nomad tribes north-west of Iran, in the province of Ardabil. But once vehicles were introduced the tribes stopped taking care of the animals, which led to their near-extinction.

"The number of animals decreased drastically after that," Prof Niasari-Naslaji said.

He began transferring embryos of Bactrian camels into others, but with so few of them and a gestation period that lasts 13 months, results were not as good as hoped.

"We would only get one calf every two years and a half," Prof Niasari-Naslaji said. "So during the natural life span of the camel, we could only get four to five calves in very optimal conditions."

To increase that number, Dr Lulu Skidmore, a scientific director at the centre, cross-bred the Bactrian camels with dromedaries to increase their birth rate.

Bactrian camels act as donors and dromedaries as surrogate mothers.

"Instead of breeding one by one where you get two calves every three years at best, so a herd of 30, you've got an extra 20 to 30 within six months," she said. "That's another useful way of trying to conserve species by cross-transferring embryos."

And according to Prof Niasari-Naslaji, that could bring several eggs a year from one female so a total of 50 calves during the same life span of the female.

There are about 150,000 dromedaries in Iran, so although their gestation period is also 13 months, they can still manage to increase the birth rate.

Another approach used by Prof Niasari-Naslaji was to freeze the Bactrian camel's semen. He now has 4,000 doses.

Not only is he able to produce more calves, but the animals now also come out stronger and with more meat on their bones.

"They turn out bigger, they grow faster - about 200 to 300 more grams a day compared to the pure breed of Bactrian camels, and they have more meat," he said. And that will increase meat production in Iran.

Another benefit of the new breed is its resistance to hot desert weather. In Iran, Bactrian camels are found up north, and they can only handle cold weather down to -20°C.

"But they cannot tolerate the hot environment," Prof Niasari-Naslaji said. "When transferred to a hot climate, they die after two years. In Mongolia and China, they claim their Bactrian camels can sustain weather conditions between -40°C and 40°C."

Therefore, he is also working on another project to help the camels better adjust to weather changes.

"If we place the dromedary in the desert after transferring an embryo from a Bactrian camel, then it will be able to handle the heat and pass this on to its calf," he said. "This hasn't been done anywhere else in the world yet."

So far, five Bactrian camels have been able to handle the desert heat in Iran, and the country's agriculture ministry plans to convert more to be able to survive in 50°C heat to increase the population of Bactrian camels.

"This will help people who have Bactrian camels in other areas of Iran as they can breed them anywhere it's hot, not just in the north," he said.

He also believes that investing in the species will benefit humans in the future.

"They are important for our well-being," he said. "If you have a flock of Bactrian camels with dromedaries, you can enhance meat production, which is a good economical aspect. We don't know as of yet scientifically how they can help, but if we don't conserve them, we will never be able to find out."