His head pounding from the searing tropical heat, every limb aching from the back-breaking task before him, Eider Rua sighed as he bent double once again to dip his paintbrush into a pot.

As he straightened up, wiping the sweat from his brow and wincing from the pain in his knotted neck, he paused, loaded paintbrush in hand, and glanced across the road for what seemed the thousandth time that day.

He could only gaze in envy as swarms of smartly dressed schoolchildren began traipsing into the Ignacio Vasquez dance school, their laughter and excited chatter filling the air.

As the lights flickered on in the school, strains of Latin music filtered out onto the street, interrupted only by the odd shouted instruction and the clatter of shoes on wooden floors as the pupils were led haltingly through their steps.

Eider could only dream of joining them. Pulled out of school at the age of 12 when he failed his grades, thanks to the distraction of his first romance, he was sent to work by his father, Emilio, to help pay the family's bills.

Born in a deprived neighbourhood in Medellin, Colombia, where about half the population still live below the poverty line, Eider experienced a life in the Rua household that was fraught with hardship. The teenager still remembered the time five years earlier when his father had been out of work for a year and the family was forced to live hand to mouth in a makeshift home in the mountains, a shack divided into two rooms by a curtain hanging down the middle.

Now that he had found regular work as a taxi driver, Mr Rua earned enough to put food on the table by working seven days a week from 5pm until 5am, but luxuries were unheard of.

As well as struggles at home, the streets were riddled with danger. Medellin was the stamping ground of one of the world's most infamous drug barons, Pablo Escobar, whose drug cartel controlled 80 per cent of the global cocaine market.

Mr Rua feared that like many teenagers, Eider would become embroiled in drug abuse, gang warfare or the violence that plagued the city. So he put his son to work, toiling eight hours a day painting billboards for a signing company for US$50 (Dh180) per month.

"My family was very poor and my father said I could not continue my studies because the uniform and books cost too much money," says Eider, now 31 and living in Dubai.

"So I started painting. It was hard work but I learned very quickly. There was this dance school across the road from my workplace and every day I would stare at it, wanting a lesson - but I did not have enough money because I had to give my father half my salary for rent and food."

In the 1980s, the drug-fuelled economy saw an explosion in salsa and live music clubs as cartel ringleaders embraced decadent lifestyles.

Colombians became renowned worldwide for their brand of salsa, involving much faster, more energetic footwork than the Cubans and Puerto Ricans who gave birth to the dance.

Cali in Colombia was dubbed the salsa capital of the world and still boasts 200 dance schools, while Colombians have won the World Salsa Championships for the past five years.

Keen to learn to dance to the infectious beat, 12-year-old Eider approached the school owner, Mr Vasquez, with a gem of an idea: "He had very bad advertising so I said I would do a deal. I would paint something for him and he would give me classes in return."

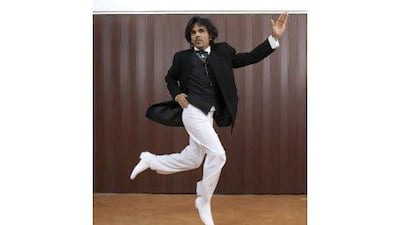

It was an ingenious plan that was to change the course of his life. Nearly two decades on, Eider - whose incredible life story reads like the script of a classic dance movie - is now a world-class salsa champion with dance schools in Colombia, Dubai and Abu Dhabi.

He has ambitions to franchise his winning formula to Tokyo, Madrid, London, New York and China, as well as to open a community centre in his home city, where youngsters on the street would be given free

dance lessons to take them out of poverty and away from the dangers of drugs.

Next week he will compete alongside his dance partner, Luisa Suaza, 21, in the World Salsa Championships in San Diego in the US. He hopes to bring home the trophy, topping their second-place finish from last year.

Those initial lessons in porro, a folkloric dance from the Caribbean region of Colombia, were exchanged for painting figures dancing across the walls and windows of Vasquez's school. They put Eider on the path to becoming a star and reversing his family's fortunes.

However, had his traditionalist father got his way, Eider would never have set foot in a dance school.

"I wanted to learn porro because people danced it at all the parties. My father thought dancing was for girls and told me I had to stop," says Eider, sitting in his office in Dubai's Knowledge Village surrounded by medals. A slight, smartly dressed figure with shoulder-length hair, he speaks haltingly but passionately of his love of dancing in a strong Colombian accent, repeatedly stopping to check his terms of expression.

"He had driven a taxi all his life and did not think dancing was fitting work for a man," he says of his father. "I argued with him and said he already took half my salary and pointed out that I did not have to pay for lessons, but he would not budge."

Like his cousins who had become addicted to drugs, Eider was hooked on a different addiction - dancing - and soon carried off the top prize in a Medellin porro competition.

"At that moment, I decided I wanted to dance every single day," he says. "My teachers told me to come to a place at night to see them dancing the tango but because my father did not want me to continue, I had to climb out of the window of my first-floor bedroom and sneak out. I carried on having dance lessons in secret for six months and started to meet other dancers, who wanted to help me because they said I was good.

"The lessons cost $4 (Dh14) a week so I would do anything in my spare time - fix car radios, teach people to dance on street corners or in their homes for $1 - just to make enough money to pay for them without my father finding out."

His furtiveness did not go unnoticed. Twice, family friends tipped off his father and Eider was dragged out of the dance school by his hair and ordered never to return.

The bitter family rows finally reached a climax when, in a fit of pique, the teenager told a child protection officer about his father's strict behaviour and she threatened to investigate the family circumstances.

"My father was very upset and so angry," Eider recalls. "He said he would lock me in a room until I got down on my knees and said sorry - or I would never leave the room again. I was very strong because I had not done anything wrong and for 15 days, I stayed in that one room. Finally I thought: 'I will apologise but I am not really sorry'."

Secretly, he was plotting his escape. Once he had made his peace with his father, he sold all his painting materials and his bike and, with $120 (Dh440) in his back pocket, crept out of the house under cover of darkness and boarded a 5.30am bus to Bogota.

A runaway at 13, he suddenly had to fend for himself on the streets, wondering if he had made a terrible mistake. "I thought, what am I doing? I don't know anyone and have never been anywhere other than home. I cried for most of the journey."

Ten days later, he was back at the Bogota bus station, having failed to find work, penniless and morosely contemplating his father's wrath when he returned. As he was preparing to board, he made one last phone call to thank a kindly dance instructor who had put him up.

"He had just watched the video I gave him of the porro competition I won and said: 'Don't leave, I want to work with you.' It was the best moment of my life. For me, this was the moment I became a dancer."

But as happens in all good dance films, he first had to transform himself: "My boss's school was in a very good part of Bogota but I came from a bad area and had bad hair. He told me I danced well but had to cut my hair and change my clothes."

Eider taught well-to-do students in their homes for $10 a class and began to dream of providing for his family: "I never knew people could live like that - I could feel the money. It was another life and I started to think: 'I want this for me and my family'."

Eighteen months later, he returned to Medellin with $300 (Dh1,100) in savings and presents for the family. "I felt like a millionaire," he says.

At 14, with his earnings matching those of his father, he was convinced he would finally be independent.

But while Mr Rua had come to begrudgingly accept his son's choice of profession, he had other ideas about discipline: "He said, 'If you want to live under my roof, it is on my conditions'. I never smoked, drank or took drugs like my cousins so did not understand why he was telling me what to do."

Eider left home again at 16, unable to get along with his father. However, he stayed in Medellin and got a job at the prestigious La Magia de Tus Bailes dance school. He began writing down his dreams and posting them on his bedroom wall. "I wanted to compete internationally and be part of a famous dancing couple," he remembers.

"I felt it was good to write down what you want and have a five-year plan, even at a young age."

He failed to pass the audition for a Colombian national tango troupe so, undeterred, he decided to open his own dance school in Medellin in 2000, the Ballet Nacional el Firulete (BNF). Its eight instructors taught everything from salsa and merengue to flamenco and samba, and also performed on stage and at weddings. Within a month of opening, they had carried off first prize in a national tango championship.

At the same time, Eider, then 22, was searching for his own dance partner to compete internationally. The sprightly, effervescent Suaza, who had learnt to dance at the age of six, shone out from his other pupils but he was at first hesitant to pair up with her because she was only 12.

Her skills, a perfect match for his, soon won him over. In December 2005, they were asked to perform in Dubai by a hotel group and were dazzled by the pace of development.

"In Medellin, we had no more than 10 hotels and that provided enough work. I thought, 'Imagine how much we could do with 200 hotels'," says Eider.

He arrived several months later with 14 dancers from Colombia to set up his first international base, in Knowledge Village. Business has been so successful, the troupe is often asked to perform at private functions around the world, from Egypt and India to Europe. BNF Dubai now has 250 students. The school, which has a turnover of more than Dh2 million a year, has just opened an Abu Dhabi branch in the One to One Hotel, and Eider hopes to expand to other countries.

On Tuesday, he and Suaza will be in San Diego to compete in the World Salsa Championships. Last year the couple came second in the cabaret division.

When he takes to the floor, Eider will think of the page in his diary, where he still writes down his dreams. They include wanting to carry off the top trophy in the contest, as well as getting married, having a family, buying a home in Dubai and opening a community hub to help other children with the same background he came from.

But top of the list, next to a photograph of his family, is ensuring his parents and siblings never have to work again. For, in a remarkable twist, three years ago his 55-year-old father joined his mother, Oliva Giraldo, 57, his three sisters and his brother in running Eider's dance school in Medellin.

"I told my father I did not want him to work as a taxi driver any more and would cover any salary he got," says Eider. "He is very proud of me now and we have a great relationship.

"I thank him for pushing me as much as he did. When I look at the Burj Khalifa, my new car and my BlackBerry, I still have to pinch myself as I remember a time when I had nothing. It is just proof that if you think it, you can make it happen."

Put on your dancing shoes

There are plenty of dance schools across the UAE where you can learn dances such as salsa (a fast-paced Latin American dance with a partner) and tango (originating in Argentina, where the couple closely mirror each other's movements). Here are six:

BNF Dubai - Block 14, Knowledge Village. 04 364 4881/050 3550180, elfiruletebnf.com, e-mail school@bnf.ae; Abu Dhabi - Villa 5, The Village, One To One Hotel. 02 495 2095/050 451 5127, adschool@bnf.ae

NORA DANCE GROUP Abu Dhabi - Intercontinental fitness club; Dubai - Marina Mall, Ductac in Mall of the Emirates and Knowledge Village. 050 395 8280, www.noradancegroup.com, or e-mail noradancegroup@gmail.com

ABU DHABI COUNTRY CLUB Abu Dhabi - Al Saada Street. Beginners' salsa class, Dh50, 8.30pm on Sundays, 02 657 7777

HILTONIA HEALTH CLUB Abu Dhabi - Corniche. Beginners' salsa on Sundays and Wednesdays at 8pm, Dh35, 02 692 4324, www.danceabudhabi.com

ARTHUR MURRAY DANCE STUDIOS Dubai - Reef Tower, Jumeirah Lakes Towers, 04 448 6458. www.arthurmurraydubai.com

RITMO DE HAVANA Dubai - Ductac. Cuban salsa course beginning January 15, 050 696 3520, www.ritmo-de-havana.com, or e-mail delpiero2000me@gmail.com