It was a fortuitous and completely unexpected discovery.

Last year, Liza Rogers was working in the archives of the National Maritime Museum in London looking for documents relating to the history of Qatar.

Ms Rogers thought that a leather-bound, mid-19th century sketchbook belonging to one R W Whish might contain just the kind of interesting material to bring her subject to life, with observations and details normally absent from official surveys, charts and reports.

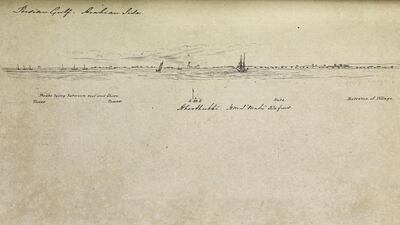

As she leafed through the book’s faded pages, something quite different captured her attention: a faint, 155-year-old pencil sketch depicting a horizon, sheltered by light cloud and defined by a fort, some towers and the masts of several ships.

The drawing had a subheading beneath it. In Whish’s fine copperplate script it said, “Aboothubbi, HMS Mahi, 3½ fms”.

Ms Rogers immediately realised the value of her accidental find and informed Eric Langham, her boss.

Whish’s sketch might be questionable as a work of art, but it is invaluable as a piece of historical evidence.

What Ms Rogers had uncovered was nothing less than the earliest known sketch of Abu Dhabi.

“A new image of Abu Dhabi from this period is gold dust,” Mr Langham explains.

“This is the first sketch image we have of what is now one of the most important cities in the world today.”

The co-founder of Barker Langham, a London cultural agency that specialises in research, design and planning of exhibitions and museums, Mr Langham is well qualified to make the assessment.

Barker Langham has been working in Abu Dhabi since 2005 and is responsible for the content and curation of the Wilfred Thesiger exhibition at Al Jahili fort in Al Ain, and the Qasr Al Hosn exhibition in Abu Dhabi.

“For a number of years our job was to find out as much as possible about Abu Dhabi and Qasr Al Hosn,” Mr Langham says.

“We thought that we had a pretty definitive record of the evolution of Abu Dhabi and we thought that there wasn’t much more out there.

“You have the 1822 trigonometrical survey and then you don’t have much, apart from some records of people who went there, until Samuel Zwemer’s [1901] photo and that was only of the fort.

“We don’t have a very good sense of how the city evolved at all.”

Excited by the discovery of the sketch and the information it contained, Mr Langham immediately emailed a copy to Mark Kyffin, head of architecture at the Tourism and Culture Authority Abu Dhabi.

Mr Langham knew that one detail in particular would set Mr Kyffin’s pulse racing – the inclusion of two previously unknown towers, carefully proportioned and clearly labelled on the horizon to the left of Qasr Al Hosn, in the direction of what is now Mina Zayed.

“When I first saw the sketch it was as a revelation, not least because it seemed to confirm a theory that I’d always had, that Abu Dhabi originally had more towers.”

Mr Kyffin says: “We all know the legend – there was a singular watchtower built to guard the island’s potable water supply, which eventually grew into Qasr Al Hosn; that Sheikh Shakhbut’s [then Ruler of Abu Dhabi] modern palace was wrapped around this inner castle, and that the modern city of Abu Dhabi developed around that.”

Ever since Mr Kyffin began developing a conservation management plan for Qasr Al Hosn in 2007, tantalising fragments of evidence started to emerge for towers other than those known to be at Qasr Al Hosn and the Maqta crossing.

A sketch map made in the 1930s by the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company geologist P T Cox, who visited Abu Dhabi twice between 1934 and 1935, also reported the presence of a tower where Saadiyat Island nears the mainland.

Unfortunately, no physical or photographic record of it has ever been found.

But supporting evidence has been found for a tower in the area now known as Al Bateen.

Testimonies from older Abu Dhabi residents mention a burj in the area and this is corroborated by the survey conducted between 1822 and 1826 by map makers from the East India Company’s navy.

On the section of map dedicated to “Abothubbee”, the area now known as Al Bateen is clearly marked with both a village and a tower.

A mysterious feature, dark, columnar and taller than a tree, also appears in several photographs of Al Bateen including one taken from the roof of Qasr Al Hosn by Prof John Wilkinson in the early 1960s, and a 1952 aerial photo of Al Bateen taken by Ronald Codrai. Neither are conclusive, however.

When Mr Kyffin received Whish’s sketch, he turned to the person best placed to scour the photographic archive for evidence of more towers.

Justin Codrai, son of Ronald and for many years the keeper of his father’s estate, works for Abu Dhabi’s National Archive.

“Having spoken to Mark, I started looking at aerial views that my father took of the Mina area,” Mr Codrai says.

“In theory, there ought to be somewhere around here so I started looking from different angles and there is something, on a view from 1959.”

While it is impossible to tell whether the structure in Codrai’s photographs is a burj, towers at key defensive points is something that chimes with conversations Justin Codrai had with his father.

“My dad told me that there used to be watchtowers in Dubai that ringed the town and that they were close enough for people to be able to shout to each other,” Mr Codrai says.

“One of the things that my dad used to do to amuse himself in the evenings – this was a time before television and radio – was to go outside and call to the guards, and he would then hear the response go all around the town.”

For Mr Langham and Mr Kyffin, the idea that Abu Dhabi also might have had towers at strategic points around the island sheds a half-light on a previously uncharted moment in the city’s urban development and lends nuance to our understanding of the city’s genesis.

A significant part of that explanation lies in Abu Dhabi’s geography.

“There are too many old oral histories to discount the theory that the Baniyas left the Liwa Oasis to come and settle Abu Dhabi Island because of that, but for me that settlement was also very strategic,” Mr Kyffin says.

“As an island, Abu Dhabi forms a natural topographical fort in the landscape.

“It has surrounding khors that go all the way around it, like a moat, and they are also very shallow, which effectively prevents any vessels from sailing too close.”

Mr Langham also believes that the sketch provides an opportunity for historians to set this moment in Abu Dhabi’s history in a broader social and political landscape.

“There’s the great story of the gazelle finding the water and the settlement and the fort,” he says. “It’s simple and it’s easy and it’s true in one respect.

“But there are levels of sophistication that sit alongside that story and this drawing shows some of that.

“We know that the mid-19th century was a very turbulent time for the Baniyas and this image shows that Abu Dhabi was larger and better protected than we may have considered. It also illustrates the political and strategic acumen of the Baniyas.

“This was a time when all of the major players were moving to the coast and establishing the towns that have now become the major cities of the Gulf.

“This sketch documents not just Abu Dhabi’s emergence as a pearling centre in the Gulf but as a player on the world stage.”

nleech@thenational.ae