It is a question that has long vexed researchers from this region: why did the Muslim world, which once led the way in science, fall behind?

The issue is as pertinent now as ever, with the Middle East still lagging behind the global average when it comes to spending on research and development and concerns continuing over a regional “brain drain”.

To look for answers, earlier this year a task force on "Culture of Science in the Muslim World" was set up, bringing together nearly a dozen Muslim scholars, several of them scientists, based in countries including the UAE, Pakistan, Malaysia, Lebanon and Australia.

The task force met to discuss its findings at the World Science Forum, held recently at the Dead Sea in Jordan.

A key area of interest is why the innovation of the Islamic Golden Age, which ran from about the eighth to the 13th centuries, was not carried through until later periods.

“I think the Golden Age started in the seventh century or the beginning of the eighth century and it was energised by our theologians taking the Greek philosophy, the rationalist philosophy as a means to work out quarrels they were having about the divine text, the Quran,” said Professor Jelel Ezzine, a professor of systems theory and control at the University of Tunis El Manar in Tunisia and one of the task force’s members.

“Baghdad was among the epicentres of these activities and the famous Bayt Al Hikma [House of Wisdom, a library] was the Mecca of scientific research and where all the scientists from all over the world and all faiths came to study and contribute to that enlightenment.”

Prof Ezzine feels that scientists are particularly suited to coming up with answers about what happened because they have “some understanding of science and the practice of science”. They can cast “a neutral look”.

“One has to have a reasonable methodology, be as objective as possible, leaving biases as far as possible, and limit ones analysis to key events that we call bifurcation points or events that might look at the time insignificant, but can really help to facilitate the emergence of large dynamics,” he said.

Such large dynamics could have had consequences that last until the present day. Globally, spending on research and development averaged 2.23 per cent of GDP in 2015, according to World Bank figures, but in most of the Middle East, it is far lower.

In the UAE, for example, the figure in 2015 was 0.87 per cent of GDP, while in Saudi Arabia, it was 0.82 per cent in 2013, the most recent year for which data is published. In Kuwait, 2013’s figure was just 0.30 per cent, while Oman recorded 0.25 per cent in 2015.

Many other Arab countries, especially those in turmoil because of conflict, have much lower R&D spending.

However, investments in R&D in the Arab world are increasing, with the UAE’s 2015 figure almost double that of four years earlier, while in Saudi Arabia there was a 10-fold increase in research and development spending between 2003 and 2013. Spending worldwide has increased much more modestly, from 1.97 per cent of GDP in 2015 to 2.23 per cent in 2015.

When it comes to understanding why the Muslim world fell behind at the end of the Islamic Golden Age, Prof Ezzine says that three factors should be considered. He describes them as “the rulers, the religious and the rationalists”, which equates to religion, politics and science. Understanding how those in power regarded science helps to explain trends.

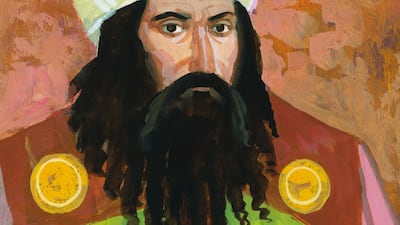

Among the key historical figures is Al Ghazali, a Persian philosopher born in the 11th century.

“He refused the existence of cause and effect outside the divine will,” said Prof Ezzine, who shares the view of many observers that Al Ghazali limited scientific progress in the Islamic world.

Although the Marrakesh-born 12th-century polymath Averroes forcefully took a different view in his writings, defending the philosophy of the likes of Aristotle against attacks by Al Ghazali, Prof Ezzine feels that the course had been set.

“It was extremely difficult to rebound from Al Ghazali’s spell,” he said.

It was, he says, “the interaction between the church, the scientists and the politicians” that enabled the West to pull ahead after a long period of trailing the Muslim world.

While researchers will continue to have different interpretations of why the Islamic world’s pre-eminence in science was lost, Prof Ezzine is clear that the achievements of the Islamic Golden Age are often inadequately recognised.

He cites Ibn Khaldun, an Arab intellectual born in Tunis in 1332 whose writings covered many subjects. Prof Ezzine says that much of what was written by Adam Smith, the Scottish author of the highly influential The Wealth of Nations, was influenced by Ibn Khaldun.

“The western world took a lot from that period,” he said. “He came at the end of the Golden Age, but he’s also a modern man. He came at the junction between the end of the Golden Age and the beginning of the modern age, so he’s a great witness to this metamorphosis, a must to read.”

Prof Ezzine says that new areas of science can offer insights into historical events and could encourage better outcomes in the modern world.

“It’s a very, very wide problem and there’s a need to do something much deeper … [to] analyse things in an objective scientific manner using the new sciences of psychocognition, complex dynamic systems and other new fields to [develop] more relevant conclusions,” said Prof Ezzine.

“The objective is to reignite the practice of science in the Muslim world for the benefit of Muslims and the rest of the world and for peace on Earth.”