When David Pryce arrived in the UAE in 1977, home was a cabin on a sand dune. He had no electricity or air conditioning and dinner was a chicken curry cooked over an old oil drum.

Mr Pryce, then 20, was leading a project to plant tens of thousands of trees around the village of Ghayathi that was being built in Abu Dhabi's Al Dhafra region.

The afforestation scheme was part of a huge project of tree planting initiated by the President, Sheikh Zayed, who was building permanent homes for the nomadic Bedouin in the parched desert.

Sheikh Zayed hoped the trees would provide shade, improve the appearance of the villages and make them more liveable.

It was also believed this green belt could cool the sun-punished area by a few degrees. And it was people like Mr Pryce who made it happen.

“It sounded like a good adventure,” he said. “But I didn’t know what I was getting myself in for.”

The UAE had only been formed a few years earlier. And people were pouring into the Emirates as oil revenue began to transform a country that needed new schools, hospitals and houses.

More than four decades on, Mr Pryce recalls these pioneering days as if they happened yesterday. He was no stranger to the Arabian Gulf, having served with the UK’s Royal Fleet Auxiliary when he was just 17, which was a supply chain for the Royal Navy.

But it was an association with a British landscaping firm that would change his life.

"From the age of about 11, I worked for Verge and Embankment Beautification during my school holidays cutting grass, weeding and stone picking," he said. "They called me up out of the blue to see if I wanted to plant a few trees."

Mr Pryce, an Englishman, arrived in July, 1977, and travelled to the camp 250 kilometres from Abu Dhabi a day after landing at the capital’s Bateen Airport. The heat was searing, the sand endless and the job tough. There was no fridge or water supply and a basic shop many kilometres away only stocked flour and rice. “Rainbow Milk in a tin was popular.”

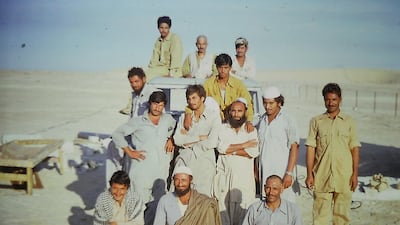

Mr Pryce, 63, led a team of about 30 Pakistani workers in planting more than 80,000 trees – many of them ghaf and cedar – around Ghayathi.

These new towns were being built on the traditional routes of the nomadic Bedouin to provide them with new homes. Ghayathi was nearing completion with a clinic and school when Mr Pryce arrived. People began moving in a few months later.

An article from trade magazine, Middle East Economic Digest, that year outlined the challenges facing these types of afforestation projects. It raised concerns over the long-term sustainability of the project chiefly because of the huge water use involved. Another issue was the scale. To alter the climate, millions of trees would be required.

“The forests sprouting in the UAE are intended to draw the Bedu to a less nomadic life and will change the country’s climate,” it said. “The optimism is not shared by the consultants.”

Mr Pryce admits that a staggering amount of trees would be needed to alter the climate.

“Trees have a cooling effect but you need a great many. When you walk among them you feel cool but outside this belt the [scale] is not big enough.”

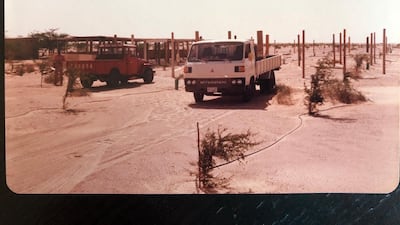

Another problem was trying to keep the camp supplied with fencing, concrete and other materials. This involved a long and painful drive every few weeks in a lorry without any air conditioning to Abu Dhabi's Mussaffah, which even then was a labyrinthine industrial area.

“There were no roads or accommodation and businesses there,” he says. “It was just sitting in the middle of the desert. And when it rained, it turned into a quagmire.”

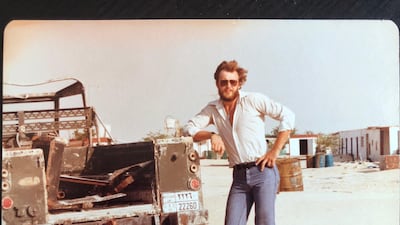

Mr Pryce's time in the Al Dhafra region was chronicled in a series of incredible photographs. One shows him in flared 1970s jeans, while another shows the Pakistani workers posing like a victorious football team. Others underline the epic scale of task.

One photograph in particular shows the young trees swaying against the vast and unrelenting desert.

Mr Pryce left the project after four years and it was handed over to Abu Dhabi Municipality. He stayed in the UAE and revisited the camp last year. A few pieces of concrete and twisted metal poke through the sand and the desert has reclaimed the rest of what had been his home.

“I stood on the hill of the camp and wondered: 'how did I live here for four years?’” Mr Pryce recalled. “It was hardship but, at 20, life is very different.

Important too to note was the increasing awareness by Abu Dhabi regarding the use of water. Authorities have shut off the water pumps to some of plantations and many of those that remain are of the hardy ghaf variety that have sunk roots down to the water table. Those that remain help prevent soil erosion.

Mr Pryce's story is like that of tens of thousands of people who moved here in the early days. It was a freewheeling time when these pioneers played a vital contribution in building the country up and trying new things to make the UAE what it is today.

“As with many other people, it has been rough at times but if I ever leave the UAE, I shall always be looking back at the good times we all enjoyed.”