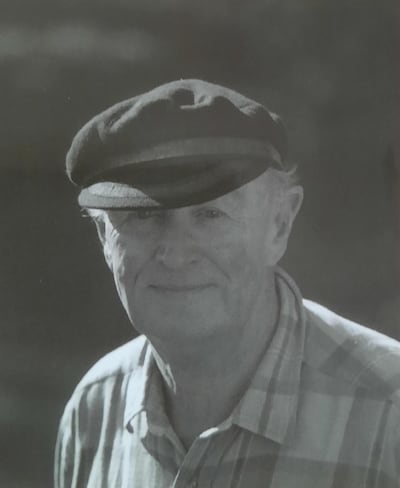

When Philip Horniblow arrived in Abu Dhabi in 1966, the task must have seemed immense.

As the first director of health, it was his job to build a network of hospitals from a blank slate.

His father went to school with TE Lawrence and some of the man’s spark kindled an interest in the region for the young Philip.

“The whole region was quite magical,” he once said of Arabia. But there was little romantic or magical about the task ahead.

Born in 1928 in the UK, Horniblow joined the Parachute Regiment after the Second World War before training as a doctor. But permanent life in the UK was not his fate.

This calling took him across the Middle East during the twilight of British presence in region. By 1966, he was in Abu Dhabi. The role could not have been more urgent. The first oil shipments left in 1962 and revenues were flooding in. But healthcare had yet to see substantive improvement.

There were no doctors, nurses or barely any trained staff. Child mortality was high, malaria and tuberculosis were rife, while even a small wound could lead to serious illness.

When Sheikh Zayed took over as Ruler of Abu Dhabi in 1966, up sprang hospitals, doctors were recruited and modern healthcare was introduced. Horniblow was part of this wave from 1966 to around 1970 as the first director of Abu Dhabi’s health service.

"One of his first challenges was to remove people with fake credentials and deal with what Horniblow described as 'colonial retreads'," Athol Yates, a professor at Khalifa University, who has written widely on this period, told The National.

“They had been colonialists in India before partition and Sudan. By the late 60s, some of these expatriates were set in their ways and were not suitable so he had to embark on a recruitment drive.”

But this brought a further set of challenges. Horniblow learned not to rely on written “references” and to doublecheck impressive-sounding qualifications. Another issue was ensuring people trusted the health service as there was an inclination to go abroad for expensive treatment.

He chronicled the immense task in his 2003 memoir, Oil, Sand and Politics and recounted how when Sheikh Zayed cut his foot on coral – which can have dangerous consequences – he deliberately sought out the local service to show confidence in it.

Horniblow, who brought the first X-ray machines to Abu Dhabi, also oversaw a study that found malaria could travel between Abu Dhabi and Dubai because mosquitoes could breed in dew that persisted in wheel rims. There were also failures.

Horniblow recounted the pattern of some to forge vaccination certificates to travel abroad and resist quarantine measures.

“His book is one of the best – he doesn’t glamourise the situation,” said Prof Yates.

“It links official history to the day-to-day challenges to the expatriates who ranged from honorable to misfits and everything in between. It is a real feeling of what it was like at the time. That is really unique.”

Horniblow was also the medical officer who flew with an Abu Dhabi Defence Forces humanitarian mission to Jordan in 1970 at the beginning of the conflict there. During his thirty-year spell in Middle East, he also served in Yemen and met the Bin Laden family of Saudi Arabia.

He was also a keen mountaineer and was a doctor on several expeditions to Everest.

By the time Horniblow was 50 he moved back to the UK. There he continued to work in the health services and also dabbled in painting until his death.