As diplomats and scientific experts debate the practicalities of the Paris climate change agreement at Cop23 in Germany next month, the UN can call upon one of its most important yet little-known creations for advice and support.

The UN University opened in Tokyo in 1975 and works as a scientific institute, where academics tackle global sustainability and environmental challenges.

Cop23 is this year’s iteration of the UN’s annual climate change conference, which takes place from November 6 to 17 in Bonn, where the focus will be on looking at ways to best implement the landmark agreement, the Paris Accord, struck by countries across the world two years earlier.

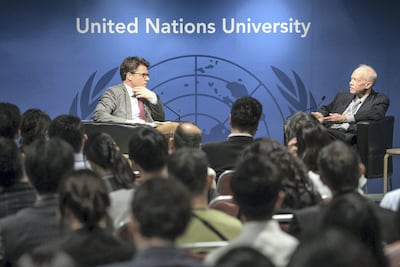

“While the Paris Accord deals with the issue of limiting emissions that contribute to climate change, there’s a great deal else that needs to be done on the environment in the developing world,” said Dr David Malone, the university’s rector.

The university is currently working on hundreds of research projects to find solutions related to all 17 of the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

Preparing for natural hazards is one of them, as climate change is strengthening an unprecedented number of natural hazards across the globe, such as tsunamis, floods, storms and droughts. As these occurrences continue to increase in frequency and intensity, the university says it is crucial to understand what influences them.

Each year, its researchers rank more than 170 countries based on their exposure and vulnerability to natural hazards. This index helps the international community better understand the drivers of disaster risk to minimise damage and shorten recovery time.

One of the university’s initiatives just won the UN Framework Convention of Climate Change’s momentum for change award for its efforts to bring key actors together to address climate risks and poverty by implementing climate risk insurance for vulnerable people in developing countries. The project enables individuals to sign up for climate risk insurance irrespective of their profession or income level.

Managing e-waste is another university initiative, with 47 million tonnes of toxic rubbish thrown out every year.

“That’s the same weight as the Pyramid of Giza, 10 Titanics, 30 Empire State Buildings and 50 Burj Kalifas combined, every single year,” Dr Malone said. “To help tackle this problem, UNU experts developed the e-waste world map, a website that displays the volumes, flows and environmental impacts of e-waste. This interactive resource provides clear and impartial data, helping governments and businesses identify major problem areas, better manage e-waste and keep our planet clean.”

At one of the university’s global campuses, in Dresden, Germany, a small group of researchers are working on recycling issues.

“They work on the basic idea that if you integrate water, solar and waste, what can be seen as problems separately can become resources when managed together,” Dr Malone said.

_______________________

Read more:

195 nations approve Paris accord to stop global warming to cheers and tears

UAE ‘meeting climate change demands of COP21’

End of the world as we know it is just ahead

_______________________

“If you recycle wastewater, you are going to be able to resolve part of your water supply and quality problems.”

Tackling such problems is at the core of the university, which has about 600 professionals and 350 students across its campuses and is far from being a traditional academic institute.

“It’s not programmes in political science or physics, it’s always something specific to challenges in the developing world and where perhaps some research work could be useful,” Dr Malone said. “The UN system has other research institutions, focused on specific issues like social policy in Geneva, but it’s just on one issue.

"Many of the issues we work on, there are scientists in other universities also working on, so our researchers are constantly partnering with scientists and other types of researchers in much bigger universities in the world.

“But what is unique about us is we’re inside the UN, so we can make available knowledge in forms to the UN system that may be easier for UN colleagues to deal with than your average research report or scientific journal, which policy-makers often find quite difficult to absorb and digest.”

The university’s other locations work on a variety of different topics, such as global health in Kuala Lumpur; natural resource management in Ghana; biotechnology in Venezuela; and globalisation, culture and mobility in Barcelona.

In his early years, Dr Malone lived in the Middle East in the mid-1960s, at a time when he said the Gulf had very little in terms of higher education.

“What’s interesting about the Gulf is that, today, higher education is a growth sector and many new, very good and strong universities have been opening up,” he said.

“This is very promising, the Gulf refashioning itself successfully as a knowledge and learning hub and that’s very interesting when you consider 50 years ago, there was nothing of that such going on.”

He said the Gulf today was very different to what it was in the Sixties.

“My father was in the diplomatic business at the time and was also accredited to Kuwait so we travelled up and down the Arabian coast of the Gulf and to Iraq and Afghanistan,” he added.

“It was a fascinating childhood. I have vivid memories of the Gulf and it’s done an extraordinary job in reinventing itself in the last 50 years.”

Itaru Yasui, a vice-rector at the university for four years and now president of the University of Tokyo, said UNU is more important now than it has ever been.

“University is very important for education globally and now the most important part of the UN University’s function is that this era is very quickly changing, so it has to provide points of view for people as to the goal of human activities in technology and science,” he said.

The birth of an institution

The United Nations University’s existence stemmed from a debate at the General Assembly of the UN during the 1960s, when its creation was backed by the secretary general at the time, U Thant, from Burma.

“He felt the UN was not particularly good at acquiring knowledge and using knowledge in its decision-making,” said Dr David Malone, the university’s rector. “So several institutions resulted from this long debate in the assembly and one of them was the university, which was established by a resolution of the assembly in 1972.”

The university opened in Tokyo in 1975 with remits such as developing knowledge on world hunger, natural resources and human and social development.

“One was the idea that the university would be oriented primarily towards the challenges and needs of the developing world,” Dr Malone said. “That was a point of departure. Secondly, while we were headquartered in Japan and for our first 10 years we worked exclusively out of Japan, subsequently we spread to other locations.”

The university’s building, which was handed over on June 30, 1992, was designed by the well-known Japanese architect Dr Kenzo Tange.

Famous for his merging of traditional Japanese architecture and modernism, he won the 1987 Pritzker Prize for architecture.

Dr Tange, a graduate in urbanism, also won a competition for the design of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park and has designed buildings across all continents.

Beyond being an institution, the university has always been a community of scholars studying and learning together, and an international community of researchers working in conjunction with UN diplomats to tackle many of the world’s most critical issues.

Though its administrative headquarters are in Japan, the UNU Charter always anticipated that the university would become “a worldwide system of research and training centres” operating around the globe.

Today, that goal is a reality as it is now a global network of 15 institutes and programmes carrying out dozens of applied research projects of direct relevance to the UN’s work, including global health, natural resource management, peace and governance and the environment, climate and energy.