Last weekend, I had the pleasure of meeting Prof John Mathew, an Indian academic on his first-ever visit to the UAE. His particular field of interest, on which he has written an excellent thesis, is on the evolution of the study of natural history in India, from the Mughal emperors to the end of the British Raj.

During that study, he identified several people in the late 19th and early 20th centuries -- military officers, civil servants and others -- who, for various reasons, also visited the Arabian Gulf, including the Trucial States, as the UAE was then known, making important early contributions to knowledge of the region’s history and natural history. Most were British by nationality – though many spent virtually all their lives in India – although among them was the renowned Surgeon Major A S G Jayakar of the Indian medical service, who spent many years as agency surgeon at the British Consulate General in Muscat. An avid collector of animals, he is remembered today by the Jayakar’s Oman Lizard, Omanosaura jayakari, also found in the UAE, and the endangered Arabian Tahr, Arabitragus jayakari, first described by a specimen he obtained towards the end of the 19th century from Jebel Hafeet.

The results of the work by Jayakar and others were not, of course, published locally, while the specimens they collected were destined for institutions in India or in London. The same pattern of local study, but foreign publication and storage, continued for most of the 20th century. Important information about the history of our natural history – how the studies of it evolved and the species new to science that were described as a result – is not available in the UAE, even if, thanks to the internet, an increasing amount can now, laboriously, be tracked down on-line.

The same is true, of course, of early documentation related to the history of the UAE and the rest of the Gulf and South-Eastern Arabia, much of which is held in the historical archives in Mumbai, London and Lisbon, in particular, but also in places like the Vatican and Venice. Work by the National Archives in Abu Dhabi is slowly amassing copies of much of that data, while an important project at the British Library in London is making much of previously inaccessible material on UAE history available for free download online.

Thus far, however, little has been done in terms of identifying the collections of fauna, flora and geological specimens deposited by avid amateur enthusiasts – and professionals – in foreign scientific institutions. Nor, as far as I know, has much effort been made to identify and to obtain copies of old papers about the country’s natural history and environment, many of which appeared in journals that are now defunct and near-forgotten. Little is known about many of those whose names still survive in the names of our plants and animals, like Blanford’s Fox or Sykes’s Warbler.

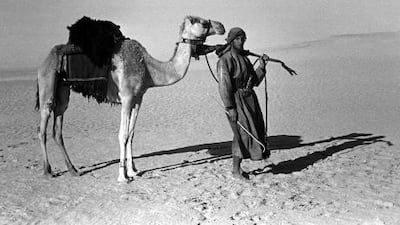

Yet much of the relevant information is available, if only there was the necessary determination to obtain it. From a preliminary investigation years ago of collections held at the Natural History Museum in London, for example, I was able to confirm that it holds literally thousands of specimens related to UAE flora, fauna and geology as well as at least summary details of those who collected them. Among them are specimens collected by the traveller Sir Wilfred Thesiger in the late 1940s – never studied – as well as copies of his notebooks. Here, though, we have no records of them.

There are, of course, many competing demands on Government budgets, while, though the UAE has a justified good reputation for its philanthropic initiatives in the spheres of humanitarian aid and disease prevention, it has yet to develop the types of internationally-credible research institutions dealing with our environment. Is it, perhaps, time for some serious attention to be paid to the collection, recording and analysis, as well as publication, of this important part of our history?