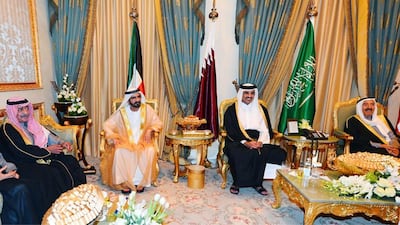

The diplomatic crisis between Qatar, on one side, and Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain and Egypt, on the other, will not sound the death knell for the Gulf Co-operation Council. To think of the GCC as a thing of the past would be an emotional and short-sighted reaction with irremediable consequences for the region.

Instead, the Qatar crisis represents a test of resilience for the organisation, and could, in the long term, give the GCC an opportunity to reinvent itself and better adapt to the challenges of our time.

As the Qatari crisis continues, rumours persist that the GCC union could break apart. Given the magnitude of the crisis, many observers believe the GCC has reached a point of no return. The wounds appear too deep to overcome the level of distrust, and time might not be enough to erase the negativity of the unprecedented media campaigns raging between the two fronts. This could lead GCC countries to reconsider current and future integration projects, such as the regional electricity and gas grid, the intra-GCC railway project, the introduction of a common value-added tax, or even prospects for a unified military command and naval force.

The GCC has been here before. Since its creation in May 1981, every time the GCC faced political crisis, the threat of disintegration emerged. In March 2014, Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Bahrain recalled their ambassadors to Qatar, accusing Doha of threatening the principle of Gulf unity for the benefit of Iran. But the Riyadh agreement, signed the same year, saved the GCC from breakup at the time. Today, the crisis is much deeper and far wider, but similar threats loom large in the horizon. While such a breakup might seem like the only remaining option, it is certainly not the most strategic one.

The dismantling of the GCC would create a bevy of problems. It would spur political and economic uncertainty in an already vulnerable region. Moreover, without an intergovernmental regional organisation to represent them on the international scene, Gulf countries would find themselves unable to contain the influence of Iran, India and even China, which would seek to fill the power vacuum. There is simply too much to lose in letting the GCC disintegrate.

This is why Gulf countries should embrace this crisis as an opportunity for reinvention. More than a crisis, the current impasse could spark a new beginning and demonstrate the group’s resilience. The GCC has been in need of reform for decades, and should jump at the opportunity to rethink its mission. The bloc was created in a different time, when Iran was expected to expand beyond its borders, when the US was militarily engaged in the region against a resurgent former Soviet Union, and when traditional and conventional war was still the norm.

Today, the GCC must rewrite its mission statement and find a new raison d’être, focusing on the main challenges of our times, such as climate change and the need for economic diversification. The GCC should prioritise human capital and implement a regional intergovernmental strategy to invest heavily in education and R&D, while proceeding carefully with institutional reforms to favour innovation. By putting aside political rivalries and focusing on win-win objectives, the GCC has everything to gain from its transformation.

There is a lesson to be learnt from the Association of South-East Asian Nations, or Asean, which was created in 1967 during the Cold War. The organisation underwent a significant shift in its modus operandi after the collapse of communism around the world. In order to remain an influential actor in the global economic arena, Asean filled the resultant political vacuum, realigned its mission to better cope with its new reality, and focused on the economic development of its five founding members (Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand). Asean managed to weather the storm to become a major global hub for manufacturing and trade, and one of the fastest-growing consumer markets in the world.

It is now up to the GCC to walk a similar path and show the international community both its strength and resilience.

Mylene Tisserant is a senior analyst at The Delma Institute, a risk advisory firm located in Abu Dhabi.