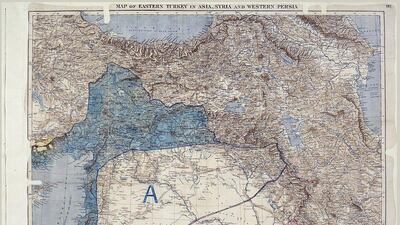

The centenary of the Sykes-Picot agreement has launched many reassessments of what might have been in the Middle East had Britain and France not agreed in 1916 to carve up the Ottoman Empire for their own purposes.

However, one thing it has not done is lead to a re-examination of the Arab nationalist interpretation of the agreement. The classical account in that regard is a book written in 1938 by the Lebanese publicist George Antonius, titled The Arab Awakening.

Antonius portrayed the Allied understandings over the Ottoman Empire as a betrayal of what had been promised to the Arabs, above all the Hashemite Sharif of Mecca, Hussein bin Ali. Britain had urged the sharif to revolt against the Ottomans, and made him believe that in exchange for this it would recognise a vast Arab kingdom under his rule.

However, while Britain was making promises to Sharif Hussein, it was also dealing underhandedly with France. Therefore, Antonius argues, the European powers thwarted Arab aspirations to build a state independent of both the Ottomans and Europe, instead imposing artificial borders to divide the Arab peoples.

It’s difficult to deny British double-dealing with respect to Sharif Hussein. But it would be naive to view this as undermining the Arab desire for an independent Arab state. What the British did was impede the dynastic ambitions of the Sharif of Mecca, which can hardly be equated with an Arab striving for unity.

In fact, it was the British who ultimately gave two of the sharif’s sons, Faisal and Abdullah, kingdoms that would be closely tied to Britain, guaranteeing Hashemite rule in Iraq and Transjordan after 1921. Far from being embittered Arab nationalists, the pair would emerge as pillars of British power in the Arab world, only five years after the Sykes-Picot agreement.

Nor is it clear that the Hashemites truly reflected an Arab consensus, so that equating them with broader Arab aspirations may be inaccurate. Faisal would definitely emerge as a leading opponent of France in 1920, before his Arab forces were defeated in the Battle of Maysaloun by a French army under the command of Gen Henri Gouraud.

However, to the elite of Damascus, which had thrived under the Ottomans, when they began favouring greater decentralisation in the context of the empire, there was uncertainty about a new leader arriving from the desert. These urban notables, who had played a significant role in devising the principles of Arab nationalism, were not sure that Faisal embodied them.

This urban-rural fault line was not the only one that places the notion of Arab unity in some sort of perspective. Uncertainty was also visible in Iraq, when Faisal took power. The Shia, among others, were initially hesitant about embracing this Sunni Hashemite king imported by the British. But Arab nationalism never played up the reality of sectarian divisions.

And such doubts were infinitely more pronounced among non-Muslim religious minorities elsewhere – above all the Maronites of Lebanon, who welcomed the French and did much to lobby for an independent greater Lebanon.

In September 1920 Gen Gouraud established a Lebanese state, to the displeasure of Arab nationalists. However, gradually they came around to accepting the new state and participating in its institutions.

To deny the power of Arab nationalism would be to falsify history. However, it’s perhaps also truer to say that the vigour of Arab nationalism expanded mainly in opposition to the European colonial powers during the interwar years, than to consider it as a dormant giant that the European powers only frustrated.

The Arab nationalist canon, almost by definition, cannot look at the many exceptions qualifying it. If an all-embracing Arab ideal exists, no room can be made for anything that separates the Arabs – such as religion, sect, tribalism or regionalism. To accuse the British and the French of dividing the Arabs implies the Arabs were united in the first place, when the picture was different.

Several years ago I visited Damascus. While there I realised how reluctant people were to discuss sectarianism. “That has more to do with Lebanon,” was the frequent reaction of people I met. Today, the country is being torn apart by sectarianism, while Lebanon, which acknowledged its sectarian system, remained united despite its war, largely because it had mechanisms in place to address the reality of its disunited communities.

Much the same holds for Arab nationalism. Though it was long held up as the secular religion of the Middle East, movement towards a single Arab state never made much progress during the postcolonial period. The borders of Sykes-Picot remained in place, heartily defended by regimes whose ideological foundations rested on a denunciation of western imperialism.

The centenary of Sykes-Picot should spur Arab nationalists to cast a light upon themselves. Blaming Britain and France is not sufficient for explaining the failure of Arab nationalism in the century since the agreement, let alone that of the modern Arab state. But myth is always easier to accept than the truth.

Michael Young is a writer and editor in Beirut

On Twitter: @BeirutCalling