The sixth Fatimid caliph, Al Hakim bi-Amr Allah, was famed for his erratic edicts. The caliph, who ruled much of North Africa and parts of Arabia between 996 to 1021, banned molokhia, watercress, as well as fishing and eating scaleless fish. He also forbade women from leaving their homes and outlawed shoemakers from making women’s footwear. One of his most bloody edicts ordered the extermination of Egypt’s canine population. Historians estimate that more than 30,000 dogs were killed and dumped in the desert and along the banks of the Nile. Such behaviour led historians to question Al-Hakim’s sanity. Adjectives such as psychotic, neurasthenic and megalomaniacal have been frequently used to describe the caliph in articles bearing titles such as The Crazed Caliph.

Because of the subjective and consensual nature of declaring a mental state as disordered, the powerful can often evade diagnoses and custodial care. A mad man for one person is a meal ticket or messiah for another. If your typically straight-laced boss walked barefooted into the office with flowers in his hair, declaring 100 per cent pay rises across the board, would you be immediately concerned for his mental health or would you just let things play out and hope for the best?

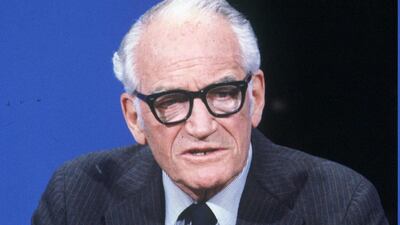

In a survey undertaken in 1964, more than 1,000 psychiatrists declared that the presidential nominee Barry Goldwater was “psychologically unfit to be president”. Goldwater later won a defamation suit against the magazine that published the results of the survey. In 1974, the American Psychiatric Association adopted the Goldwater rule, discouraging its members from “making public statements about public figures whom they have not formally evaluated”. Numerous distinguished psychiatrists question the ethics of the APA ruling, especially since public figures tend to be relatively powerful, thereby potentially magnifying the societal consequences of their delusional, irrational or impulsive behaviour.

Beyond public figures, odd behaviour among the rich and the powerful is often affectionately, or fearfully, dismissed as eccentricity. Meanwhile, the same behaviour among the relatively powerless or impoverished might be labelled psychosis (a severely disturbed mental state). Declaring a domestic worker “mad” is much easier than calling into question the sanity of the chief executive of a company.

Even once people are assessed for mental-health problems, psychiatric diagnoses appear to differ by socioeconomic status. For example, some argue that diagnostic bias makes it more likely for psychotic patients from higher socioeconomic backgrounds to receive the diagnosis of bipolar disorder rather than schizophrenia that is typically viewed as being more severe, debilitating and stigmatised.

_______________

Read more:

Dubai support groups helping tackle stigma of mental health problems

Panic attack, acute anxiety disorder - the results are debilitating and frightening

_______________

If the rich and the powerful can go under-diagnosed, then the opposite is also true, with the less powerful sometimes becoming victims of overzealous over diagnosis and even malicious incarceration. The Victorian era is infamous for cases where perfectly healthy individuals were confined to “lunatic asylums” on the nod of the “mad doctor”, typically at the request of scheming relatives. Classic cases included having elderly family members certified insane, thereby expediting access to inheritance and estates. Another common one was having a troublesome wife locked away pending a divorce. Several such cases of malicious incarceration are meticulously documented in historian Sarah Wise’s aptly titled book, Inconvenient people.

There are, of course, times when a person’s state of mind poses a danger either to self or others. In such cases, intervention is required. Our mental-health laws and the ethical codes of conduct issued by our professional bodies should help ensure that the most vulnerable remain well protected in such instances. They should also ensure that the least vulnerable, that is, the most powerful, are not conveniently neglected either.

Mental health acts and codes of ethical practice change and evolve to keep pace with social shifts. On July 6, the American Psychoanalytic Association publicly challenged the American Psychiatric Association over the Goldwater decision, informing its 3,500 members that it does not follow this rule. This controversial decision is essentially a green light for mental-health professionals to comment, responsibly and in the public interest, on the psychological states of public figures.

If physicians in the time of Al-Hakim would have voiced doubts about his sanity, I wonder what the outcome might have been.

_______________

Also read:

Masculinity under siege: why some men are more likely to turn to suicide than women

_______________