In the shadow of breaking news, the issue, and sometimes controversy, of cultural heritage remains.

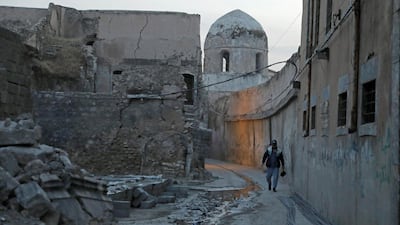

Last week, The National published an article about Unesco launching a competition to rebuild Mosul’s Al Nouri mosque, which was destroyed by ISIS in 2017. A global competition, notwithstanding its Iraqi subject, reminds us of our common responsibility to preserve heritage.

It also represents Iraq wresting back control from extremists of that which it rightfully owns.

At home and abroad, Iraq has recently scored a number of wins for its cultural heritage. This includes both the return of artefacts, in tandem with the development of local knowledge to protect, preserve and restore some of the world’s oldest and most precious treasures.

Examples of such successes include last month’s announcement by Britain to return 5,000 Iraqi artefacts by next year. It will be the largest repatriation of Iraqi antiquities in history.

This was not brought about by cantankerous politics, often a feature of debates around the ownership of cultural heritage. The transfer of these pieces is instead a vindication of a more collaborative and diplomatic approach.

And it is paying off. In another instance, the Iraq Museum in Baghdad and the Slemani Museum in Kurdistan, with help from the UK Cultural Protection Fund and other international backers, have recorded and marked with SmartWater – an anti-criminal tracking technology – 270,000 objects in just one year.

Across the world, institutions and centres of expertise are acknowledging this shifting approach to preserving our heritage, which focuses more on empowering local groups in home countries. This is correctly replacing the older preference for so-called rescuing of artefacts from their lands of origin. In emergencies this is justified, but it has throughout the ages become an excuse for hoarding.

One such programme that recognises this shift is the Nahrein Network. Based out of University College London and Oxford University, as well as ones in Kurdistan and Al Diwaniyah, the organisation aims to provide jobs for locals in the cultural heritage sector, tackling their historic exclusion.

Current progress in Iraq, therefore, makes a strong case for global cooperation in the fight for our history.

We also need to embrace rational debate when approaching the issue, as there will always be a fragile balance to strike between restoring our World Heritage Sites, powerful in their completeness of structures, artefacts, location and landscape, against the need to preserve global museums, where visitors can experience in one place objects from all over the globe, spanning pre-history to modernity.

We cannot do this by descending into nationalist political point scoring. The only basis of our discussion should be the wellbeing of our heritage. We owe it to our ancestors, who not only furnish our lives with beauty, but our very progress as a species. In the case of the Mesopotamia, now in present-day Iraq, this incudes breakthroughs in writing, farming, law and astronomy.

Access to a country’s heritage is an essential part of maintaining a common identity, particularly in nations recovering from violent trauma. It is no coincidence that groups such as ISIS, who wish only to impose their extreme and violent view of the world, revel in the destruction of that which will always outlast them: the beauty of our shared history and heritage.