When Covid-19 developed into a worldwide pandemic in 2020, perhaps the most frightening aspect of the mysterious new disease was that, at first, there was no vaccine and no treatment. Three years later, the recent re-emergence of the deadly Marburg virus in parts of Africa has rekindled similar fears and highlighted our vulnerability to sickness in a world that is more interconnected than ever.

Marburg, an Ebola-like virus that originated in fruit bats and can spread in humans through direct contact with the bodily fluids of infected people, has a death rate of 88 per cent. Although there are some treatments for specific symptoms that may help a patient survive an infection, there is no known cure.

The latest cases have been reported in Equatorial Guinea and Tanzania – countries that are on opposite ends of the African continent. Although, at 21, the total number of official infections is relatively low, there is no room for complacency, especially in a world where air travel has made it easier than ever for pathogens to move around the globe.

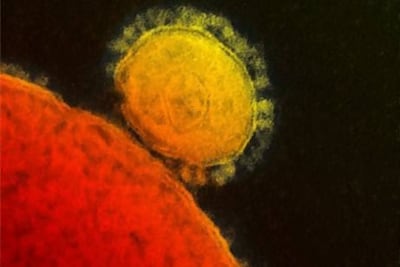

Some might claim that because treatments were eventually developed for Covid, we now live in a post-pandemic world. That feels reassuring, but it is not the case, and pathogenic threats remain. This week, researchers in Shanghai highlighted the "catastrophic" risks posed by a potential hybrid between the viruses that cause Covid and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, or Mers.

In this scenario, the high transmissibility of Sars-Cov-2 could be combined with the high death rate of Mers-Cov, which is about 100 times as deadly as the novel coronavirus.

And it is not just viral illnesses that are concerning. Research from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine published in this month’s edition of The Lancet Planetary Health found that the use of antibiotics in animals like cattle and chickens is associated with antimicrobial resistance in humans, a phenomenon described by the report’s lead author, Kasim Allel, as a “wicked problem”.

However, Marburg is not Covid-19 and over-reactions should be avoided – it is less transmissible than the coronavirus that swept the world in 2020 and the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention says it is still considered “a very rare disease in people” albeit one that “when it occurs, it has the potential to spread”.

It is a sense of prudence that has informed the decision by the UAE to join other regional countries, such as Saudi Arabia, in issuing an advisory for citizens and residents to postpone travel to Tanzania and Equatorial Guinea. The Emirates has also advised people travelling to the UAE from the two countries to isolate and visit a health centre for a check-up.

For the countries hit by the outbreak, no matter how limited it is, the economic consequences may prove to be grave. Tanzania is a popular tourist destination that is home to Mount Kilimanjaro and Lake Victoria. In 2019 more than 10 per cent of its gross domestic product came from tourism and last year it welcomed more than 1.4 million visitors. Many people there rely on tourism for their living and they will also be watching the latest travel developments closely.

Any assumption that rare diseases are problems for so-called developing countries alone is ill advised – very few places today can be considered “remote” any more. If Covid-19 taught us anything, it is that illnesses can spread – and change – at a speed that leaves scientists and healthcare professionals struggling to catch up. The world would do well to remain vigilant.