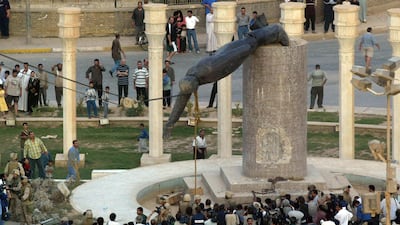

As the 2003 invasion of Iraq unfolded, I watched the statue of Saddam Hussein being toppled in Firdos Square on television at my family's home in London. It looked as if the entirety of the Baghdad population had taken to the street to topple the statue. My family and I wondered whether after 22 years in exile we would finally be able to go back to Iraq. What none of us watching realised at the time was that the images being transmitted were manipulated. The media had vastly exaggerated the numbers of those attending the toppling of the statue by using tight-focus shots. It was the ultimate fake news. What starts with a lie will end in disaster.

When Saddam assumed power in 1979, he began a crackdown on the communist opposition. As I have described in an autobiographical essay published in the anthology A Country of Refuge, my father Saad Abdulrazzak Hussain, an academic, was pressured to join the Baath Party. My family and I left the country soon after. During my childhood, I would often nurse daydream fantasies of storming Saddam's palace, assassinating the dictator and freeing my people. I had naively assumed that by removing Saddam, all of Iraq's problems would be magically solved.

My father, in his own way, had made the same naive assumption. Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, he was active in the Iraqi opposition in London. He would attend countless meetings, sign his name to various petitions and manifestos, give talks at this or that gathering. I viewed these activities with bemusement. I didn’t think he and his friends had any chance of affecting change in Iraq. But after 2003, things began to look different. My father was then working with Adnan Pachachi, a former foreign minister who ended up in Abu Dhabi in 1971, where he was appointed minister of state by Sheikh Zayed in the UAE's first government. My father and Mr Pachachi returned to Iraq with the hope of helping the country transition to fully fledged democracy. But they soon realised they were out of their depth.

The Americans viewed Iraq through a sectarian lens. When Paul Bremer, the head of the Coalition Provisional Authority, announced the launch of the Iraqi Governing Council in July 2003, the names of its members were followed by their sect and ethnicity. Mr Pachachi was one of those names. The institutionalisation of ethnic quotas was extremely dangerous. It eroded the idea of a united Iraq and shifted the power balance from the Sunnis to the Shia and Kurds at lightning speed.

The terrible American ideas did not stop there. The Iraqi army and police were dissolved and a vigorous de-Baathification programme was pursued. All this inevitably lead to an eruption of violence on a spectacular scale. The violence overshadowed Iraq's first post-Saddam election in 2005.

It was possible for those of us in exile to vote for the first time. I remember the ballot paper being the size of a tablecloth, full of the names of various parties and coalitions. I had no idea who most of them were or what their agendas were (if they had any). I voted for my father's coalition, the Independent Iraqi Democrats, out of blind loyalty. Many Iraqis voted for parties and coalitions out of blind loyalty by their sect and ethnicity. The Americans had destroyed the institutions of the Iraqi state, forcing Iraqis to return to pre-state tribal and ethnic structures.

I grew increasingly worried about my father. I feared he would be blown up in a car bomb or assassinated. I also feared for his soul. To be involved in Iraqi politics is to be inevitably tainted. Whenever he would call, we would get into arguments about the merits of what he thought he was doing in Iraq.

_______________

Read more:

Fall of Saddam reshaped the Middle East

Fifteen years after Saddam fell, where does Iraq stand now?

Beyond the Headlines Podcast: Saddam Hussein's downfall, 15 years on

________________

All this led me to write my first play, Baghdad Wedding. In the play, Salim, a medical doctor-turned-writer, returns to Iraq post-invasion with the hope of writing about it. Initially an apologist for the invasion, he describes breathing "the intoxicating oxygen of freedom". He even decides to get married in Iraq. His wedding caravan is blown up by an American Apache and he is captured by Iraqi insurgents and then by the American army, who subject him to Abu Ghraib-style humiliation. He is left with a visceral hatred of his country's invaders.

Other characters in the play mock Iraqi politicians for their collaboration with the Americans. By the time the play premiered in London in 2007, Iraq was in the grip of a fierce civil war. The streets were awash with blood. Headless corpses floated down the Tigris. My father returned to London with all his hopes thoroughly dashed. I was grateful that he did not succumb to the greed of other politicians, who shamelessly enriched themselves while the majority of Iraqis wallowed in poverty. Iraq has given us the terms "Green Zone", where the elite live behind security gates and high walls, and "Red Zone", where the rest of the country live in neighbourhoods full of garbage, lacking regular electricity and water and living at the mercy of terrorists and militias.

Regarding the terrorists, George W Bush had announced: “We’ll fight them there so we don’t have to fight them here,” thereby laying bare his country’s complicity in the violence that has gripped Iraq since 2003. My own adopted country of Britain often likes to imagine itself superior to the cowboy Americans. Yet it had committed its own atrocities in Iraq, exemplified by the murder of Baha Mousa.

Several inquiries into the Iraq war have come and gone, the last and most thorough of which was the Chilcot inquiry that lasted for seven years. Despite it being described as "an unprecedented, devastating indictment of how a prime minister was allowed to make decisions by discarding all pretence at cabinet government, subverting the intelligence agencies and making exaggerated claims about threats to Britain's national security", Tony Blair is still at large, often invited by news channels to pontificate on Brexit and other matters. Iraqi novelist Sinan Antoon summed it up best when he wrote: "The invasion of Iraq is often spoken of in the United States as a "blunder" or even a "colossal mistake". It was a crime."

In a short play I wrote called Lost Kingdom, dramatising the interrogation of Saddam after he was captured, the last words the deposed dictator says to George Piro, his Lebanese-American FBI interrogator, are: "You Americans are going to find that it is not so easy governing Iraq." Piro concludes that this was Saddam's curse.

Hassan Abdulrazzak is a London-based playwright of Iraqi origin. His play Love, Bombs and Apples will have its US premiere at the Potrero Stage, San Francisco, on April 19 before touring the UK from May