In 1969, Paul Meyer, a US Air Force mechanic stationed in Britain, took the bizarre and tragic decision to steal a plane.

The aircraft was a four-engine Hercules C-130 transporter, weighing approximately 40 tonnes. He was going it alone, abandoning the usual protocol of having a co-pilot, navigator and engineer. Remarkably, he managed to stay airborne for almost two hours. But somewhere over the English Channel, Meyer crashed. His body was never found.

What on earth could have driven him, totally unqualified, to take to the skies? The answer is simple. He missed his wife.

Meyer was the victim of a universal emotion that many will be feeling during this pandemic: homesickness. Covid-19 has not been kind to families and friends separated by borders, and after a year and a half of varying restrictions, many people, including me, will be hoping that summer 2021 will be one of reunion.

And with that hope comes a borderline obsession with monitoring global travel restrictions. Today my eye was on news outlets in my native Britain, as the UK government revealed the most recent changes to its "traffic light system". I should have been expecting the anti-climax. The government has now taken Portugal off its "green list" – locations where no isolation is mandated on return – in a major blow to airlines and the tourism industry. It is, however, expanding its "red list", areas from which returnees must undergo a hotel quarantine for 10 days, costing almost $2,500.

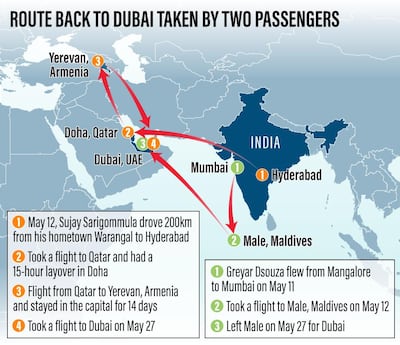

The route I choose to return to the UK from the UAE on leave in August will be relatively boring. In recent days, The National has reported on far more interesting ones. Hundreds of Indian citizens have travelled to Armenia to sit out a two-week quarantine period before they can return to the Emirates, where over 2.5 million other Indians live. Armenians, whose nation includes one of the most widely dispersed diasporas in history and is, therefore, familiar with separation, are now host to a wave of visitors that would not have come if not for the pandemic. Once considered by many of us in the UAE as a weekend getaway, Armenia is now a two-week home for people who, without its hospitality and good prices, would be going nowhere.

And while my route will be confined to Europe, it, too, will be dictated by chance. Italy has opened up a travel corridor with the UAE. Seven EU countries have started using a digital Covid-19 certificate. If I visit friends in France, with some of the strictest controls around, in which EU countries should I wait out the necessary 10 days? I hear Bulgaria is cheap.

Suddenly, the simple European holidays people want every summer are turning into continental tours. Am I concerned about what this could mean for my bank balance? Yes. Am I worried about the wisdom or morality of travelling in a pandemic? Not so much – I, a vaccinated traveller who can stomach (or sinus) PCR tests, would only be going to countries that are open to me. And the more that I think about it, am I worried about having to stop over in Italy, Albania, Cyprus or Bulgaria? Most certainly not. In the 17th and 18th century anyone who was anyone would embark on a Grand Tour of Europe, a trip considered central to a privileged young man's, or occasionally a young woman's, education. I ought to consider myself lucky to be reviving the Classical gap year.

But even apart from that, I will be one of the very luckiest people in search of reunion this summer. We have all dealt with some degree of separation in the pandemic. Mine might be significant in geographical terms, but with healthy friends and family, and the benefit of a vaccine. The mental burden is a very light one.

Separation is not about distance, but rather our ability, or inability, to do anything about it. And when rules mandate distance between families and their sick or elderly relatives, sometimes even in the same towns and cities, fate can seem actively cruel.

The story of mechanic Paul Meyer is back in the news because two British divers claim to have found evidence of a government cover-up after the incident, once again raising questions as to what exactly caused the crash that killed him. But when I read it I found something more than just a remarkable moment in history.

As he flew over the English Channel en route to a home he would never see again, Meyer called his wife. "Honey! I got a bird in the sky and I'm coming home," he said. Minutes later, when the gravity of what he had done started to set in, his triumphalism melted away. "Honey, I'll be really honest with you [...] I feel like the biggest dodo around here right now. Over."

I think my tenuous plans are not enough to make me a dodo just yet. And I certainly have no desire to become the next mechanic Icarus. But would I have had the same reaction to Meyer's story that I did yesterday – even spot a few minuscule parallels – if we were living in a time when we could see the people we miss most? Probably not.

Thomas Helm is a staff opinion writer at The National