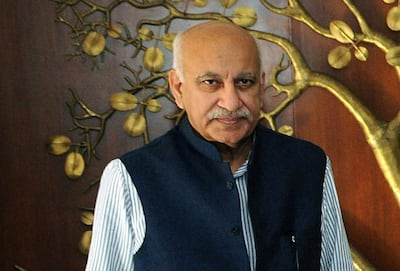

To all appearances, India's #MeToo movement is well on its way. It has its own hashtag, #MeTooIndia. And it has claimed its first high-profile scalp: junior foreign minister MJ Akbar, who resigned after he was accused by more than 20 women of sexual harassment under his previous role as newspaper editor. The women allege that he forced kisses on junior female members of his staff or scheduled meetings with them in hotel rooms while partially clothed. None of the allegations have been proven to date but Mr Akbar said he was stepping down from his post to fight a criminal defamation case to clear his name and is due in court next Wednesday.

#MeTooIndia cases are being meticulously tracked by a leading Indian newspaper detailing every allegation of sexual harassment. The movement can chalk up one early, heartening achievement in the weeks since it properly began: Indian businesses are rushing to make employees more aware of sexual harassment to comply with a five-year-old and hitherto largely ignored law. In fact, many companies are actively imploring female workers to speak out if they suffer something.

All of this speaks to a profound and palpable change in the way Indian women are perceived, as well as their own claim to the right to be treated the way they want. Although the #MeTooIndia movement is limited, as of now, to women of a certain class, it is still a milestone. Until now in India, as in much of south Asia, women were expected to be chaste, to conform to patriarchal norms and to be entirely responsible for their good name and honour.

Indian men were given a pass on their behaviour. For decades, sexual harassment on the streets of Indian cities, big and small, has gone by the frivolous euphemism of "Eve-teasing". That term says a great deal about how India has viewed public sexual harassment, from cat-calls and lewd gestures to groping. It suggests Eve, the temptress, bears responsibility. If men “tease”, it is because Eve provokes it by her clothes or comportment.

Could #MeTooIndia be the point it all starts to change, albeit slowly, unevenly and imperfectly? There is an undeniable heroism in the decision of many Indian women to be loud and insistent about the inappropriate behaviour of male bosses, colleagues and professional contacts from years ago. The historical nature of their revelations means there is little to be gained by going public. In naming and shaming, those women themselves are being named, shamed and blamed on myriad counts, not least for supposed attention-seeking opportunism, extreme puritanism or an undeclared vendetta.

Here’s a disclaimer before I go on. I know, have worked with and am friends with many of the people on both sides of the #MeTooIndia debate. I also count Mr Akbar as a friend; in fact, he has served as a referee for me at various times in my life. As a young journalist in India when Mr Akbar was at the peak of his prominence in the media world, I, too, like many others, heard rumours about his and other editors’ alleged propensity for predatory behaviour.

That was many years ago and that is one of the problems faced by #MeTooIndia. The time lapse between the alleged acts and the reporting of them makes it difficult to foresee a successful resolution to the claims or to conclusively verify the truth of the accused men’s vehement denials. This has raised the question from some quarters – from women as well as men – of the purpose of impugning the reputation of an eminent man, when there is little chance of establishing any wrongdoing. What is the point, they have asked, of making victims of working women who should have dealt with alleged sexual harassment by “speaking up in one voice at the time it occurred”?

That quote, incidentally, comes from a senior, well-respected, female Indian journalist. She decried the allegations against Mr Akbar with the following withering commentary on #MeTooIndia: “By the standards of #MeToo, we will have to stop reading Hemingway, Ghalib, Faiz and Manto. MJ Akbar is flawed. But should we remember him as a sexual predator or an editor with an immense contribution to journalism?"

That, of course, is not the point. No one – including his accusers – is saying Mr Akbar’s work should not be read. #MeTooIndia, like #MeToo everywhere, is about women speaking up for their message to be heard by the next generation – daughters, nieces, little girls. Right now, #MeTooIndia is urban and elitist in being mostly confined to English-speaking workers in high-visibility industries such as the arts, media, music and sport. It does not reach the vast numbers of women in the hinterland, nor the maids, labourers, farmworkers and administration assistants in small grocery stores.

#MeTooIndia does not even speak those other womens’ language. They would call sexual harassment “chedhkhani”, meaning teasing, and rape is often given the euphemistic “izzat lootnah”, or robbing of honour.

To be hashtag-happy does not a revolution make. Even so, it might be the start of one.

Rashmee Roshan Lall is a former editor of the Sunday Times of India