As Lebanon continues to suffer from the pain of an economic collapse, events last week raised the prospect of a worrisome scenario in the country, which the country's political leadership cannot afford to ignore. If they do, what could ensue is a situation ominously reminiscent of the civil war years.

Even before the end of confinement imposed by coronavirus, violent protests had resumed in Lebanon against economic conditions, particularly in the northern city of Tripoli. The Lebanese army was deployed to contain the demonstrators, many of whom had escalated their actions by setting fire to banks. A young protester was killed in one of the melees, while dozens of soldiers were injured.

Two of the main pillars of Lebanon's stability are the banking system and the military. What happened last week underlined that the first is on the verge of a breakdown, threatening Lebanon's finances, while the second is under mounting pressure. Unless there is a rapid injection of dollar liquidity into the banking sector, it will not survive. And unless relief is given to an increasingly impoverished Lebanese society, the army cannot forever be relied upon to curb the protests.

Sunniva Rose: Reminiscing about war years

That is not to say that the military will stage a coup. Rather, as the Lebanese pound loses its value – which has already dramatically eroded the salaries of state employees, including soldiers – the willingness of officers and troops to back the politicians against the people will decline. It is conceivable that if the situation deteriorates further, the military will quietly begin to resist repressing social unrest, insisting that this is the job of the security forces.

If that were to happen, two things could ensue. Protesters, sensing that the tide is turning in their favour, could become even more brazen in their attacks against leading politicians and their interests; and, in response, the politicians could resort to playing on sectarian sensibilities to portray any attack against them as an attack against their religious community. That could push them to resort to autonomous security means to protect their interests, and themselves.

Aya Iskandarani: Test for Hezbollah supporters

Autonomous security is a polite way of saying that sectarian militias could emerge to do what the army is unwilling to do, namely control the streets. With the financial system no longer functioning and the army increasingly failing to protect state officials, the very notion of a state would lose whatever meaning it still has as security institutions are replaced by sectarian armed gangs.

Some politicians would prefer to resist such a development on the grounds that they need the state as a facade for the corrupt oligarchy they have put in place; and to avoid a slide into civil war that would devastate the lucrative edifice they have exploited since the end of the war in 1990. The reality is that while many politicians became prominent during the war years, they are not keen to take Lebanon back to that time, seeing little to gain from it.

Michael Young: Hezbollah and the system

Moreover, Hezbollah, Lebanon's most powerful party, would regard a new civil war as a threatening sideshow to its main task of advancing Iranian interests regionally. That is why some of the party's foes abroad fantasise about a new civil war in Lebanon, believing it would sink Hezbollah in a debilitating conflict, just as the war in 1975 did to the Palestine Liberation Organisation.

With this in mind, Hezbollah and the rest of the political class have accepted a step that they previously would have preferred to avoid. They have asked for assistance from the International Monetary Fund. While their intentions are certainly mercenary, once they are locked into a bailout programme, the politicians' ability to ignore IMF conditions would be relatively limited.

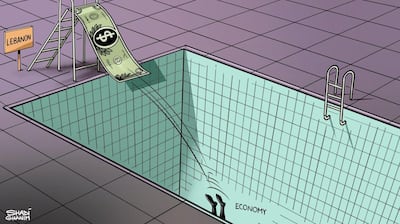

Shadi Ghanim: The currency crisis

That even Hezbollah has accepted the necessity of an IMF bailout, if the fund itself agrees to one, is a testament to the desire of Lebanon’s politicians and parties to salvage what remains of the state. That is why the political class will try to do two things in the weeks and months ahead: save the banking sector, even if it means they have to put their hands on bank deposits; and ensure that the army is spared the worst consequences of widening protests.

In this context, Hezbollah may be in control of the political system, but it is also a system that is rapidly disintegrating. Prime Minister Hassan Diab has made mistakes, is increasingly vulnerable as he has lately alienated influential Maronite and Greek Orthodox representatives, and continues to be challenged by the main Sunni representative, Saad Hariri.

Hassan Diab remains under duress

This suggests that Hezbollah may in the future be tempted to replace Mr Diab’s government with a so-called national unity government, which alone would be able to reach a broad political consensus on an economic plan to address the dire financial situation.

Hezbollah is militarily strong, but today that is hardly enough. The party does not want a new civil war, it seeks an economic revival to assuage an angry population, which only the IMF can provide, and it is willing to make concessions to secure its long-term security. All this will force Hezbollah into making difficult choices in the coming weeks. The party’s domestic rivals will be looking for ways to exploit this to narrow its margin of manoeuvre, while increasing their own.

Michael Young is editor of Diwan, the blog of the Carnegie Middle East programme, in Beirut