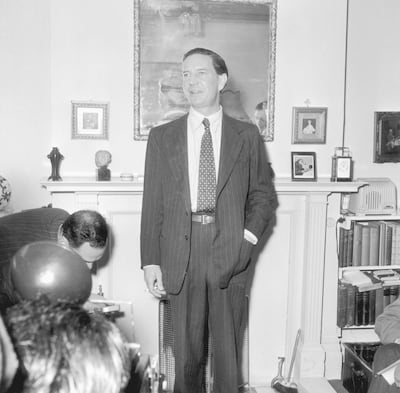

I am putting together a photo essay that asks what remains of the Beirut that Kim Philby once knew. Philby was a senior British intelligence official who was secretly spying for the Soviet Union, and who fled to Moscow from Beirut in January 1963. His betrayal was one of the most significant episodes of the Cold War, and fascinates to this day.

My effort to discover Philby's Beirut really comes from a desire to determine what remains of the city when it was at the height of its appeal during the 1960s. That was when Beirut developed a mythology all of its own, as a cosmopolitan outpost, a playground for the jet set, a laboratory for free ideas and a platform for the clashing ideologies of the region.

It was also, as Philby's experience made clear, an ideal listening post to follow the affairs of the Middle East. He had come to Beirut in 1956 as a journalist, though he still occasionally worked as a spy. After having been accused publicly of being a Soviet agent, before being exonerated by British foreign secretary Harold Macmillan, Philby's friends intervened to have him sent to Lebanon as a correspondent for The Observer and The Economist. Macmillan was wrong about Philby's innocence, but it would take the British many more years to find that out.

Little remains of Philby’s Beirut. As I drove around the city in search of the places in his world – the old British embassy building, his apartment, his bars and restaurants, his father’s tomb – it was demoralising to see how much was falling apart. Philby’s apartment is still there, though the building is empty and decaying. The bars are not, though the ruined buildings that housed two of them remain. And the apartment building of Nicholas Elliott – Philby’s colleague who returned to Beirut to out him – is deteriorating, even if it is about to be renovated.

My permanent arrival in Beirut came only seven years after Philby had flown the coop. Until the end of Lebanon's civil war in 1990, many parts of his city could still be seen – which is why my fascination with his story is really one about the place that I discovered in 1970 and that has been mercilessly erased by Beirut's postwar redevelopment.

When visitors think of Beirut's reconstruction, they tend to focus on the destroyed old city centre that was resurrected after the war. While there was much angry debate about that project, one can make a convincing case for its aesthetic soundness. Yet people forget that much of the rest of the city went through a process of much more hideous construction, as blocs of old and charming neighbourhoods were torn down to be replaced by architecturally inconsequential and soulless high-rises.

Today's Beirut has character, but little else. It is often rundown and severed from much of its past, with only a few crumbling islands acting as a reminder of how charming the city once was. Only money seems to matter, and while money does matter in a city, so too does preserving some aspect of a previous identity. But what is being put up today will have no lingering legacy. Nobody will one day take students on a tour of the more recent buildings to point out an innovation or a bright design idea.

Which is not to say that the Beirut of the 1950s and 1960s – Philby’s city – represents some sort of cultural apogee. But in those days Beirut was much more in harmony with itself. The old houses surrounded by gardens with palm or tangerine trees, like the low-rise buildings with outdoor landings, high roofs and large sun-drenched windows, made much more sense in a city on the Mediterranean.

If a city reflects the character of its inhabitants, Beirut was a less mercenary, more relaxed, more hospitable place than it is today, suffocated by concrete, cars and generator fumes. Even the Mediterranean, which once profoundly defined the city, has instead been contaminated by it. By some remarkable wisdom, Lebanon's political class decided that the best place to deposit the nation's waste was near the seashore.

Lebanese mercantilism thrived in the 1960s, but it was not synonymous with wholesale urban destruction. Today, the warped thinking of the municipal authorities can be summed up in a recent decision to uproot one of Beirut’s rare public parks to build a parking garage. The officials insist the park will be rebuilt over the garage, without explaining how hundreds of trees will be replanted. Nowhere is there any interest in the well-being of Beirutis, let alone ensuring that those who cannot afford a club membership have a space for their children to play.

So, it may sound a bit odd to go on the trail of one of the 20th century’s great traitors to revive a personal nostalgia for the Beirut of the past. But there you have it. In many regards Philby still represents a much more authentic aspect of Beirut’s ambiguous history, its exciting amorality and stimulating shadow games, than what the mundane developers and urban authorities have created today.

Philby’s Beirut was still a city of exciting, if questionable, possibilities – of a double agent who could take to the sea on a rainy night, lying to wife and friends, to escape his past. Now, Beirut is a city that behaves as if it has no past, taking pleasure in its pointless immediateness. That is what happens when daily life unfolds amid buildings and streets signifying nothing.

Michael Young is editor of Diwan, the blog of the Carnegie Middle East programme, in Beirut