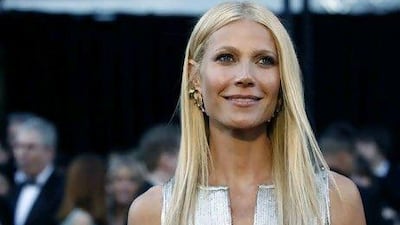

The Hollywood actress Gwyneth Paltrow offered a glimpse into the troubling shift away from evidence and reasoning in the public sphere as she ad-libbed through an interview last week.

Asked about the products sold through her highly profitable commercial venture Goop, Ms Paltrow was unabashed about the apology she was ordered to make for misrepresenting the miraculous healing properties of items made from quartz and jade.

“It was just a verbiage issue,” said the famously grandiloquent actress, who once described her divorce as “consciously uncoupling”.

The Goop phenomenon is one of a long line of ventures, from Paul Newman’s salad dressings to Linda McCartney’s pioneering vegetarian ready meals, that have taken a celebrity name and built around it a successful business.

Goop peddles alternative therapies and other supposedly wholesome offerings. Ms Paltrow defended “ancient healing modalities” that have worked for centuries. When challenged about this by a BBC interviewer, she spoke of the power of the human body to heal itself.

There is more and more of this thinking around. Modern medicine has lengthened life expectancy and reduced disease, but its virtues are now often lost in a rush for more folksy, “natural” remedies.

The British television medic Michael Moseley, for example, made his name promoting the 5:2 Diet, a five-days-off, two-days-on fasting regimen. Now, he is pushing the idea of using placebos − a word that, he pointed out in a recent edition of the BBC TV show Horizon, originates from the Latin for "I shall please".

On the programme, Mr Moseley followed a group of people who took dummy pills for back pain. One man used a wheelchair and was taking morphine to combat his discomfort, yet he ended up walking after taking a new kind of “medication”. These blue-and-white-striped pills were, in fact, made from ground rice. The subject proclaimed a cure, saying: “I got rid of the morphine and kept taking your pills.”

This trial of 117 people took place in the northern English town of Blackpool, a place where one in five of the working-age population has a medical diagnosis of back pain. At the trial’s end, 45 per cent of those taking the placebo pills claimed to have been cured. It is widely documented that placebos have positive effects on those to whom they are prescribed. However, these outcomes are also described as temporary and inconsistent. It is also said that placebos do not help to reverse or arrest the progression of medical conditions.

The one-off claims of televised trials can be easily dismissed, as can slick marketing that puts a modern gloss on the supposedly time-worn properties of crystals and other amulets. But gimmickry is not confined to profitable businesses fronted by entertainers. It extends deep into policy issues.

Last week also saw a great raft of publicity surrounding warnings that climate change can only be stopped if humans drastically slash meat consumption. One expert set a limit of one serving of meat a week to save the planet.

For a variety of reasons, the meat industry is a key contributor to the carbon emissions driving up temperatures across the globe. But headlines suggesting that we should basically give up meat are deeply misguided and counter-productive. Returning farming to its cottage industry roots could, after all, shrink that carbon footprint.

There are many other contributors to the warming of the planet, such as the aviation and ocean shipping industries, non-essential use of cars and all manner of other petrol-fuelled machinery. Then there's the massive environmental impact of the industrial farming of crops such as soya beans and almonds, which are used in meat and dairy substitutes and have respectively contributed to deforestation and droughts.

Many scientists themselves now say that technological solutions will probably be the only means of protecting the earth.

Meanwhile, in recent years, the majority of American states have legalised the medical use of cannabis. Europe is also jumping on the bandwagon, with Britain set to ease restrictions on the sale of cannabis-based medicine and Italy ready to make changes to its laws too.

Driving these legal changes are individual stories of suffering. People seeking to alleviate conditions such as epilepsy via the use of cannabis oil have protested the criminalisation of their needs. Politicians have responded by removing legal barriers, but lack the political will to embrace a framework that harnesses the product for medical advances.

Many plants have health benefits and a large number of highly effective pharmaceuticals are derived from natural sources, but in this instance it is not clear how the best effects are delivered. At present, this plant cannot be properly engineered to treat the specific conditions presented by sufferers, because the science behind it is so fragile.

This is an entirely typical dilemma thrown up by a rush away from best practice in the pursuit of shortcuts. The model of medical progress across the 20th century and into this one has been built on continual scientific breakthroughs by the now widely vilified Big Pharma industry.

It is understandable that people are keen to search for quick solutions that are sympathetic to their experiences. However, in so doing we often forget the basic principles that have underpinned progress. The systematic, scientific approaches that have so effectively tackled disease and suffering, and increased the length and quality of our lives remain our best hopes for the future.