With desperate times, as the saying goes, come desperate measures. Last week, Burkina Faso’s national assembly voted unanimously to allow for the basic military training and arming of citizen vigilante groups. According to the central government, the measure will help defeat the terrorist hydra threatening the very existence of the Burkinabe state.

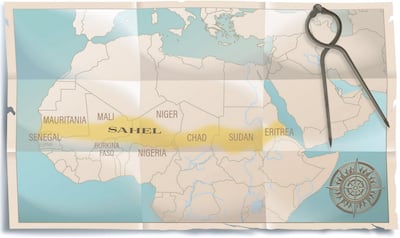

Burkina Faso's descent into militant violence is hard to overstate. According to available data, the landlocked country has faced an eye-popping 7,000 per cent increase in terrorist attacks over the past few years. At the same time, its neighbours Mali and Niger have grappled with 300 and 500 per cent increases, respectively.

This has been a sea change for Burkina Faso, which, for several years, was largely spared from the ravages of the sub-Sahara’s conflict. Only starting in 2015 did militants from northern Mali begin to slip across the large and porous border and commit deadly raids on far-flung Burkinabe border posts. Since then, however, the situation has spiralled: Al Qaeda and ISIS-affiliated militants are running amok, creating ever larger body counts of innocent civilians and government security forces alike.

For its part, the Burkinabe military has proven woefully incapable of addressing the rising tide of brutality. The army is seriously under-funded, suffering from rock-bottom morale and overstretched as it tries to secure increasingly large amounts of its territory from militants. Indeed, recent attacks on border posts near Ivory Coast way down in the country's far south-west underscore that the situation is degrading and that militants might be looking to commit attacks on the far richer states of coastal west Africa, such as Ivory Coast, Ghana, Togo and perhaps even the regional behemoth, Nigeria, which has long grappled with its own militant problems.

Facing a competitive election this year amid growing instability, President Roch Marc Christian Kabore and his political allies are desperate to find ways to stem the violent tide. This explains the perilous measure to arm and fund vigilante groups. And while the civilian militia effort might provide vulnerable civilians some means to protect themselves from rampaging militants, it is also clearly high-risk.

The arming of poorly trained civilians will almost certainly lead to more human rights breaches, such as settling scores between rival ethnic groups. It could also spark friendly-fire incidents, as separating civilian vigilantes and militants during the fog of conflict will be difficult. The consequences will be dire, contributing to further deterioration of the country’s social fabric. Militants seeking to exploit fissures with a view to recruiting disaffected youths to their cause will look upon the situation with glee.

It is also important to remember that security forces and government-backed militias across the sub-Sahara – and elsewhere in Africa – have been accused of countless massacres against unarmed and probably innocent civilians. This has been particularly grave in Mali, where militias aligned with the central government in Bamako have engaged in the unlawful killing of possibly thousands of civilians, often related to inter-ethnic disputes. To make matters worse, these crimes against humanity often go unreported or under-reported, reinforcing a culture of impunity for abusive actors and giving militant groups recruitment fodder from newly alienated ethnic groups. If Ouagadougou were to push ahead with arming more poorly trained people, more massacres and human rights abuses will flow.

Yet as the situation darkens, more risky ideas on the level of arming vigilantes will be considered. Again, the consequences for Burkina Faso and the rest of the region are clear: waves of militant attacks are breaking down the already tenuous hold of central governments. Should this continue to occur, the future collapse of a sub-Saharan state cannot be ruled out.

This is no doubt a worst-case scenario that keeps defence planners in Paris awake at night. In fact, the timing of Burkina Faso's descent into chaos cannot be worse for France, the region's main security guarantor since its 2013 intervention in Mali prevented the collapse of its ally ahead of an alleged impending assault by militants on the capital. This is because the US Department of Defence signalled this month that it might draw down its assets and personnel in West Africa. And while Defence Secretary Mark Esper said in a January 22 briefing to reports that "No decisions have been made", at the same time he underscored that "Mission number one is to compete with Russia and China".

If great-power competition is the pentagon's main focus, then talk of a withdrawal in West Africa is baffling to some in other parts of the US government. Influential Senators Lindsey Graham, a Republican from South Carolina, and Christopher Coons, a Democrat from Delaware, penned a bipartisan letter bashing the idea, stating: "A withdrawal from the continent would embolden both Russia and China" and that "a withdrawal would also abandon our partners and allies in the region". The latter point is a reference not only to West African states, but also to France.

The US military has resources that far exceed those of France. Its support of France’s West African operations include intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance, logistical capabilities and even mid-air refuelling, reportedly at a cost of more than $45 million a year. Consequently, as security worsens across the massive and unstable region, Paris and its African allies will be forced to do even more with less. The White House has cited its frustrations with the slow pace of progress in the sub-Sahara, with one anonymous official telling NBC News this week: “We’re spending hundreds of millions of dollars on a French force that has not been able to turn the tide.”

Complicating matters is the clear rise in anti-French sentiment across the region. This has been felt nowhere more than in Mali, where notable figures such as Salif Keita, a popular singer, have railed against France’s military presence in the country. Keita went so far as to film a Facebook video last year where he advised Malian President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita to stop “subjecting yourself to little Emmanuel Macron – he’s just a kid". This has contributed to the rising phenomenon of “French-bashing”, with protests and the burning of French flags in Bamako sowing dissension between Mr Macron and sub-Saharan leaders.

At the heart of the problem for Burkina Faso, France and other invested countries is the reality that the corrosive government in Mali is the main driving force for much of the region’s ills. Suffering from corruption, predatory elites, mismanagement and a host of other systemic deficiencies, the Malian central government is either unwilling or incapable of taking the hard political action needed to reduce tensions in the country’s restive north. Instead, Bamako has lurched from one reactive policy to the next, supporting renegade militias that commit human rights abuses that fuel more extremism. Consequently, only when France, its neighbours and the international community can effectively lean hard on Bamako to clean up its act and close its massive governance gaps will the situation improve.

Until then, desperate countries such as Burkina Faso will seek desperate measures.

Stephen Rakowski is a sub-Saharan Africa analyst at geopolitical risk consultancy Stratfor, focused on security, political and economic trends across the continent