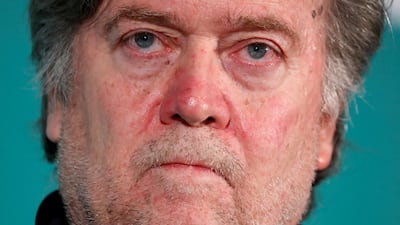

Steve Bannon has moved into top gear in a drive to do for European politics what he did for the ideological centre of gravity in America.

All across the continent, Mr Bannon and his henchmen are wooing allies and laying down structures to assist the rise of a whole new movement.

The US Navy veteran is often described as a nativist. A better term would be a sovereignist. The unifying code of his politics is that countries must act in their own interest with absolute surety.

Not doing so means the disillusionment of the citizenry, a sore that spreads inexorably.

Behind that intense impulse, the policies underpinning Bannonism are not much more than trade and investment protectionism. It is a retreat behind nation state borders.

The challenge to the supranational European Union is obvious. So far only Britain is leaving. Bannonite leaders have taken power but no state has mooted quitting the block just yet.

There is, however, a serious revolt against the German-led policy of absorbing migrants from the Middle East and Africa. So far this development is couched by the Austrian chancellor Sebastian Kurz as necessary to maintain free movement within the EU space. Not a total reversion to national immigration control but an exclusion of outsiders.

In the immediate months ahead, the fate of Brexit Britain is crucial to Mr Bannon's hopes.

The news last week that the recently resigned British foreign secretary, Boris Johnson, had moved back into favourite position for next leader of the Conservative Party represents a great boost to him.

The last senior British politician to pose such a revolutionary threat to the politics of the country was Harold Laski, who was chairman of the Labour Party in the 1940s. When he quit shortly before the party took power in 1945, Clement Attlee sidelined his troubling colleague with a damning warning.

“I can assure you there is widespread resentment in the party at your activities and a period of silence on your part would be welcome,” Attlee declared.

Theresa May had no such scope, nor the rhetorical flair, to take out Mr Johnson with a zinging one-liner.

This is a potential goldmine for Mr Bannon. During his recent trips to London, where he held court in a well-known Mayfair five-star hotel, the tea-drinking Mr Bannon reportedly met the former foreign secretary.

As Mr Johnson moved out of his official grace-and-favour residence in London, he will no doubt have remained confident that he would be back.

Downing Street is still within reach, despite all that has gone before.

There are several scenarios. Mrs May could fail to deliver Brexit and an insurgency within the Conservatives could carry the man who reaches the parts of the country no other Tory can to the pinnacle.

Or the Conservatives could fall out of power as the ultra-Leftist Jeremy Corbyn takes over. His Venezuelan style politics could be impervious to conventional political challenge. The natural alternative would be rabble-rousing Mr Johnson.

For Mr Bannon, the rich pickings ahead lie not just in Britain. That is why he setting up an operations centre-cum-think tank in Brussels at the heart of the continent’s politics. His banner is "the movement". Generating ideas that are taken on country by country would be real proof of the potency of the Bannon mindset.

In the past the hard right has been unsophisticated and relied on rabble-rousing language to mobilise its support. Attempts to try out policy have been bruising. Marine Le Pen, the Front National leader, fell victim to this in the last French presidential election. A complicated but flawed plan to scrap the euro hobbled her efforts to mount a real challenge to Emmanuel Macron from the start.

Viktor Orban, the long-serving leader of Hungary, provides a rather better test bed for Mr Bannon. While his party remains within the mainstream Conservative grouping, Mr Orban is putting flesh on the bones of radical right policies.

Last week he travelled to a gathering of ethnic Hungarians living in Romania and gave an incendiary speech proclaiming his faith in “illiberal democracy”.

Next year’s elections to the European Parliament will be a bellwether for Bannonites. There is talk of common slates involving the hard right parties that have recently entered governments in Italy and Austria. Other triumphant parties are lined up in places like the Czech Republic and Slovenia.

One head-turning Bannonite on the rise is in the Netherlands: Thierry Baudet, the leader of the Forum for Democracy.