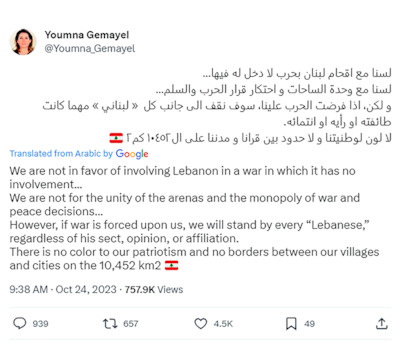

On October 24, a singular tweet was posted on X, formerly known as Twitter. Youmna Gemayel, the daughter of Bashir Gemayel, the late leader of the mainly Christian Lebanese Forces militia and briefly Lebanon’s president-elect in 1982 before he was assassinated, displayed surprising conciliation in remarks she posted.

“We are not in favour of involving Lebanon in a war in which it has no involvement,” Ms Gemayel wrote, in reference to the Gaza conflict. “We are not for the unity of the arenas and the monopoly of decisions on war and peace ... However, if war is forced upon us, we will stand by every ‘Lebanese’, regardless of his sect, opinion, or affiliation.”

Ms Gemayel’s mention of the “unity of the arenas”, or “unity of the fronts”, strategy was a reference to Hezbollah’s alliance with the different groups in the so-called Axis of Resistance, so that Israel would potentially face simultaneous attacks on the Lebanese, Gazan, Syrian and potentially West Bank fronts in the event of a conflict.

Many parties and politicians in Lebanon’s Maronite Christian community, to which Ms Gemayel belongs, have been highly critical of Hezbollah’s efforts to link Lebanon’s fate to that of the Palestinian Hamas and Islamic Jihad, warning that this could lead the country towards destruction in any future war with Israel. The Christians were the principal foes of the Palestinian national movement in Lebanon between 1975 and 1982, and they took up arms against them in a step that contributed to leading the country into its civil war.

Given this legacy, why was Ms Gemayel so keen to affirm a message of unity with Hezbollah, even though she pertinently pointed to the party’s “monopoly of decisions on war and peace”, which has completely sidelined the Lebanese state? Her reasons were unclear, but they reflected a more general tendency in the community to avoid a head-on clash with Hezbollah over a possible spread of the Gaza war to Lebanon.

Even more surprising was the attitude of the current Lebanese Forces leader, Samir Geagea, otherwise a relentless critic of Hezbollah. There was a point a few months ago when Mr Geagea made nearly daily declarations against the party, only for him to remain remarkably subdued after the October 7 Hamas attack. The exception was his interview with the French-language L’Orient-Le Jour last week.

In the interview, the usually forceful Mr Geagea sounded disabused, saying there was little the opposition could do to prevent Lebanon from joining the conflict over Gaza if Hezbollah decided to enter it. Mr Geagea was particularly critical of his main Christian rival, Gebran Bassil, who has been meeting Lebanon’s political forces in order to “protect Lebanon” and “reinforce national unity”, as Mr Bassil has said. Mr Geagea described Mr Bassil as someone with “no credibility and no clear initiative”.

While Mr Bassil’s initiative does indeed lack clarity, again it reflected the desire of a prominent Christian figure to act as national conciliator in the shadow of a possible war. Why this urge among Christian politicians who, whatever their ties with Hezbollah, share a view that Lebanon shouldn’t be part of a “unity of the arenas” scheme?

Mainly, it appears, to avoid a repetition of what happened in 2006. At the time, Hezbollah had emerged from the war with Israel facing an unpredictable mood in its own Shiite community. Shiite villages in the south had been destroyed, as had large neighbourhoods in the southern suburbs of Beirut, Hezbollah’s headquarters. To absorb discontent, Hezbollah had redirected Shiite anger against the government and its own domestic political rivals, many from different sects.

During the period between late 2006 and May 2008, Hezbollah had focused on securing a blocking third in the cabinet of Fouad Al Siniora – meaning a third of ministers plus one. This would have allowed it to control the agenda of a government dominated by its rivals, block legislation Hezbollah opposed, and permitted the party to reverse what had been achieved after Syria’s withdrawal from Lebanon in 2005, which Hezbollah had viewed as a strategic setback.

The refusal of the March 14 majority to accede to this led to a sit-in by the Hezbollah-led opposition, which further heightened sectarian tensions. Ultimately, a government decision in 2008 to prevent Hezbollah from expanding its private communications network led to a short, violent armed conflict, suggesting a return to the civil war years, before a conference sponsored by Qatar imposed a compromise that calmed all sides.

In the event of a new war and Lebanon’s destruction, no political force in the country opposed to Hezbollah wants this to lead to renewed sectarian clashes. If Hezbollah is weakened, all the better, but none of its critics wants to be accused of disloyalty, so that the party can redirect Shiite resentment against them and away from itself.

In this context, Youmna Gemayel’s tweet was especially relevant, as Hezbollah has long condemned Bashir Gemayel as a leader who allied himself with Israel. That she should have implicitly rejected such an accusation by implying that her community would stand with Hezbollah against Israel was significant, even though she has no political position.

The 2006 conflict showed many Lebanese that the aftermath of a war is often far more dangerous than war itself. That certain Christian leaders – in addition to non-Christian politicians, such as the Druze leader Walid Jumblatt – are conscious of this and can take positions that go against their natural instincts, is a sign of their sense of self-interest certainly, but also of maturity in a divided Lebanese society.