Last week, Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga completed 100 days in office. He will hope for hundreds more to follow. But if the proverbial hot seat he currently occupies gets any hotter, it may not be long before he is forced to vacate and make way for someone else.

As of last week, Mr Suga's approval rating – or more precisely, that of his cabinet – has sunk to about 40 per cent. The precipitous fall, from a little over 55 per cent polled just last month, has raised two questions. First, will Mr Suga survive the next year in office? And second, how is it that a politician of Mr Suga's experience and guile is facing such strong political headwinds just three months after being unanimously elected by his party to replace Shinzo Abe?

Mr Suga’s premiership isn't currently in any mortal danger, but his staying power will depend on how quickly he can put out two fires, neither of which is entirely of his own making: a botched coronavirus pandemic strategy and a funding scandal involving the prime minister’s office.

Leading during the Covid-19 pandemic has proved arduous and politically risky for heads of governments across the globe. A once-in-a-century health crisis, which has led to one of the deepest global economic contractions in decades, has already cost a number of world leaders their jobs.

One of them is Donald Trump, the outgoing US president on whose watch more than 330,000 Americans have died. Accusations of Mr Trump's seeming lack of conviction to deal with the outbreak were a contributor to his defeat to Joe Biden in the November general election.

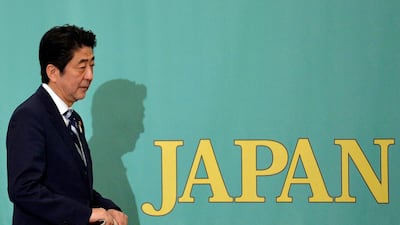

The other leader is Mr Suga's predecessor, Shinzo Abe. Despite serving for a record, uninterrupted seven-and-a-half years, Mr Abe seemed out of his depth in handling the pandemic. His country is much better off than the US in handling the crisis but, amid confusion over whether to prioritise the health crisis or the economic downturn, he was ineffectual in tackling both challenges. Mr Abe resigned in September, citing a personal health issue, but the reality is his disapproval rating had made it untenable for him to stay in power.

Mr Suga’s struggles with the pandemic are similar.

In his previous job as Mr Abe’s right-hand man, he helped unveil the "Go to Travel" campaign, a subsidy programme to encourage domestic travel and tourism as a means to boost the economy. Although it was a good concept, it attracted mostly the retired elderly, who have more time on their hands and a willingness to dip into their life savings. The irony, however, is that it is the retired elderly who have been asked to stay home during the pandemic.

As Prime Minister, Mr Suga continued to promote the campaign while at the same time butting heads with governors of Japan's prefectures over the need to suspend it in parts of the country deemed as coronavirus hotspots. Following a spike in cases across the country, which "Go to Travel" arguably made worse, Mr Suga last week called for the nationwide suspension of the programme between December 28 and January 11. And yet, to the befuddlement of healthcare authorities, he has defied their calls for a national state of emergency.

While Mr Suga’s experience has not paid dividends for him thus far, his years spent in government have come with unwanted baggage.

Last week, Mr Abe faced legal enquiries over unreported political funds, allegedly used to cover dining expenses for his constituents from the Yamaguchi prefecture. Prosecutors allege that upwards of 23 million yen ($223,000) was spent so that these constituents could attend the government's annual cherry blossom-viewing parties in Tokyo between 2015 and 2019. It is a negligible amount of money in the grand scheme of things, but failing to list the expenditure is against the nation's political funding laws.

In the eyes of the opposition, Mr Suga, who was previously Mr Abe's chief cabinet secretary, has been tainted by his long association with Mr Abe and is often reminded of his own very public denial of the funding allegation when it surfaced last year. His presence at dinner parties with celebrities and politicians recently, thereby flouting his own government’s Covid-19 guidelines, caused a great furore, after which he was forced to issue an apology.

Mr Suga is also facing heat over his rejection of six nominees to the Science Council of Japan, a government advisory. A petition criticising his decision has been signed by 140,000 influential members of civil society who claim that the nominees were rejected because they were critics of the government.

None of these controversies are serious enough to bring down Mr Suga’s premiership. Similar allegations have failed to bring down previous governments in Tokyo.

What could hurt Mr Suga, however, is the economic fall-out of the pandemic. Japan’s unemployment rate rose to 3.1 per cent in October, its highest level in three years, and people are worried about their future. Combined with the enduring quality of the funding scandal, further economic contraction could greatly undermine Mr Suga’s power in the hyper-competitive playing field of Japanese politics.

Still, better days could be in store for the country – and possibly for its Prime Minister. The government has signed agreements with four vaccine manufacturers and secured enough doses for the entire population. It has also prepared a detailed timeline, aiming to inoculate all its citizens by the end of June.

The bad news is Japan has one of the lowest levels of vaccine confidence, and a recent poll by public broadcaster NHK reported that up to 36 per cent of the population is unwilling to take the Covid-19 vaccine. The good news is that past experience shows that the Japanese are open to persuasion, particularly if they believe it serves the larger interests of the country. Therein lies an opportunity for Mr Suga.

To get the public on his side, he will need to work on his messaging, which won't be easy. As I previously wrote in these pages, Mr Suga is more backroom dealer than mass leader. But in a time of crisis, he will need to show leadership and be a more effective communicator. It will go a long way in shaping his country's destiny and his own legacy.

If he succeeds, he will have lifted a nation the way Mr Abe did following the 2011 tsunami and Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant tragedies. If he fails, he will end up being little more than a placeholder prime minister until the parliamentary election in October – and one in a long list of Japanese premiers who could not hold onto power for more than a year.

Chitrabhanu Kadalayil is an assistant comment editor at The National