A verdict is expected on Friday at a historic trial of three senior Syrian officials charged with involvement in crimes against humanity and war crimes.

This follows hearings that have highlighted fear among the Syrian community – both abroad and at home – 13 years since the start of the country's civil war.

A glass box with wooden benches reserved for Ali Mamlouk, former head of the National Security Bureau, Jamil Hassan, former Syrian Air Force intelligence director and Abdel Salam Mahmoud, former head of investigations for the service in Damascus, remained empty during the four-day trial.

Their absence has been described as a signal of the continuing impunity in Syria, where at least one of the three men – targeted by international arrest warrants issued by France in 2018 – continues to exercise high-level government duties.

If they are convicted, they could be sentenced to life in prison in France for their role in the death of a father and son of French-Syrian nationality.

“They chose to not send lawyers to this trial. We greatly deplore the fact that have been forced to plead without a defence in front of us,” said lawyer Clemence Bectarte on Friday.

She represents a middle-class Syrian couple in their sixties, Obeida and Hanane Dabbagh, who moved to France decades ago.

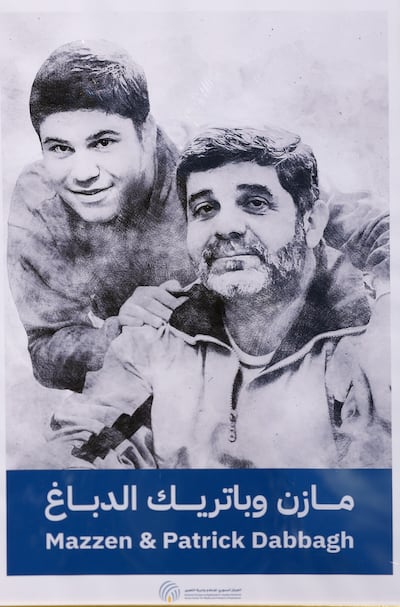

The trial is the result of their seven-year battle for justice for Obeida’s brother Mazzen, a senior education adviser at the local French high school, and his son Patrick, a psychology student. Both were arrested in Damascus in November 2013, in the brutal crackdown following anti-government protests that turned into a civil war.

They were declared dead in detention by the government five years later, as part of a mass release of death certificates under international pressure.

who is bringing the case with her husband, Obeida

Those bringing the case also hope the unprecedented trial draws attention to the systematic use of torture by the Syrian government against its population and stops any normalisation of relations by western countries. This comes as some EU states push to open a debate on a possible return of Syrian refugees.

Dressed in same black dress she wore in 2018 for a Memorial service for Patrick and Mazzen, Hanane Dabbagh told the court on Thursday that she was at first too afraid to join the trial as a civil party with her husband.

But she relented in 2021, as she noticed with growing alarm her husband's deteriorating health due to stress and their increased social isolation as many of their Syrian friends broke off contact, once they knew about the case.

“I thought, I can’t abandon my husband. I fear for my family still in Syria but I am also honoured France gave me this opportunity. I felt ashamed to not do anything. This torture machine must stop.”

Speaking animatedly, sometimes cracking jokes, Hanane's hearing contrasted with her husband’s tired demeanour and low voice.

“If I had lived through what Patrick and Mazzen endured, I would have wanted someone to do the same for me,” said Obeida. “I hope one day, we will be able to go after the head of this regime,” he added, a reference to Syrian President Bashar Al Assad.

Hanane admitted that that her upbeat attitude in court was just a front.

“My children are lucky. They are born here with a father who is an engineer and a mother who is a doctor. But we have suffered to such an extent that it’s not a life any more,” said Hanane.

“I am also here because the hundreds of thousands of Syrians in the world are forgotten today. Leaders like [former US president Barack] Obama and [former French president Francois] Hollande threatened Assad. But he’s still there, and they’re gone.”

Men claiming to work for air force intelligence arrested Patrick, 20, at his family home, before returning for his father Mazzen, 58, the next day. Patrick died a few months after his detention and his father three years later.

The court was told that Mazzen’s wife and daughter were too afraid for the security of their remaining relatives to join the case. They were evicted from their flat, which was then taken over by air force intelligence and occupied by one of the accused, Abdel Salam Mahmoud, according to neighbours.

The prosecution said those acts were “likely to constitute war crimes, extortion and concealment of extortion”.

The court also heard that a relative arrested with Mazzen and released a few days later, thanks to connections with a prominent businessman, had described seeing Patrick with signs of torture, including on his neck.

Another witness, living in Europe under refugee status, also stated to activists that he had seen Patrick in prison a few weeks before his death. But the witness declined to attend the trial, out of fears for his security.

As in thousands of other cases, relatives were never given a reason for Patrick and Mazzen’s arrest and their bodies were not returned.

Since 2011, more than 112,000 people – about 5 per cent of Syria's population – have been arrested or disappeared, according to the Syrian Network for Human Rights.

“I asked someone close to Assad for photos of their bodies. I know it’s not even worth asking for bodies. They said: it’s useless. They’re so disfigured, you won’t even recognise them. It was so hard to grieve,” said Hanane.

Sitting in the audience, Syrians with similar stories told The National they understood why so many fear to join legal proceedings in Europe, recounting how relatives were arrested as a bargaining chip in Syria.

A number of witnesses also told the court on Thursday about the torture they endured in prison.

All except for lawyer Mazen Darwish, who heads the Syrian Centre for Media and Freedom of Expression, that is also party to the case, asked for their full names to not be published out of fear of reprisals against family members in Syria.

“What happened in Patrick and Mazzen is not exceptional. I’m sure that as we speak, people are being disappeared in a similar fashion in Syria,” said Mr Darwish.

Detained for three years in 2011 with a number of other human rights activists, Mr Darwish said he was “lucky” because he did not endure the worst kinds of torture.

This was despite losing 65kg in the first year due to lack of food, overcrowding in his cell and regular beatings that were routine for detainees if they ventured to the toilet.

He also avoided the “German chair” torture, where a prisoner is tied by their hands and feet to a metal chair, which has flexible parts. Torturers bend the back of the chair to cause stretching of the spine and neck, leading to excruciating pain.

“I wasn’t burnt with cigarettes. I wasn’t forced to sit on a flame. They didn’t use electricity on my genitals. I didn’t endure the so-called German chair. I wasn’t placed in a metal coffin for hours. I was only suspended by my hands, not by my feet, and for short periods of time,” said Mr Darwish.

“Many of my colleagues were not as lucky as me.”