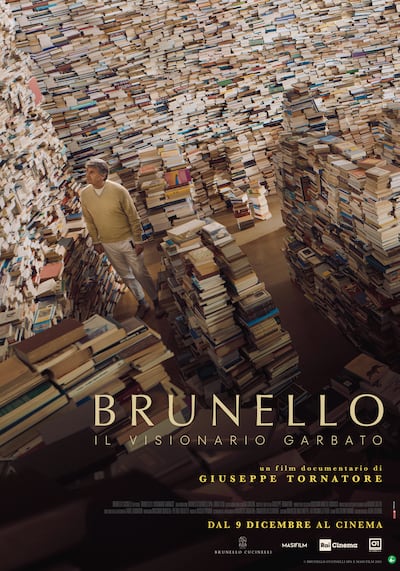

This week, Brunello: The Gracious Visionary arrives in Italian cinemas, screening between Tuesday and Thursday. The film – a telling of designer Brunello Cucinelli's life story – is written and directed by Giuseppe Tornatore, the Oscar-winning filmmaker behind Cinema Paradiso (1988), with music by fellow Academy Award-winner Nicola Piovani. It is an extraordinary alliance – the master of Italian nostalgia turning his lens on one of the titans of the fashion industry.

The film weaves documentary with fictionalised retellings of major moments in Cucinelli’s life. Tornatore describes the project with characteristic lyricism. “It is not quite a documentary, nor a feature film, nor a commercial – but a blend of all three,” he writes in his director’s notes.

“As the narrative unfolds, these two styles do more than simply co-exist: they intersect and occasionally spill into one another, giving rise to a structure that embraces risk and experimentation. In this sense, Brunello: The Gracious Visionary may rightly be described as an experimental film.”

Experimental as it may be, the film is rooted in Italy’s golden era of filmmaking. Besides the Oscar winners behind the camera, the premiere itself took place last week at Rome’s famed Cinecitta Studios. Federico Fellini launched the golden age of Italian cinema here with La Dolce Vita and 8½, while famous Hollywood films such as Ben-Hur and Cleopatra were filmed on the lot.

More recently, HBO’s Rome occupied the sets – and it was on the recreated streets of ancient Rome that we had dinner after the screening. Attending the world premiere made another truth unmistakable: in Italy, as in many countries, fashion is one of the major pillars supporting the creative industries.

While many houses build foundations – Louis Vuitton, Cartier, Prada – Cucinelli has opted for a more holistic vision. His restoration of the medieval hamlet of Solomeo, now the spiritual and operational centre of his company, is as much a cultural project as corporate headquarters. Supporting Italian masters such as Tornatore is simply another extension of that ethos: craftsmanship begetting craftsmanship.

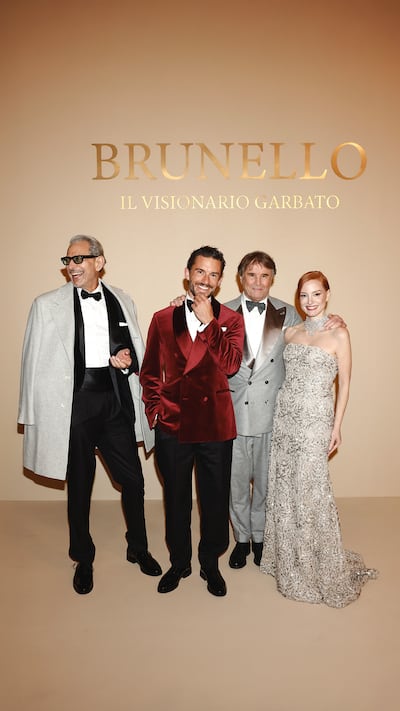

The audience itself reflected the weight of that relationship. Scattered among the global cast of celebrities – Jeff Goldblum, Jessica Chastain, Bassel Khaiat, Ava DuVernay, Jonathan Bailey – sat Italy’s political establishment, including Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni and former prime minister Mario Draghi.

It felt like more than a film premiere; it had the air of a statement about national culture, legacy building and the increasingly cinematic ambitions of contemporary luxury brands.

As for the film itself, amid the re-enactments and interviews with people from Cucinelli’s life – from Oprah Winfrey to his daughters, who are taking a more active role in the business – one figure stood out: actor Saul Nanni. He plays Cucinelli as a young man and is the film’s beating heart.

His performance captures the raw energy of those early, unsettled years – a Cucinelli who was part card shark, part layabout, drifting without a sense of purpose until, in his mid-twenties, he encountered cashmere and, through his wife’s connections, the fashion world that would become his kingdom. Nanni conveys the electricity of discovery: the moment a life snaps into focus.

The documentary elements are polished and persuasive, carried by Cucinelli’s assured relationship with the camera. He is, in many ways, a natural performer – as anyone who saw his theatrical introduction on stage, or the press conference the following morning, will attest. And yet it was the fictionalised sequences that drew me in most powerfully.

They ignite the screen with a different kind of voltage, illuminating the tension between the myth and the man. Perhaps because Nanni’s performance allows for the momentum and vulnerability of youth – a reminder that Cucinelli’s empire was built not on inevitability, but on the ability to capture and shape the moment.

There is precedent, of course, for Tornatore working in this hybrid space. His 2021 film Ennio, a sprawling portrait of Ennio Morricone, blended archive, performance, interviews and cinematic staging to produce something richer than a documentary. Brunello: The Gracious Visionary feels like a continuation of that experiment – another meditation on Italian mastery, and on how artists shape their own legends.

At the press conference the day after the premiere, a characteristically ebullient Cucinelli said he would happily travel anywhere in the world to support the film – a mix of warmth, theatre and self-mythology from a man who has built an empire out of understanding what people want for almost half a century.

Even though the film makes clear that Cucinelli remains involved in every minute decision around his collections, still at age 73, he does seem less interested in the day-to-day business of expanding his empire than in shaping how it will be remembered. And cinema – with its ability to mythologise the everyday, to transform biography into something enduring – may be the most powerful tool he has chosen yet.

FOLLOW TN MAGAZINE