For millennia, the job description for men has been unambiguous: hunter-gatherer, warrior, leader, breadwinner, patriarch. But now the ground is shifting beneath their feet.

None of those roles, it turns out, were created exclusively for men.

As gender disparities in opportunities and pay continue to narrow, women are increasingly demonstrating that anything men can do, they can do just as well, if not better, in addition to fulfilling the “traditional” roles of homemaker, mate and mother.

But as women increasingly find and occupy their true place in the world, so men, it seems, are becoming increasingly untethered from theirs.

In June, Tanveer Ahmed, a psychiatrist in Sydney, Australia, and a regular contributor to The Spectator magazine, wrote about a patient in his late 30s, "recently divorced and working in a middle management role for a major corporation", who attempted suicide after failing to gain a promotion.

The man was convinced he had lost out unfairly to a female candidate because his company operated a gender quota system. It was more than he could bear.

Despair set in, even though, as Ahmed wrote, the man remained in “a well-paid job, is highly qualified and will likely be fine other than having a bruised ego”.

But in men, a bruised ego can prove to be a fatal injury.

Last month, the UK charity Samaritans, which operates a 24-hour support line for anyone with problems ranging from financial worries to suicidal thoughts, gave a cautious welcome to the latest statistics for suicide in the UK, which fell by 5 per cent last year.

But the figures from the Office for National Statistics contained a worrying truth. At 16.6 deaths per 100,000 of population, the suicide rate among men was more than three times that of women.

Though the rate among men dropped fractionally in England in 2016, it increased significantly in Scotland and Wales and hit a record in Northern Ireland of 30.3 deaths per 100,000.

____________________

READ MORE:

Panic attack, acute anxiety disorder - the results are debilitating and frightening

Men’s mental health issues: time to open up and talk about it

UAE experts insist mental health ‘is also a male issue’

Got a case of the Mondays? Sunday is your day to shine

____________________

At first, this doesn’t seem to fit with what is known about depression, which, as a global study published in The Lancet last year concluded, “women are about twice as likely as men to develop” the condition.

But men, dealers in absolutes, seekers of concrete solutions, are more likely to view emotional or psychological problems as “game over” issues, rather than setbacks that can be dealt with.

Male “pride” – in reality, the product of centuries of psychological imprinting that values self-sufficiency above all else – prevents them seeking help either from friends, families or professionals.

As research commissioned by the Samaritans in 2012 concluded, many men judge themselves “against a ‘gold standard’ which prizes power, control and invincibility”.

Men now in mid-life “are part of the ‘buffer’ generation, not sure whether to be like their older, more traditional, strong, silent, austere fathers or like their younger, more progressive, individualistic sons”. And, with the decline of traditional male industries, “these men have lost not only their jobs but also a source of masculine pride and identity”.

It’s not only men in everyday or dead-end jobs who are at risk from mid-life male crises, as the recent deaths of rock musicians Chris Cornell, 52, and Chester Bennington, 41, appear to show.

Cornell, former frontman for the bands Soundgarden and Audioslave, hanged himself in a hotel room after a concert in Detroit in May. He had been taking medication for anxiety. Two months later Bennington, a close friend and the lead singer of Linkin Park, also killed himself, at home in California.

Rich or poor, failure or success, whatever the cause of a collapse of belief in oneself, for far too many men, suicide suggests itself as the only way out. A vanishing sense of worth and identity may be linked to the loss of strong communities and faith, both of which are on the decline in countries such as the UK.

In 2001, the national census revealed that 72 per cent of the population of England and Wales identified themselves as Christian. A decade later this had fallen to 59 per cent with 25 per cent of the population having no religion at all.

Various studies have demonstrated that men in the Muslim world are less likely than those in the West to take their own lives.

Research published in 2011 found that, although exposed to discrimination and other cultural stress factors associated with higher risk of suicide, the rates among Arab-American populations in the United States were much lower than among their Caucasian neighbours.

The researchers, whose work seems to support the idea that immigrants in strange lands should stick together, rather than try to integrate, concluded that “ethnic minorities may be protected against suicide via communally-oriented cultural features, including communalism and a collective social orientation, strong family bonds, affective expressiveness, and positive ethnic group identity”.

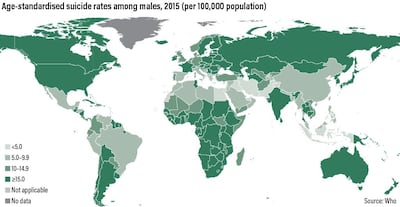

The most recent global suicide statistics from the World Health Organisation, published in 2012, appear to support the idea that men in the Muslim world are generally either less vulnerable to the cultural upheavals destabilising their western counterparts, or are much less likely to turn to suicide.

In the UAE, for example, there were just 274 suicides in 2012, of which the vast majority – 243 – were men. But with 3.9 cases for every 100,000 of population, the rate for male suicide in the UAE, down from a reported 4.3 in 2000, is still well under European levels. In 2012, the rate in the UK was 9.8 for men and there were even higher rates in the Netherlands (11.7), Germany (14.5) and France (19.3). In the US it was 19.4, and in Russia, a startling 35.1.

____________________

READ MORE:

Mental health in the UAE: Three men open up about their battles and how they overcame them

Men are scared to admit they are depressed, mental health experts say

Men tell themselves to ‘man up’ rather than seeking help for mental health issues

____________________

Groundbreaking research carried out in 2011 by the Department of Psychiatry at United Arab Emirates University and counterparts at the University of Vienna painted what remains as the most detailed picture of suicide in the UAE. The research, carried out with the full support of Dubai Police, identified 594 registered suicides in Dubai from 2003 to 2009. Only 10 were among nationals – eight men and two women. Of the 584 expatriates who took their own lives, 543 were men, 41 women. Three out of four expatriate suicides were among Indians.

This gave a rate of just 0.9 for 100,000 people for nationals, and 6.3 for expatriates – almost twice as high as the national rate recorded by WHO.

But there is a caveat to the WHO figures, which are compiled from statistics supplied by individual countries. As WHO notes, “since suicide is a sensitive issue, and even illegal in some countries, it is very likely that it is under-reported [or] misclassified as an accident or another cause of death”.

In the UK, for instance, where suicide was decriminalised in 1961, it is common for coroners to give the benefit of the doubt to ease the pain of relatives and, says the Samaritans, “there continues to be a stigma attached to suicide from a time when it was a criminal offence”.

In Islam, suicide is haram, or forbidden, and the act remains illegal in most Islamic countries, including the UAE.

So are suicides overall, and among men in particular, really that much lower in Muslim communities, or does the stigma of suicide as an act forbidden by faith mean that many deaths are passed off, both officially and within communities, as something else for the sake of the family?

Take the WHO figures for Saudi Arabia, listed in 2012 as the country with the lowest suicide rate in the world – 0.4 cases for every 100,000 people. This rate seems remarkably low even when compared with those of the Kingdom’s neighbouring Islamic states – 3.2 and 4.6 per 100,000, respectively, in the UAE and Qatar.

As the authors of the Dubai study noted, the suicide rate among nationals in the emirate was very low, “which is common for Muslim countries as Islam strictly forbids suicide”. But, they added, previous research has revealed considerably higher rates of undetermined deaths in Muslim than in western countries, suggesting that the culturally unacceptable suicides might be hidden under this category.

But a paper published in the American Journal of Psychiatry in 2004 suggested that the gap between suicide rates in secular and religious countries might be a genuine one, rather than merely a product of under-reporting.

Researchers from the New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University analysed the histories and suicide attempts of 371 depressed psychiatric patients, with and without religion, and found that “religiously affiliated subjects were less likely to have a history of suicide attempts, the best predictor of future suicide or attempts”.

Why? “Traditional religious beliefs mediated the protective effect of religious affiliation against suicidal behaviour”.

Or, as one box ticked in the study’s survey by the majority of religious patients put it, “I believe only God has the right to end a life”.