I hear the boatyard before I see it, a sharp tapping sound wafting through groves of palm trees. Then, strolling towards a clutch of tall and spindly hangar-like shelters, the extent of its almost Heath Robinson-style set-up becomes clear. Men push and pull two-man saws through long wooden planks; others clamber up rickety-looking ladders hooked to struts and members. And looming theatrically over them all is a gracefully curving wooden hull, its keel resting on rudimentary sleepers and propped against timber blocks.

Here at Beypore, on the edge of Kozhikode (formerly called Calicut) in northern Kerala, they’ve been building urus, or dhows, for centuries. This ancient craft derives not merely from the city’s location on the Malabar Coast and access to timber from the nearby Western Ghats, but its former role as a great trading centre. For nearly a millennium, the spice trade powered its prosperity. Merchants and traders came from China, Arabia and North Africa – Ibn Battuta, for example, noted its wealth and cosmopolitan nature – but it was the Portuguese who eventually prised it open to various European powers.

Although a much diminished craft – I’m told that this is one of Kozhikode’s only remaining yards and reputedly one of just five in India – these skilled boat builders still use traditional techniques and tools. Eschewing formal plans or designs, they can easily spend two to three years producing vessels of rare and particular beauty.

The Gulf remains their main market. As I wander beneath hulls where craftsmen tend to joints and caulking with exacting attention to detail, a foreman explains that all three are destined for Qatar, where their luxury, high-tech interiors and engines will eventually be fitted. Launching them is another picturesquely medieval process involving rails, pulleys, cables and ropes, along with old-fashioned brawn. Sadly, I couldn’t linger a few more days to see it for myself.

Kerala’s thriving tourism industry is focused in the south around Kochi and beyond, but now the north is seeing mounting interest. A couple of large resort hotels already have a foothold on its gorgeous, beach-fronted coast and another is set to open in early 2015. Kozhikode’s international connections make it the region’s natural gateway – which is rather how the Portuguese explorer-navigator Vasco da Gama saw it, too, when he landed at the nearby Kappad Beach back in 1498.

It’s no surprise, really, that the memorial to his momentous arrival is so plain and almost hidden away beside a small lane just back from the beach. His arrogance and trivial gifts irked Calicut’s zamorin, or king, and he was immediately seen as a dangerous rival by the city’s long-established Arab merchants. Da Gama’s second visit four years later proved more violent, setting the tone for Portugal’s prickly engagement with the Malabar.

“See up there, damaged roof section,” points Mohammed, my impromptu elderly guide during a fleeting visit to Kozhikode’s Kuttichira. This is the city’s old quarter, which is still largely populated by descendants of wealthy Muslim merchants – the so-called Moplahs – whose ancestry lies in the Arabian Peninsula. Here, at the pale-green, multi-roofed Miskal Palli, one of a clutch of charming old mosques, locals still indicate the faint scars – preserved for posterity – of a Portuguese attack back in the 1500s. Then, as now, the Moplahs lend Kerala’s significant Muslim community a distinct identity.

Heading up the coast, we pause at Kannur, where several beaches, mainly to the south of town, have spawned simple, almost rustic, homestays. What their accommodation lacks in sophistication is – at least for more budget-orientated visitors – made up for in homespun if not earthy charm.

Ours is perched atop a seafront cliff, with an idyllic terrace-cum-dining area overlooking the ocean. Steps plunge straight onto a long beach dotted with fishermen’s’ skiffs. Yet for most of our stay, our young boys prefer another much smaller, almost secret, stretch of low-tide sand framed by coconut palms and part-shielded by jagged rocks.

On the edge of Kannur, we visit St Angelo Fort and its well-tended gardens. This medieval, sea-facing fortress was built in about 1505 by Portugal’s first Indian viceroy, expanded by the Dutch and eventually held by the British until independence. I head on to the nearby Arakkal Museum, a restored section of the former “palace” of the Arakkal dynasty – Kerala’s only Muslim kingdom – which ruled over Kannur and the Lakshadweep Islands. It’s certainly faded and, behind the simple elegance, there probably never was much true grandeur. Yet the mansion helps to underline how even Kerala, one of India’s smaller states, once comprised several different kingdoms and fiefdoms.

The region’s luxury hotels lie farther north, between Nileshwar and Kasaragod. At Neeleshwar Hermitage, the striking, low-slung roof and stout ironwood pillars of its reception building – populated by barefoot staff padding softly on tiled floors – set a genteel, almost contemplative, atmosphere. Sixteen cottages nestle beneath shady palms in lovely gardens right beside an exquisite stretch of empty, golden-sand beach.

“We have this beachside setting,” says Jayan K V, the operations manager, “but we’re not a beach resort.” He isn’t being sniffy. Aside from its winning location and boutique-hotel ambience, Neeleshwar’s reputation is as an ayurvedic retreat. There are five treatment rooms along with a yoga instructor; and most guests embrace one or other when not lounging by the pool or occasionally braving the sea’s notorious currents.

We spent most of our time at Taj Bekal near Kasaragod, one of the Taj group’s Vivanta-branded hotels. As my boys quickly point out, it feels like a “perfect village”, with rooms and villas almost hidden by lush vegetation and extensive gardens. On one side flows the pretty little Kappil River – good for birdwatching or a spot of gentle kayaking – which, in the monsoon season, cuts through the adjoining sandy beach to flow into the sea.

Abhishek Sachdev, a manager at Vivanta, explains the region’s opening to tourism. “Over 15 years back, the Kerala government recognised that areas like Cochin [Kochi] were already very developed. But here the wide open beaches were empty. And Bekal,” he enthused, “is Kerala’s best-kept secret”.

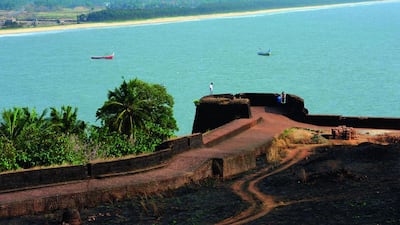

The 17th-century Bekal, Kerala’s largest fort, lies just four kilometres away and one afternoon we set off to visit. Its thick, dark laterite walls remain completely intact and an imposing gateway leads to a now largely empty 16-hectare maidan. We pause by a step-well currently being restored and climb a huge ramp to its muscular observation tower, which was reputedly built by Tipu Sultan, the notorious “Tiger of Mysore”, during his Malabar campaign in the 1780s. It boasts sweeping views both of the complex and up and down the magnificent coastline stretching beyond.

The sturdy walls coax us on a circular walk along the crenellated ramparts, half of which directly overlook the Arabian Sea. We gambol along from one bastion to another and duck through a small gate where stairs dip to a short fortification protruding into the ocean. Its configuration alongside a small separate beach suggests a spot where medieval ships and boats once landed.

It would be all too easy to see little else in Bekal’s hinterland. The Vivanta’s expansive grounds are tranquil, its pool idyllic, the beach almost deserted and there are few utterly compelling reasons to leave. If there’s any disappointment here, it’s the sea itself – strong currents sweeping the steeply shelving beach mean that the hotel urges guests not to swim here at all and it’s obvious that would-be bathers really ought to take care.

Just beyond Kasaragod, Bekal’s nearest town, we drop by a couple of curious temples. Ananthapuram, often simply called the Lake Temple, stands atop a hill in the middle of a water tank seemingly excavated from laterite. Male visitors must enter the temple bare-chested, but the real oddity here is Babiya, the resident crocodile. Most evenings, say the priests, he returns to the main tank, but by day he’s often found at a small nearby pond. I’m sceptical, but we dutifully stroll to his haunt and join a handful of pilgrims, most of us gazing at its murky water and feeling slightly foolish.

We’re about to give up, when a woman implores us to stay, saying that Babiya is about to be fed. “He’s a vegetarian crocodile,” she adds, “and in all these years has never hurt another living thing.” Pacifism, I suppose, had made it sacred. Minutes later, a priest arrives, banging a rice-filled metal pan with a stick and, kneeling by the water, yells “Babiya! Babiya!” as if calling a dog. Then he tips the rice into the pond. Babiya appears momentarily, the boys are thrilled and I’m lost for words at sighting perhaps the world’s only non-carnivorous crocodile.

Once we’d got over its incredible, tongue-twisting name, Srimadanantheshwara Siddhivinayaka – better known (after its location) as the Madhur Temple – presents Hinduism’s more sober face. Built beside the Madhuvahini River and enclosed by a cloistered courtyard, its rounded, three-tiered and partly copper-plated roof is reputedly unique in Kerala. The unusual architectural profile is said to replicate an elephant’s torso – and Ganesh, the elephant god, is the temple’s most popular idol.

Despite signs stating no admittance to non-Hindus, we’re welcomed inside and shown all but the temple’s particularly gloomy yet atmospheric inner sanctum. One smaller shrine caught my eye – by a small cut or groove in its eave, hung a sign saying: “Sword mark left by Tippu.” It’s a reference to Tipu Sultan who, explains a priest, came bent on destroying the complex. No sooner had he struck the first blow when he was overcome by thirst, which he slaked at the temple’s well. Once quenched, he had a miraculous change of heart and the temple was saved. To this day, the well’s water is considered sacred.

The Valiyaparamba backwaters, where a slender 18km-long spit of land shields a lake-like network of waterways and channels, is probably the region’s most picturesque excursion. It’s a beautiful place served by a handful of rudimentary public ferries – the two-hour Ayitty to Kotty route is as good as any, a straightforward relaxing way to see everyday life. The boys marvel at children casually hopping on and off to and from school and home, at locals coming and going from work and shopping or even shinnying up coconut palms. Perhaps this explains Kerala’s undimmed appeal: a place where ordinary life is set amid a profoundly exotic backdrop.

Follow us @TravelNational

Follow us on Facebook for discussions, entertainment, reviews, wellness and news.