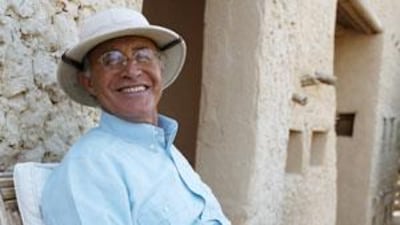

Mounir Neamatalla, founder, Adrere Amellal Desert Ecolodge, Siwa Oasis. I was born in Cairo in 1947. My father was a doctor from Alexandria and my mother came from a prominent Coptic family. I first trained as a chemical engineer, but in 1971 I left Egypt to study environmental science, urban planning and public health at Columbia University, where I earned a PhD. I loved Manhattan, but I am an Egyptian and couldn't imagine not living in my own country, so I returned to establish my company EQI (Environmental Quality International) to work on microfinance and sustainable development projects.

By definition an oasis is a place that hosts desert travellers. Siwa, Egypt's largest oasis, is 300km south-west of the Mediterranean, 500km west of the Nile, and 100km east of the Libyan border on the edge of a vast dune field. It has natural hot springs, salt lakes, vast date palm plantation and ancient ruins, as well as a unique Berber culture and dialect. It was famous in antiquity for the oracle which Alexander the Great consulted in 321BC. On my first trip there in 1996, I had been reading Herodotus: The Histories, and his description of the oasis remains so accurate that on arriving, I had the sense of travelling back in time.

When I first arrived there was only one government rest house and a small hotel built of reinforced concrete. You would arrive in Siwa on the way to Timbuktu, and it was not until after three days had passed that people would ask why was one still hanging around and request compensation. So, despite the lack of infrastructure, a tradition of natural and commercial hospitality already existed. The 13th-century fortress called the Shali was so striking that the idea of restoring a dying architectural heritage through a hotel enterprise seemed evident from the start. Eventually we launched three hotel projects, Albabenshal, an 11-room heritage lodge within the old fortress, Shali Lodge, a budget hotel in the main village of Siwa, and Adrere Amellal, a desert ecolodge.

For 15 years I spent most of my time in Siwa working long hours, taking no holidays. The job stopped me from going to New York and I felt I had lost contact with my favourite place. Now so many New Yorkers come to the oasis that I feel as if I'm living in Manhattan. The thing I dislike here most is the marginalisation of women. There is a noticeable and disturbing absence of Siwi women in public life. A community can't have a renaissance with only half the population.

The construction of the projects employed local artisans using traditional methods, though we brought in structural engineers from Cairo to do the foundations. From the outset we talked with the local community and shared plans, and very quickly any kind of barriers and suspicions were overcome. People that live close to nature have strong instincts and the courage to follow them. We have provided employment to about 600 families and also have crafts, organic agriculture and renewable energy projects. Support from the local community is what makes our initiative successful.

The most famous project, Adrere Amellal Desert Ecolodge, consists of 34 rooms in an isolated spot at the foot of a white mountain on the edge of a salt lake. It's entirely hand-built from mud and rock salt, all the roofs are made from date palms, and the insulation is a mixture of dead olive leaves and mud. We have no electricity and natural ventilation, which means we do without air conditioning. At night we light candles and it's heated with olive wood embers. The management, labour and cuisine are all local.

Many hotels ask people as soon as they arrive what their plans are and offer brochures suggesting things to do. Our guests often wonder why we don't have a reception or any signs or brochures. We want them to explore, to stumble into experience, including the library or the crafts showroom. In terms of time, it's a less effective method of getting to know a place, but the quality of the experience is more powerful. We indicate when we will serve dinner, but we don't have menus, and every night we change the place; guests follow a path of candles. We've created a low key and discreet environment and generally we get people who are sensitive from cultural and ecological standpoints.

My family includes my sisters, nephews and nieces; we have just founded a new company to spread the concept of Siwa elsewhere in Egypt and outside. Siwa has a fragile ecosystem and is at the limit of its development potential in terms of natural resources. We knew from the outset that it should not become a tourism destination where numbers are the measure of success or failure, or which depended on golf courses or extreme landscaping. We are now looking at constructing lodges in Gara Oasis, a small sister oasis to Siwa and at a third oasis area in the Qattara Depression. We would like to do something in Aswan grounded in the Nubian culture and on the southernmost Red Sea coast with the Ababda and Bushariya tribes.

The core concept remains connection with nature and heritage, with local management. Feelings, thoughts, creativity all flow easily, and this is the power of travel, to be connected not just for joy or fun or to get to know each other, but to create a new value system that will bring us together.