Shams El Balad, located at the edge of Amman's Downtown, opened as a small breakfast cafe in 2015. The restaurant, part of a wider business called Shams, was founded by Maha Dahmash and her husband Hazem Malhas.

Over five years, Shams El Balad evolved into an ambitious yet idyllic restaurant that not only promised customers high-quality food and drink, but also positioned sustainability at the core of its business, thanks in large part to the efforts of the couple’s son, Qais Malhas. He joined the team in 2016, and the following year Shams El Balad moved to the rather more grandiose residence next door.

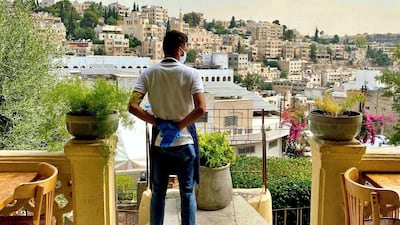

Here was a large outdoor space with white parasols, artistic light installations, ornate tiling, an array of plants and charming waiting staff who demonstrated an understanding of the importance of detail. Sun-drenched days in Jordan would typically have chattering customers tucking into innovative, locally sourced dishes on Shams El Balad’s buzzing terrace.

The delicious menu offered a contemporary twist on traditional dishes, from beetroot falafel and zaatar salad made with tomatoes, white brined Nabulsi cheese, labneh, almonds and tangy spiced sumac, to sweet potato maftoul prepared with raisins, chickpeas and fried almonds.

Shams El Balad reached beyond what the average Amman restaurant was doing, by producing its own sourdough bread, experimenting with home-grown ingredients and delving into the world of fermentation. The business also championed local farmers and sourced organic produce.

Its doors closed two months ago, a direct fallout of the coronavirus pandemic.

“Pre-Covid-19 we had about 60 employees working on all types of things. We had florists, designers, cooks, baristas, bartenders, maintenance personnel. These 60 individuals shaped the experience for our guests in a way that became a constant self-sustaining conversation.

“It was a whole village and that’s one of the hardest things to let go of now, that environment we had,” Malhas says, pausing momentarily as he fights back tears.

A big part of the business’s ethos was to provide a learning environment for staff and to encourage creativity. “We wanted to give staff more than just a pay cheque at the end of the month.”

The restaurateur’s lament

For Malhas, the most crippling aspect of the pandemic has been what he and other restaurant owners describe as a lack of support from the government. “The attitude has been that the business owner wants to rip off the employee and the employee will suffer, but we don’t have that relationship. I went to work, and I worked with my hands. It’s a shared tragedy for us all,” he says.

“There was no support, no way to furlough, you can’t let anyone go. There is a scheme to pay some of the staff wages in place until May, but we are liable to pay this back through social security with 2 per cent interest. We’ve been selling assets to obtain liquidity to pay salaries. And we had the electricity company threatening us every month, so it’s been a constant dance.”

The government may have launched low interest loans for businesses, but the belief within the industry is that few have qualified for these (the Ministry of Tourism was unable to confirm the number). Either way, Malhas says he does not want to spend years paying off a loan for a business that he feels is unsupported.

“It’s as though we’re being punished. When the government announced the temporary closure of restaurants [at the end of August], there was very specific language used to blame us for this sudden spike in numbers,” he says. “It represents the relationship, the animosity, between the public and private sector.”

Having already suffered big losses and amid a further announcement of weekend lockdowns, the final blow came when staff received a notification on the Aman tracing app to say a customer who had been in Shams El Balad had contracted the coronavirus. Malhas says there was no clear government protocol on what to do in this situation. Rather than take any risk, he shut the business down.

Essam Fakhreddin, chief executive of hospitality business Atico Fakhreldin Group, echoes many of Malhas’s concerns. Fakreddin stepped down from the post of president of the Jordan Restaurant Association in May, in protest of the lack of government support. “We were suffering before the crisis, and people are not sitting on big reserves of money unlike what the government thinks,” he says. The closure of Shams El Balad, he adds, was the sad end of a “beautiful project”.

“Eventually the damage will be big – so many people will be unemployed, many businesses will leave the country, there will be bankruptcies. What kind of a message are you sending to young people who are the future of the food industry? The message is that we will not support you.”

Fakhreddin depicts a chaotic approach from the authorities throughout the pandemic. “There was no plan, it’s just been a trial-and-error strategy with last-minute decisions. We need dialogue, we need people from the industry sitting there in the crisis management meetings.”

Nicolas Tsikhlakis, founder of bakery chain Crumz, who worked with the government to establish Covid-19 protocol, said in October the short notice over lockdown decisions made it impossible to plan. “Even now there is confusion within the government regarding what to do if someone has Covid-19 – should the establishment close? The tracking app is slow. The whole thing is not clear.”

Eliana Janineh, the Jordan Restaurant Association’s general manager, also believes there has been “no tangible support for the industry”, and that the government’s decision to reduce tax by half, to 8 per cent for the sector, was something the association had been lobbying for pre-Covid-19. “We’ve also been fighting for the last five years to reduce to cost of electricity, but we are still fighting.

“We found out about the two-week closure of restaurants on television. It was a disaster for businesses and now there’s the closure every Friday until further notice. Weekends account for between 35 and 50 per cent of sales, so imagine the loss,” she says. To make matters worse, Minister of Health Nathir Obeidat said on Saturday that Jordan’s current Friday lockdown policy could continue into 2021.

Janineh confirms the lack of clarity around Covid-19 protocol and says, of the estimated 12,000 food establishments in Jordan, the JRA expects 50 per cent will close. Already about 4,000 restaurants have closed and 6,000 put up for sale since the start of the pandemic.

The government’s counter

In October, members of the tourism industry presented Nayef Al Fayez, the new Minister of Tourism and Antiquities, a report outlining the need for government support in the form of reducing rent and utility fees, and revising loan conditions. Much of the report content echoed the findings of a study into the needs of the sector to recover post-Covid-19, by USAID Building Economic Sustainability Through Tourism Project.

Fayez admits the support measures being offered by the Jordanian government “are not as attractive as what’s being offered in Europe”, but he believes for a country with limited resources Jordan is “heading in the right direction”.

He says that he understands the importance of addressing utility costs. "I was asking for the reduction in tax when I was minister five years ago. Now, my goal is to keep it that way once we've overcome the challenge of the coronavirus," he tells The National.

The ministry is working to address the demands outlined by the sector, but it requires working with other authorities and that takes time, Fayez says. For instance, there was a proposal to shut businesses at 8pm for the curfew, but the ministry was able to extend that to 9pm. It was also successful in securing a one-day weekend lockdown, instead of two days, he says.

“Since being reappointed, I have personally sat with business owners. I’m their voice in the government and I’m trying to keep a balance between what the government has to do and their needs, while trying to convince other authorities to work with us,” he says.

That may offer little hope to places such as Shams El Balad, which have shut shop. "I've given everything I have for four years, non-stop. It is devastating," says Malhas. But for him, he says the silver lining is that "Shams El Balad goes beyond the restaurant and, at this point, beyond Jordan. I have to believe it has the potential to thrive pretty much anywhere."